Road-user charges on electric vehicles based on distance driven were announced in November 2020 by the governments of South Australia and Victoria, while New South Wales ministers have differing views. These charges are justified on several grounds, including the costs of road use and congestion.

Critics argue the new charges will deter uptake of these more environmentally-friendly vehicles. But Australian governments could learn from examples overseas, including New Zealand, where incentives for buyers of electric vehicles more than offset the impacts of road user charges.

Read more: Think taxing electric vehicle use is a backward step? Here's why it's an important policy advance

Road use creates huge costs

One reason for introducing a distance-based charge for electric vehicles is that owners of petrol cars pay fuel excise, currently 42.3 cents per litre. With average fuel use of about 10.8 litres per 100km for Australian cars, drivers pay excise of about 4.6 cents per kilometre for road use. This is much higher than Victoria’s proposed distance charge of 2.5 cents per kilometre for electric vehicles.

The average passenger car in Australia was driven about 11,100km in the year to June 2020 (the pre-COVID average was about 13,000km). This means the federal government collected about A$557 in fuel excise per car.

Although the excise is not specifically dedicated to funding roads, the Australian government is a generous funder of road construction and maintenance. All up, Australia’s three levels of government spent A$28.5 billion on roads in 2018-19. It is reasonable to expect electric vehicle drivers to make some contribution to the roads they use.

The main argument against the new charges is that Australia’s uptake of electric vehicles has been slow and governments should be promoting a shift away from fossil fuels. However, the main disincentive is the cost of buying a new electric car, on par with a luxury car.

Governments could overcome this issue by reducing taxes on electric vehicle purchases and/or providing a subsidy for these purchases, as New Zealand has done since 2016 (with an exemption from distance charges until 2021).

Read more: Transport is letting Australia down in the race to cut emissions

Congested roads demand action

Infrastructure Australia found the economic cost of road congestion in the six largest capitals and their satellite cities was about A$19 billion in 2016. If infrastructure did not keep up with demand, this was likely to increase to A$39 billion a year by 2031.

However, the evidence from Australia and overseas is clear: building more roads does not overcome congestion. The phenomenon of induced demand means new roads simply fill up with more cars making more trips.

Read more: Climate explained: does building and expanding motorways really reduce congestion and emissions?

The emergence on our roads of electric vehicles that don’t generate fuel excise revenue has led to growing calls for road-user charges on these vehicles, including from Infrastructure Partnerships Australia in 2019 and RMIT researchers in November 2020.

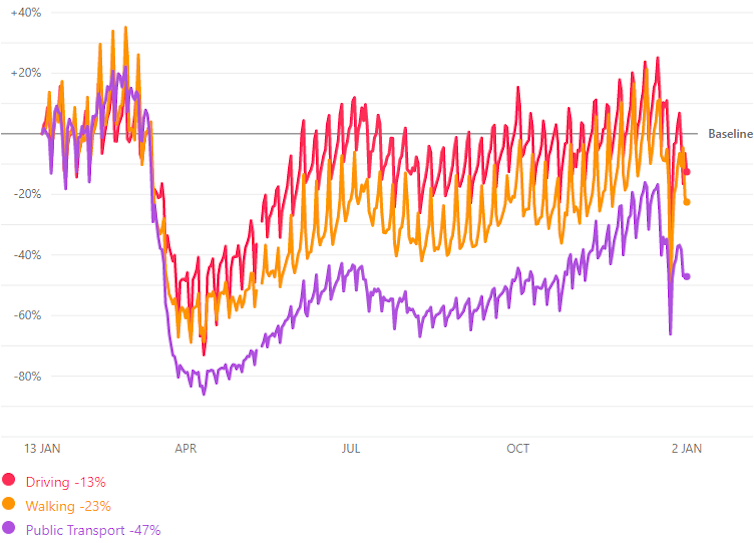

COVID-19 has driven a shift to car use. Before recent outbreaks reduced travel, road traffic in Australian cities was as much as 25% above pre-pandemic volumes.

Australia-wide mobility trends from January 13 2020 to January 2 2021. Apple Mobility Trends

Australia-wide mobility trends from January 13 2020 to January 2 2021. Apple Mobility Trends

Read more: Cars rule as coronavirus shakes up travel trends in our cities

Policy remedies are proven

The proven remedy for road congestion is a combination of better public transport and road congestion charging. This can be a charge to enter a specific area (cordon) or a charge per kilometre. It can be varied by time of day.

In NSW, a ministerial inquiry into sustainable transport proposed such charges back in 2004. A large proportion of submissions in response to a 2002 federal AusLink green paper favoured congestion pricing. Many Conversation articles have also advocated this policy.

In a forward-looking strategy, now open for public consultation, Infrastructure Victoria proposes a review in the next two years of the Melbourne congestion levy on parking, congestion pricing for all new metropolitan freeways and, in the next five years, a trial of full-scale congestion pricing in inner Melbourne.

Singapore has used congestion pricing since 1975 and automated electronic road pricing since 1998.

London, after some controversy, implemented a cordon scheme in 2003. The benefits include reduced traffic, noise and air pollution along with improved public transport. The scheme has been modified over the years and access is now free for electric vehicles and certain hybrids and small cars.

Read more: London congestion charge: what worked, what didn't, what next

Other large cities with congestion pricing include Stockholm and Milan. New York is expected to follow in 2022. A congestion tax is also being considered for Auckland.

Road freight is on the rise too

I discussed road-user charges for heavy trucks in a 2017 Conversation article. At that time in Australia, hidden subsidies for heavy truck use in the form of unrecovered road system costs, along with related external costs of road crashes, pollution, emissions, noise and road congestion, totalled about A$3 billion a year. I now estimate this shortfall to be about A$4 billion.

Read more: Trucks are destroying our roads and not picking up the repair cost

Australia should introduce mass distance pricing as has been used in New Zealand since 1978 and increasingly in Europe. Instead it relies on annual registration fees and a discounted heavy vehicle fuel excise of 25.8 cents per litre. These charges have essentially been frozen for five years.

Proposals for a modest 2.5% increase in the heavy vehicle fuel charge were shelved after COVID-19 hit. They are now under review again.

One in three submissions to a federal inquiry into developing a National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy highlighted the need for road pricing. The final 2019 strategy all but ignored this issue, despite a projected near-doubling of road freight by 2040.

Failure to reform road pricing coupled with ongoing relaxation of mass and dimension limits for heavy trucks is a recipe for ever more “loads on roads” at the expense of rail freight and coastal shipping.

In 2002, the then Treasury secretary, Ken Henry, said of the projected increases in city traffic and interstate road freight: “Not dealing with these issues now amounts to passing a very challenging set of problems to future generations.”

In 2010, the Henry Tax Review made several road-pricing recommendations. These included that Australian governments “should accelerate the development of mass-distance-location pricing for heavy vehicles”.

The review also recommended governments analyse the network-wide benefits and costs of introducing variable congestion pricing on tolled roads and consider extending it across heavily congested parts of the road network.

Road pricing reform is now long overdue. And it should include electric vehicles.

Philip Laird, Honorary Principal Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.