Outright home ownership has long been regarded as a supporting pillar of Australian retirement incomes policies. A report released today by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) raises concerns that rising mortgage debt and falling home ownership rates in later life are undermining the role of home ownership in supporting retirees’ financial wellbeing.

Achieving outright home ownership is similar to the accumulation of pension income entitlements that come on stream in later life. This is because the outright owner does not have to meet rents. That reduces the need for a large income stream to pay for shelter as well as the chances of low-income older Australians falling into poverty.

Read more: Why secure and affordable housing is an increasing worry for age pensioners

Numbers of mortgagors and private renters soar

According to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Survey of Income and Housing, home-ownership rates among Australians aged 55-64 years dropped from 86 percent to 81 percent between 2001 and 2016. We are also seeing a major shift in older Australians’ readiness to shoulder mortgage debt in later life.

Mortgage burdens have spiked in the 55-64 age group. In 2001 roughly 80 percent were mortgage-free. Fifteen years later this had plummeted to only 56 percent.

Indebtedness is even growing among owners aged 65 and over. In 2001 nearly 96 percent were mortgage-free. By 2016 this proportion had fallen below 90 percent.

These trends are expected to continue. That means, as the population ages, a growing number of older Australians will still be paying off mortgages, or trying to meet rents from fixed incomes.

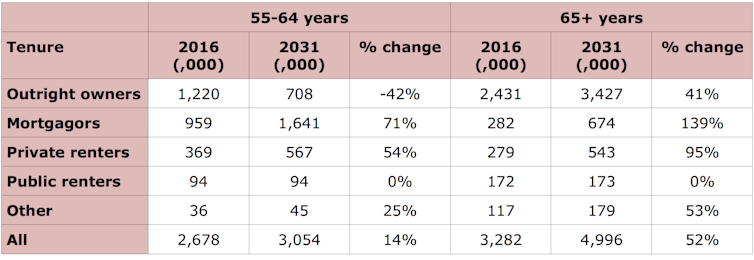

The table below shows how the housing tenures of older Australians are projected to change between 2016 and 2031 based on ABS population forecasts and modelling estimates.

Projected changes in housing tenures of older Australians between 2016 and 2031. Authors’ calculations from HILDA Survey and ABS population projections, Author provided

Projected changes in housing tenures of older Australians between 2016 and 2031. Authors’ calculations from HILDA Survey and ABS population projections, Author provided

We expect the number of outright owners aged 55-64 to plunge by 42 percent, from more than 1.2 million to 708,000. The number of 65-plus outright owners is predicted to rise by 41 percent, but this lags behind the 52 percent population growth in this age group.

On the other hand, the numbers of older mortgagors and private renters are projected to soar. Among 55-to-64-year-olds, mortgagor numbers jump from under 1 million to over 1.6 million, a 71 percent increase. The number of private renters rises by 54 percent from 369,000 to 567,000.

Beyond what was the age pension threshold of 65 years, mortgagors and private renters are expected to roughly double in number.

Read more: More people are retiring with high mortgage debts. The implications are huge

What are the budget impacts?

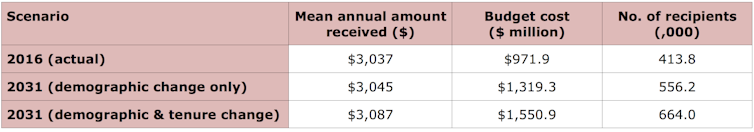

The combined impact of these changes in tenure and demographics is expected to increase Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) eligibility among seniors.

On its own, demographic change is forecast to lift the number of CRA recipients, and the real cost of providing CRA, by around 35 percent.

Add the projected increases in the private rental share of the housing stock and the number of CRA recipients is estimated to rise by 60 percent, from 414,000 to 664,000, between 2016 and 2031.

The real cost to the federal budget of rent assistance payments to older Australians is forecast to blow out from $972 million to $1.55 billion a year.

Actual 2016 and projected 2031 tenure shares and population counts among Australians aged 55+ years. Authors’ calculations from HILDA Survey and ABS population projections, Author provided

Actual 2016 and projected 2031 tenure shares and population counts among Australians aged 55+ years. Authors’ calculations from HILDA Survey and ABS population projections, Author provided

We can also expect to see public housing waiting lists grow if these tenure changes and demographics eventuate. Their combined impact through to 2031 is expected to swell the number of older persons eligible for public housing from 247,000 to 441,000 – a 79 percent increase.

What are the impacts on poverty?

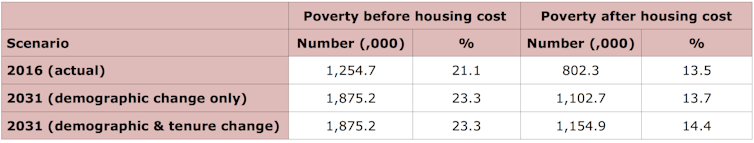

On an income-only basis we estimate 1.25 million seniors were in poverty in 2016. On taking their housing costs into account, that number falls to 802,000.

But the role of home ownership in preventing poverty is challenged if our projected declines in home ownership rates and increases in debt eventuate. The table below shows the projected increase in the after-housing-cost poverty count from 802,000 in 2016 to 1.15 million in 2031.

Actual 2016 and projected 2031 poverty counts on a before- and after-housing-cost basis among Australians aged 55+ years. Authors’ calculations from HILDA Survey and ABS population projections, Author provided

Actual 2016 and projected 2031 poverty counts on a before- and after-housing-cost basis among Australians aged 55+ years. Authors’ calculations from HILDA Survey and ABS population projections, Author provided

Policy challenges on multiple fronts

The demand for public housing will grow. If all else remains unchanged in the housing system and economy, seniors on public housing wait lists will increase by over 75 percent. That’s more than twice the 35 percent increase in the population of seniors between 2016 and 2031.

Community housing organisations would also come under increasing pressure.

As the number of senior private rental tenants grows, governments will need to reform tenancy regulations in ways that enable housing retrofits to meet mobility needs and allow for ageing in place. Tenure insecurity in the rental sector could hinder planning for aged support services.

Read more: Life as an older renter, and what it tells us about the urgent need for tenancy reform

We may also see a more fundamental transformation of Australia’s housing system and lifestyles in old age. High real house price growth relative to incomes remains a barrier to first home ownership despite low interest rates. Furthermore, the mandatory superannuation guarantee likely displaces some saving in other assets, including housing.

There is therefore a growing prospect of delayed entry into home ownership and of people carrying more debt in later life. Longer working lives and the use of superannuation benefits to pay down mortgages both look increasingly likely.

Rachel Ong ViforJ, Professor of Economics, School of Economics, Finance and Property, Curtin University; Gavin Wood, Emeritus Professor of Housing and Housing Studies, RMIT University; Melek Cigdem-Bayram, Research Fellow, RMIT University, and Silvia Salazar, Research fellow, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.