In 1955, an enormous photographic exhibition, The Family of Man, challenged the world as to what it meant to be human. The curator, Edward Steichen, assembled 503 photographs by 273 photographers from 68 countries, while his brother-in-law, the poet Carl Sandburg, provided the lyrical subtext to the show and its title.

In his poem, The Long Shadow of Lincoln: A Litany (1944), Sandburg wrote, “There is dust alive/ With dreams of the Republic,/ With dreams of the family of man/ Flung wide on a shrinking globe”.

Taloi Havini & Stuart Miller Sami and the Panguna mine 2009–10, 80.1 × 119.9 cm, type C photograph National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased, Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2014 © Taloi Havini and Stuart Miller

Taloi Havini & Stuart Miller Sami and the Panguna mine 2009–10, 80.1 × 119.9 cm, type C photograph National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased, Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2014 © Taloi Havini and Stuart Miller

In some ways, this new vast exhibition, Civilization: The Way We Live Now, a version of which has just opened at the National Gallery of Victoria, catches the flame of the challenge of The Family of Man with its dreams of humankind living on a rapidly shrinking globe.

The show brings together over 100 contemporary photographers from Africa, Asia, the Americas, Europe and Australia with over 200 photographs. Unlike its illustrious predecessor of more than 60 years earlier, many of the photographs in this exhibition are huge in dimensions and in a very wide range of mediums.

Massimo Vitali, Italian born 1944, Piscinao de Ramos 2012, Lightjet print. 232.5 x 185.5 x 6.0 cm. © Massimo Vital

Massimo Vitali, Italian born 1944, Piscinao de Ramos 2012, Lightjet print. 232.5 x 185.5 x 6.0 cm. © Massimo Vital

“Civilization”, the title of numerous exhibitions, conjures the image of civilisations of the past – Egypt, Rome, Byzantium – empires that rose and collapsed. This exhibition explores the concept of a “planetary civilisation” – one, where for the first time in human history, more people live in cities, than in rural settings.

Reiner Riedler, Austrian born 1968, Wild River, Florida 2005 from Fake Holidays series type C photograph. 100.0 x 120.0 x 4.0 cm. © Reiner Riedler

Reiner Riedler, Austrian born 1968, Wild River, Florida 2005 from Fake Holidays series type C photograph. 100.0 x 120.0 x 4.0 cm. © Reiner Riedler

Human mobility and interconnectivity have meant that more people, countries and economies are interdependent than ever before. For the first time, there is a real prospect that the human species stands to comprehensively annihilate itself, not through an act of war, but through man-made climate change and over consumption. It is also the first time that photographers are virtually everywhere and are photographing virtually everything.

Gjorgji Lichovski, Macedonian born 1964, Macedonian police clash with refugees at blocked border 2015, type C photograph. 70.7 x 104.0 x 3.5 cm. © epa european pressphoto agency / Georgi Licovski

Gjorgji Lichovski, Macedonian born 1964, Macedonian police clash with refugees at blocked border 2015, type C photograph. 70.7 x 104.0 x 3.5 cm. © epa european pressphoto agency / Georgi Licovski

The curators of this exhibition, William A. Ewing and Holly Roussell, have examined many thousands of contemporary photographs and have spoken to hundreds of photographers around the world.

Through this process of interrogation, the material has suggested eight fluid, porous sections around which the exhibition is arranged: Hive, Alone together, Flow, Persuasion, Control, Rapture, Escape and Next. These, as Ewing stresses, are some of the broad themes that are preoccupying many of the world’s finest photographers today.

Priscilla Briggs. American born 1966 Happy (Golden Resources Mall, Beijing), from the series Fortune 2008 type C photograph 100.0 x 128.0 x 4.5 cm © Priscilla Briggs

Priscilla Briggs. American born 1966 Happy (Golden Resources Mall, Beijing), from the series Fortune 2008 type C photograph 100.0 x 128.0 x 4.5 cm © Priscilla Briggs

Last year, the exhibition was shown in Seoul, earlier this year in Beijing and now it is in Melbourne, where it has been considerably trimmed of some of its international content and supplemented by a number of Australian photographers.

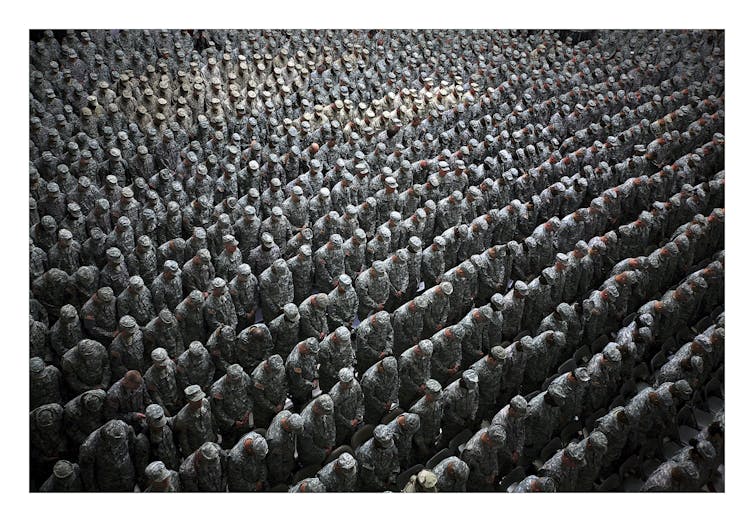

Ashley Gilbertson, 1,215 American soldiers, airmen, marines and sailors pray before a pledge of enlistment on July 4, 2008, at a massive re-enlistment ceremony at one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces in Baghdad, Iraq 2008, from Whiskey Tango Foxtrot series, type C photograph 69.0 x 94.0 x 5.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Ashley Gilbertson / VII Network

Ashley Gilbertson, 1,215 American soldiers, airmen, marines and sailors pray before a pledge of enlistment on July 4, 2008, at a massive re-enlistment ceremony at one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces in Baghdad, Iraq 2008, from Whiskey Tango Foxtrot series, type C photograph 69.0 x 94.0 x 5.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Ashley Gilbertson / VII Network

Next year, the exhibition will travel to Auckland, in 2021 to Marseilles and there is promise of future venues in the coming years. The Family of Man was to tour for eight years and attracted over nine million visitors and there is every possibility that this exhibition will match or exceed this number.

‘Homogenising humanity’

If The Family of Man posed the question what do humans have in common to make them human, photographs in Civilization focus on what the curators term the “shared human experience”. The historian Niall Ferguson noted in his book Civilization: The West and the Rest (2011): “It is one of the greatest paradoxes of modern history that a system designed to offer infinite choice to the individual has ended up homogenising humanity.”

Mark Power, British born 1959, The funeral of Pope John Paul II broadcast live from the Vatican, Warsaw, Poland, 2005. from the series The Sound of Two Songs, 2004–09, type C photograph 106.7 x 134.0 x 4.4 cm. Courtesy of Magnum Photos London © Mark Power / Magnum Photos

Mark Power, British born 1959, The funeral of Pope John Paul II broadcast live from the Vatican, Warsaw, Poland, 2005. from the series The Sound of Two Songs, 2004–09, type C photograph 106.7 x 134.0 x 4.4 cm. Courtesy of Magnum Photos London © Mark Power / Magnum Photos

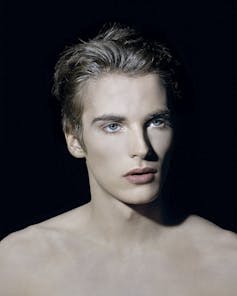

This homogenised humanity prevails in many of the photographs, whether it be in the claustrophobic clutter of the great metropolises of the “Hive” or the truly unsettling images of the “Next” section. This is a future where a perfect race appears in Valérie Belin’s models, robots replace humans in Reiner Riedler’s photographs and we leave this crowded planet in the images of Michael Najjar.

Valérie Belin, French born 1964, Untitled. from the Models II series, 2006, pigment inkjet print 130.0 x 105.0 x 4.0 cm. Courtesy Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels © Valérie Belin

Valérie Belin, French born 1964, Untitled. from the Models II series, 2006, pigment inkjet print 130.0 x 105.0 x 4.0 cm. Courtesy Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels © Valérie Belin

In navigating this extensive exhibition, you experience mixed emotions – on one hand these photographers are holding up a mirror to this concentrated global urban environment that we recognise as real and a shared experience, but on the other hand this is an exhibition of very significant art.

Many of the names of these photographers read like a roll call of some of the leading documentary and art photographers in the world.

In one of the iconic images of this exhibition, Thomas Struth’s “Pergamon Museum 1, Berlin” (2001), a huge type C photograph, our civilisation has recreated a past civilisation so that we can stand in triumph over past achievements.

The great veteran photographer, Lee Friedlander, records America through the prism of the car window, while the Canadian Edward Burtynsky presents a huge panoramic view of mass food production in his “Manufacturing #17, Deda Chicken Processing Plant, Dehui City, Jilin Province, China” (2005).

The young Russian photographer, Sergey Ponomarev, in one of the most moving photographs in the exhibition, “Migrants walk past the temple as they are escorted by Slovenian riot police to the registration camp outside Dobova, Slovenia, Thursday October 22, 2015” comments on the theme of mass migration in the era of the new world order.

Sergey Ponomarev, Migrants walk past the temple as they are escorted by Slovenian riot police to the registration camp outside Dobova, Slovenia, Thursday October, 22, 2015 2015, from Europe’s Refugee Crisis series type C photograph, 70.6 x 104.0 x 3.2 cm, Courtesy of The New York Times. © Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

Sergey Ponomarev, Migrants walk past the temple as they are escorted by Slovenian riot police to the registration camp outside Dobova, Slovenia, Thursday October, 22, 2015 2015, from Europe’s Refugee Crisis series type C photograph, 70.6 x 104.0 x 3.2 cm, Courtesy of The New York Times. © Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

There is also a powerful section on images of escape – an escape from a created reality that now imprisons us – the fake wilderness in American amusement parks recorded by the Austrian Reiner Riedler or the American Jeffrey Milstein’s “Caribbean Princess” (2014) an inkjet print from the Cruise Ships series.

Jeffrey Milstein, Caribbean Princess 2015, from the Cruise Ships series 2014, inkjet print. © Jeffrey Milstein

Jeffrey Milstein, Caribbean Princess 2015, from the Cruise Ships series 2014, inkjet print. © Jeffrey Milstein

A hallmark of a memorable exhibition is that it seduces the viewer through its sheer beauty, while at the same time making us question the reality that we inhabit.

Civilization: The way we live now is an important milestone exhibition that raises questions of the single planetary civilisation that is now evolving, where a stranger on social media may appear more real than our neighbour, and where our very future appears increasingly problematic.

Civilization: The Way We Live Now is at NGV Australia, Federation Square until 2 Feb 2020.

Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.