The Sydney Opera House celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. This Australian icon was, of course, designed by Danish architect Jørn Utzon, as a result of an international design competition held at a time when many Australians still looked to the northern hemisphere for stylistic guidance and direction; a time when we imported European or American culture.

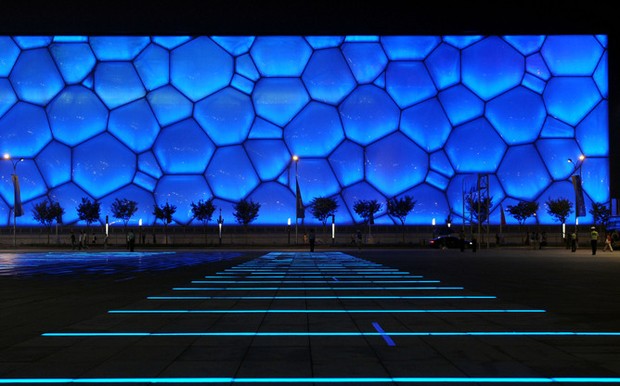

Some 40 years on, we are now exporting culture and Australian architects are designing iconic buildings in other parts of the world, such as the 2012 London Olympic Park and Stadium, and the Beijing National Aquatics Centre (the Water Cube).

Is there a unique Australian architectural 'style'? If so, where did it come from?

A backwards glance

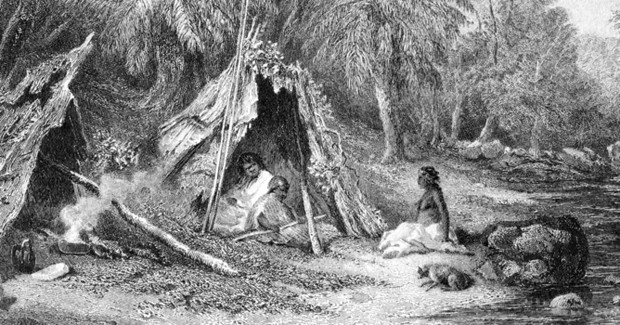

In 1788, when British settlers first started arriving in Australia, vernacular Australian architecture (based on localised needs and construction materials) consisted of nomadic shelters, designed and built by indigenous Australians.

Wikimedia Commons

Due to the significant numbers of architects who subsequently moved from England to Australia to join the British colonies, 19th-century Australian architecture quickly changed to be largely Eurocentric in focus.

Melbourne’s Royal Exhibition building, built between 1878 and 1880. AAP Image/Museum Victoria

During the 20th century, however, buildings started to adapt to respond to Australia’s unique climatic conditions, which offer year-round access to the outdoors. The influence of America saw families seeking to own freestanding houses with backyards, to satisfy their increasing desire to fulfil the “Australian Dream”.

In the late 20th century, as Australia started to become more multicultural, derivative designs began to be replaced with imported exotic styles, especially those of South-East Asian influence. Freestanding houses started to be replaced with semi-detached and high density housing, as urban precincts started to develop.

Challenge accepted

Australian architects are now responding to the unprecedented 21st-century challenges of population growth, preservation of the environment and the threats of climate change.

As architects continue to shape urban precincts and their supporting infrastructure, the design of public space has now importantly changed focus to preserving the quality of both the built and natural environments. The sensitive relationship between buildings and the Australian landscape that hosts them is of critical importance, and something for which we are becoming internationally recognised.

While much of the industrialised world has been in recession for the past few years, Australia’s economy has grown, as have neighbouring Asian economies.

China’s National Aquatics Centre, also known as the ‘Water Cube’, was designed by Australian architects. AAP Image/Dean Lewins

Currently, Australia has seven of the largest 100 architecture practices in the world: Woods Bagot, Hassell, Cox Architecture, HBO + EMTB, GHD, Hames Sharley, and Thomson Adsett Architects.

For most of these large practices, income from international projects is actually more than the income generated by domestic projects. Across the whole architectural sector the figure for international income is nearer to 10%, but it is clear that we are now exporting much of our talent, skill and cultural expertise rather than importing it.

The architectural Oscars

So how does Australia compare, architecturally, with the rest of the world? How have we fared in international awards, prizes and festivals such as the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, the World Architecture Festival, and the Venice Architecture Biennale?

There is just one Pritzker Architecture Prize awarded annually to:

honour a living architect/s whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.

Magney House at Bingie Bingie on the NSW South Coast, designed by Australian architect Glenn Murcutt. AAP Image/Anthony Browell

There has been one Australian recipient of the Pritzker prize in its 35-year existence: Glenn Murcutt AO in 2002. His award was based on a career that focused largely on designing houses that responded directly to unique Australian conditions.

Indeed, the period of Murcutt’s foundational work in the latter part of last century coincided with growing international recognition of Australian architecture.

Glenn Murcutt grew up in Papua New Guinea, where he developed an appreciation for simple vernacular architecture and a relationship with nature. He practised sustainability long before it became an architectural buzzword. His design philosophy, “touch the earth lightly”, motivates him to design in response to environmental factors, using locally-sourced materials and to sensitively fit into the Australian landscape.

Mary Short House in Kempsey, NSW, designed by Australian architect Glenn Murcutt, whose motto is “touch the earth lightly”. AAP Image/Glenn Murcutt

This sensitive attitude to the environment and our tin and timber tradition – a history of functional sheds and beach houses – gained Australia international attention.

Now Australian architects are bringing that same sensitive attitude to larger projects in many parts of the world.

International attention

The World Architecture Festival is an annual program of awards, jury critiques, and international speakers, all celebrating the best architecture of the past year. It was first held in 2008 in Barcelona but for the past two years has been in Singapore.

This annual get-together brings more than 2,000 architects from all over the globe, and exhibits short-listed projects from more than 40 nations to compete for awards in 16 built project categories and 11 future project categories.

In 2013, Australian architects achieved unprecedented levels of success in the World Architecture Festival awards program, winning the categories of Culture, House, Transport, Future Infrastructure and Competition Entries.

Toi o Tamaki in Auckland, New Zealand won the 2012 RIBA International Award for architectural excellence and the 2013 World Architecture Festival Building of the Year Award. AAP Image/Supplied by the Royal Institute of British Architects

Australian architects also won three of the highest awards. It is also worth noting that two of the three winning projects are outside of Australia:

-

World building of the year: Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tamaki, New Zealand by Francis-Jones Morehen Thorpe with New Zealand architects Archimedia.

-

Future project of the year: the National Maritime Museum of China, by Cox Architecture

-

Landscape category: The Australian Garden, Australia, by Taylor Cullity Lethlean and Paul Thompson.

Of the Landscape category winner, the judges noted that the project “stood out with its originality and strong evocation of Australian identity”.

The Australian Garden, Australia, by Taylor Cullity Lethlean and Paul Thompson. AAP Image/Supplied

Of the House category winner, a delightful little timber home in Brisbane, they noted “a realness and authenticity to the spirit of the house”.

It seems, then, that there is definitely an identifiable Australian design identity, something for which we can be recognised and rewarded.

Australian architecture has also been recognised at the Venice Architecture Biennale. The Biennale is a showcase of cutting-edge contemporary architecture and architectural thinking, through the exhibitions by invited architects, and through the self-curated national pavilions.

Entrance to the Australian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Dr. Philip Crowther

Australia is one of only 30 nations to exhibit in its own pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. We have done so in a temporary pavilion since 1988, but a new permanent pavilion has been designed by Australian firm Denton Corker Marshall and will be built soon. The pavilion typically attracts around 90,000 visitors during the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Interior of the Australian Pavilion at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale. Dr. Philip Crowther

Facade of the Australian Pavilion at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale. Dr. Philip Crowther

Global shifts

Perhaps our rough-and-tumble early colonial heritage has served us well in developing a resilient approach to the rapidly changing global environment.

Free of the European notion of heritage and the constraints of ancient cities filled with historic buildings, we have engaged with a greater diversity of perspectives, from Australia’s 40,000 year indigenous history, through a sensitivity to the environment, to the realisation that we are part of a 21st-century Asia.

We are no longer operating on the distant fringes of Europe or America, but now firmly at the centre of a global shift in both economic and cultural perspectives.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.