Remote areas were described as “unused” and/or “underperforming” in a 2017 address by internationally renowned architects Rem Koolhaas and David Gianotten of OMA. Similarly, a 2004 territorial study of Switzerland by ETH Studio Basel, led by architecture firm Herzog & De Meuron, painted the entire country as an urban landscape except for the most remote alpine regions. These were classified as “fallow land” and/or “quiet places”.

It follows that building policies typically centralise decision-making, resources and projects in the largest population centres, irrespective of population distribution or remote community needs. The urban perspective through which building policies are largely determined fails to assess the value of remote regions beyond market-oriented economics.

For remote-dwelling Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people the land, or Country, is entwined with spiritual and cultural identity. It cannot be valued in market terms.

Read more: We won't close the gap if the Commonwealth cuts off Indigenous housing support

A regional approach to building could meet remote community needs and bring about local economic development. It would also reinforce the United Nations-recognised right of Indigenous peoples to maintain cultural connections to Country.

What’s different about remote Indigenous settlement?

Remote Australia cannot be viewed through the same lens as rural Australia. For a start, it has distinct settlement patterns. These are characterised by the presence of large numbers of Indigenous people, a widely dispersed population and, as population geographer John Taylor describes it, a “frequent” and “circular” internal mobility.

While just 1.4 percent of Australia’s population lives in remote areas, 18.4 percent of Indigenous people do. In remote areas, Aboriginal people are more likely to have experienced histories that enabled them to maintain connections to traditional Country. This has resulted in a proportionally greater recognition of Aboriginal land tenure under either the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 or the Native Title Act 1993.

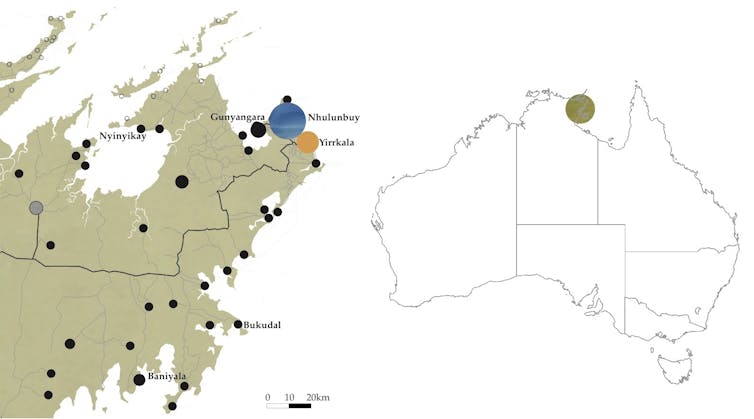

Northeast Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory is typical of this pattern. It is extremely remote and has a largely Indigenous population, with 67 percent identifying as Yolngu.

There are three main settlement types: a largely non-Indigenous mining town of 2,500 people, Nhulunbuy; a mostly Indigenous ex-mission settlement of around 850 people called Yirrkala; and more than 30 homelands across the territory located on traditional family clan lands with populations of up to 150, but typically fewer than 50 people. The people move often from place to place due to seasonal and cultural obligations and/or availability of access to services.

Northeast Arnhem land is extremely remote and has a largely Indigenous population living in three main settlement types. Hannah Robertson, Author provided

Challenges of building remotely

Physical distance and political marginalisation make it difficult and costly to advocate for building in remote regions generally, but Australia’s remote Indigenous regions face further challenges.

Restrictive Aboriginal land tenure limits opportunities for building and/or economic development. For instance, there is no housing market due to the inability to buy and sell recognised Aboriginal land. This means that, unlike in the rest of Australia, buildings do not represent an economic “improvement” to the land.

Furthermore, in Yirrkala, no houses were built in the first five years of the federal government’s Strategic Indigenous Housing Infrastructure Program (SIHIP) – later relabelled the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (NPARIH) and then the National Partnership on Remote Housing (NPRH). This was because others contested Rirratjingu clans’ traditional ownership of parts of the township, which delayed decisions on where houses could be built.

Materials are usually shipped in, but the Delta Reef Gumatj have begun building with locally made timber trusses. Hannah Robertson, Author provided

Economic development and job opportunities are also limited. A special agreement is required to establish an economic venture on Aboriginal land. Obtaining permission is costly and the process slow as extensive legal and anthropological work is required.

The result has been a dearth of local material and construction industries, and jobs, on remote Aboriginal land. Building materials are generally shipped in.

Collectively, these factors contribute to a reliance on government for investment in building. In Northeast Arnhem Land, the Australian or Northern Territory governments provide 95 percent of building funds.

Government-funded housing under construction by DRG, Gunyangara. Hannah Robertson, Author provided

Centralisation model dominates

The policy position of Australian, state and territory governments has long been one of centralisation. Funding is concentrated on the largest population centres where there is a perceived availability of jobs and economies of scale.

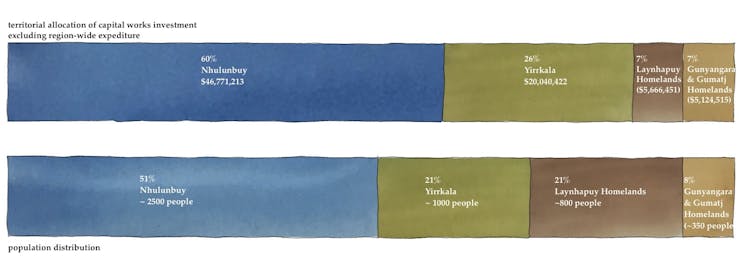

Immediate housing need in Northeast Arnhem Land by number. Hannah Robertson, Author provided

This position is upheld irrespective of identified building needs. For instance, in 2015 Nhulunbuy had 250 vacant houses after the Gove alumina refinery closed. There were shortfalls of 56 houses in Yirrkala and 81 houses across the Laynhapuy homelands. Yet 90 percent of government investment in building was in Nhulunbuy and Yirrkala, despite negligible need in Nhulunbuy and extensive need on the homelands.

The territorial distribution of capital works investment in Northeast Arnhem Land. Hannah Robertson, Author provided

The Northeast Arnhem Land experience aligns with that of other remote Indigenous regions. Homelands, in particular, have been chronically underfunded. After the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was abolished in 2005, state and territory governments largely assumed responsibility for infrastructure and services on homelands without allocating further funds for new housing. The Northern Territory government formalised this position in its Homelands Policy and amendments to it in 2013.

The stage structure at Baniyla Homeland is used as a house due to overcrowding. Hannah Robertson, Author provided

The situation is unlikely to change. If anything, it has intensified. In 2016, threats from the Western Australian government extended from ending new construction to ending basic services to between 100 and 150 of its smallest homelands (more commonly known as outstations in WA).

Read more: Who decides? A question at the heart of meaningful reconciliation

Government building projects in remote Indigenous Australia have not only failed to align with needs but also have limited local economic development. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) Queensland Research Centre reports criticised the alliancing procurement methodology used in the SIHIP/NPARIH program because it allocated risk to the contractor. This knocked small-scale local contractors out of the tender process and resulted in limited use of local labour and materials.

Four steps to better building policy

Policy reforms could stimulate building in remote Indigenous regions. Reforms should focus on increasing local Indigenous input into decision-making. This is critical for identifying and responding to local needs.

From the most difficult to the easiest to enact, reform options could be:

-

alignment with the Uluru Statement from the Heart, treaty or constitutional amendment to give Indigenous people “their rightful place”, as Gough Whitlam put it, at a national level with statutory decision-making authority over their lands

-

amend legislation to devolve decision-making to Indigenous people at a local regional level, as occurred in 2017 amendments to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 devolving these powers from the Northern Land Council to the Tiwi Land Council, Ngarrariyal Aboriginal Corporation and Baniyala Nimbarrki Land Authority, for self-determination of townships on their lands

-

restructure Regional Development Australia agencies to align with recognised territorial regions, as opposed to general population distribution, to foster best building practice and advocacy for local needs

-

do nothing but favour the specification of local suppliers (such as through the Supply Nation network), materials (in Northeast Arnhem Land the Delta Reef Gumatj have begun building with locally made concrete blocks and timber trusses) and labour (through slow builds and the use of semi-skilled technological systems) at a project-by-project level.

Self-funded Delta Reef Gumatj-built single men’s accommodation under construction, Gunyangara. Hannah Robertson, Author provided

Read more: We need to stop innovating in Indigenous housing and get on with Closing the Gap

These policy options are not necessarily mutually exclusive: where practicable they could be conducted in tandem or implemented in part.

The shift to a regional building approach does not require revolutionary change. Rather, it builds upon a remote region’s existing practices, knowledge and organisational systems by decentralising decision-making.

Building is not the panacea for the economic development challenges of remote Indigenous regions – it cannot employ every job seeker. But if building policy decision-making is regionally determined it can better align with community needs and contribute to local industry.

Read more: Indigenous communities are reworking urban planning, but planners need to accept their history

The Conversation is co-publishing articles with Future West (Australian Urbanism), produced by the University of Western Australia’s Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts. These articles look towards the future of urbanism, taking Perth and Western Australia as its reference point, with the latest series focusing on the regions. You can read other articles here.

Hannah Robertson, Innovation Fellow and Lecturer, Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.