The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recently warned that global warming could reach 1.5℃ as early as 2030. The landmark report by leading scientists urged nations to do more to avert an impending crisis.

We have 12 years, the report said, to contain greenhouse gas emissions. This includes serious efforts to reduce transport emissions.

Read more: New UN report outlines 'urgent, transformational' change needed to hold global warming to 1.5°C

In Australia, transport is the third-largest source of greenhouse gases, accounting for around 17 percent of emissions. Passenger cars account for around half of our transport emissions.

The transport sector is also one of the strongest factors in emissions growth in Australia. Emissions from transport have increased nearly 60 percent since 1990 – more than any other sector. Australia is ranked 20th out of 25 of the largest energy-using countries for transport energy efficiency.

Cities around the world have many opportunities to reduce emissions. But this requires renewed thinking and real commitment to change.

Our planet can’t survive our old transport habits

Past (and still current) practices in urban and transport planning are fundamental causes of the transport problems we face today.

Over the past half-century, cities worldwide have grown rapidly, leading to urban sprawl. The result was high demand for motorised transport and, in turn, increased emissions.

The traffic gridlock on roads and motorways was the catalyst for most transport policy responses during that period. The solution prescribed for most cities was to build out of congestion by providing more infrastructure for private vehicles. Limited attention was given to managing travel demand or improving other modes of transport.

Read more: Stuck in traffic: we need a smarter approach to congestion than building more roads

Equating mobility with building more roads nurtured a tendency towards increased motorisation, reinforcing an ever-increasing inclination to expand the road network. The result was a range of unintended adverse environmental, social and economic consequences. Most of these are rooted in the high priority given to private vehicles.

What are the opportunities to change?

The various strategies to move our cities in the right direction can be grouped into four broad categories: avoid, shift, share, and improve. Major policy, behaviour and technology changes are required to make these strategies work.

Avoid strategies aim to slow the growth of travel. They include initiatives to reduce trip lengths, such as high-density and mixed land use developments. Other options decrease private vehicle travel – for example, through car/ride sharing and congestion pricing. And teleworking and e-commerce help people avoid private car trips altogether.

Read more: City-wide trial shows how road use charges can reduce traffic jams

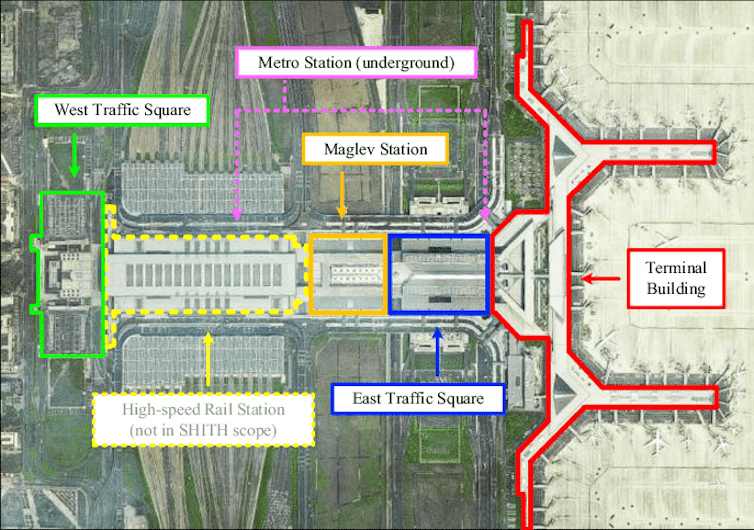

Shanghai’s Hongqiao transport hub is a unique example of an integrated air, rail and mixed land use development. It combines Hongqiao’s airport, metro subway lines, and regional high-speed rail. A low-carbon residential and commercial precinct surrounds the hub.

Layout of Shanghai Hongqiao integrated transport hub. Peng & Shen (2016)/Researchgate, CC BY

Shift strategies encourage travellers to switch from private vehicles to public transport, walking and cycling. This includes improving bus routes and service frequency.

Pricing strategies that discourage private vehicles and encourage other modes of transport can also be effective. Policies that include incentives that make electric vehicles more affordable have been shown to encourage the shift.

Norway is an undisputed world leader in electric vehicle uptake. Nearly a third of all new cars sold in 2017 were a plug-in model. The electric vehicle market share was expected to be as much as 40 percent within a year.

An electric vehicle charging station in the Norwegian capital Oslo. Softulka/Shutterstock

Read more: The new electric vehicle highway is a welcome gear shift, but other countries are still streets ahead

Share strategies affect car ownership. New sharing economy businesses are already moving people, goods and services. Shared mobility, rather than car ownership, is providing city dwellers with a real alternative.

This trend is likely to continue and will pose significant challenges to car ownership models.

Uber claims that its carpooling service in Mumbai saved 936,000 litres of fuel and reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 2,662 metric tonnes within one year. It also reports that UberPool in London achieved a reduction of more than 1.1 million driving kilometres in just six months.

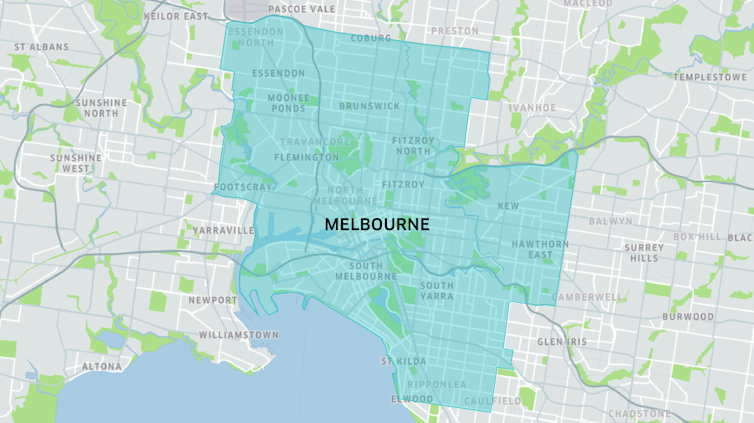

UberPool is available in inner Melbourne suburbs. Trip must begin and end in this area. Uber

UberPool is available in inner Melbourne suburbs. Trip must begin and end in this area. Uber

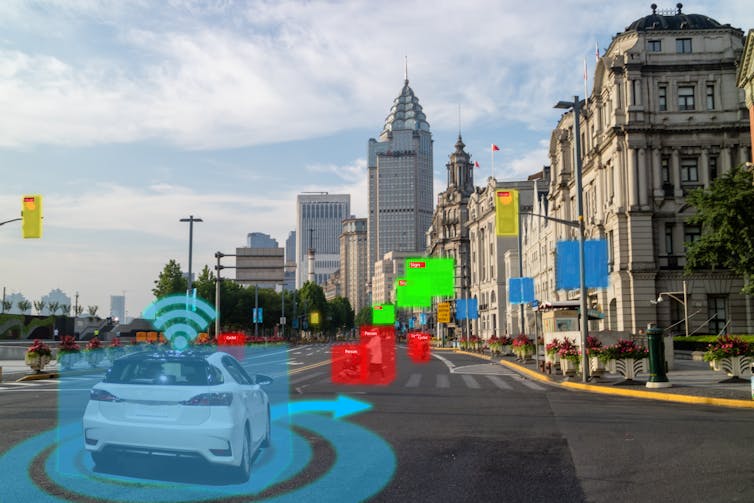

Improve strategies promote the use of technologies to optimise performance of transport modes and intelligent infrastructure. These include intelligent transport systems, urban information technologies and emerging solutions such as autonomous mobility.

Our research shows that sharing 80 percent of autonomous vehicles will reduce net emissions by up to 20 percent. The benefits increase with wider adoption of autonomous shared electric vehicles.

Autonomous vehicles can offer first- and last-kilometre solutions, especially in outer suburbs with limited public transport services. Monopoly919/Shutterstock

Read more: Utopia or nightmare? The answer lies in how we embrace self-driving, electric and shared vehicles

The urgency and benefits of steering our cities towards a path of low-carbon mobility are unmistakable. This was recognised in the past but progress has been slow. Today, the changing context for how we build future cities – smart, healthy and low-carbon – presents new opportunities.

If well planned and implemented, these four interventions will collectively achieve transport emission reduction targets. They will also improve access to the jobs and opportunities that are preconditions for sound economic development in cities around the world.

Hussein Dia, Chair, Department of Civil and Construction Engineering, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.