To understand why Australian cities are far from being meccas for walking and cycling, follow the money. Our research has collated data for all the states and territories and our three biggest cities. We found that cycling and walking receive a tiny fraction of overall transport infrastructure funding. To improve cycling and walking infrastructure in our cities, funding will have to increase significantly.

The United Nations has recommended that governments dedicate 20% of transport funding to non-motorised or active transport. To see how Australia compares against this target, we looked at budgets for three capital cities and all the states and territories. Commonwealth funding was not included because the federal government only funds active travel as part of larger infrastructure projects.

Read more: Australian cities are far from being meccas for walking and cycling

HIDDEN DATA

Compared to the widely available expenditures for roads and public transport, it’s hard to pin down spending for cycling and walking. The data are spread across a myriad of documents, and entities report them differently. For example, walking infrastructure figures might be reported separately or bundled with cycling or road projects.

Unclear reporting, in itself, indicates active travel’s low status in the transport funding hierarchy.

To gather the expenditures reported here, we had to draw on a variety of sources. Our data are not perfect or perfectly comparable across time and place, but do indicate relative spending levels.

MUNICIPAL SPENDING

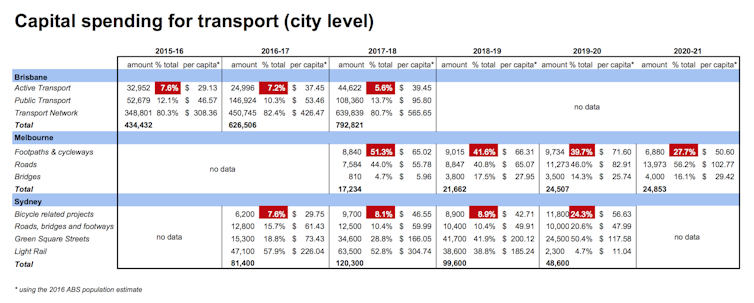

This research considers Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. For a number of years, the Bicycle Network produced the Bicycle Expenditure Index (BiXE), which examined local government spending for bicycle infrastructure. Unfortunately, 2012 was the last year that BiXE was produced. Our analysis is based on the annual budgets for the three cities instead of BiXE.

Brisbane and Sydney have been allocating a very small portion of their transport budgets (6-9%) to cycling and walking. Brisbane has the lowest active travel rates of the three cities. Despite this, its budget for walking and cycling has slightly decreased in the current cycle.

By contrast, major change is under way in Sydney. In the 2019-2020 cycle, the council has set aside nearly a quarter of its transport budget to active transport.

Funding for cycling and walking infrastructure is highlighted in red. (Click on table to enlarge.) Image: Author-provided

As for Melbourne, the city is devoting more than half of its transport budget to footpaths and cycleway projects in the current budget period. But here too the allocated budget is projected to decrease in coming years to about 28% in 2020-2021.

Most of the Melbourne City funding appears to have been dedicated to footpaths rather than cycleways. This approach will not help increase cycling rates in the inner city, which have stagnated at about 5% in recent years.

Read more: Slow cycling isn't just for fun – it's essential for many city workers

STATE AND TERRITORY SPENDING

The 2015-2016 state and territory budgets are disappointing in that they continue the trend of underfunding active transport infrastructure. The difference between active transport and road funding is staggering: most states devote less than 2% of funding to cycling.

All Australian states and territories are far below the United Nations target of 20%. The Australian Capital Territory (ACT), at 14%, is the only place that has made a real effort to meet the UN target.

Also, per capita dollar amounts devoted to active transport are low everywhere (under A$20 a year). As a benchmark, Copenhagen – regarded as the world’s best city for cycling – has spent A$30 per capita a year for the past decade.

In Australia, the ACT is an exception at A$79 per capita in 2016. In fact, the ACT has some of the highest cycling rates at metropolitan level (though this is only about 3%). Also, the Northern Territory had more than doubled its spending by 2016, rising to A$36 per capita from only A$15 in 2011.

The amounts spent “per helmet” are much larger. But, in most cases, this is only because cyclists make up a small fraction of the population.

Another way to look at road and cycling funding is “cents on the dollar” – that is, how many cents go to cycling for each dollar spent on roads. The typical amount is less than two cents – although Victoria has almost reached three cents in some years. The ACT’s spending is not shown on the graph because it is high and would distort the scale for the other states and territories.

Read more: Sidelining citizens when deciding on transport projects is asking for trouble

THE FUTURE OF CYCLING IN AUSTRALIAN CITIES

Australian cities are ideal for cycling and walking for most of the year. But cyclists and pedestrians are being short-changed while infrastructure spending continues to favour cars.

This situation reflects the blinkered vision that Australia cannot and need not be a world leader in active travel. Our cities, which have some of the widest roads in the world, are supposedly too difficult to retrofit for walking and cycling. Many older cities overseas have redesigned much narrower streets for active transport.

Low-grade shared cycling lanes in Toronto, Canada (left) and high-quality, segregated cycling paths in Bogotá, Colombia (right). Image: Dylan Passmore / Flickr, CC BY-NC

In Australia any such retrofit requires long public consultation processes. Australians must accept incremental increases in active transport funding while road funding continues to dominate transport budgets.

Not only is this vision shortsighted, it is sexist, ageist and classist. Cars cost their owners more than A$300 per week on average. This limits travel options for youth, low-income people and women. These groups are already vulnerable to transport disadvantage, and failing to fund cycling and walking projects can make their situation worse.

Mediocre active travel infrastructure is unacceptable in a wealthy OECD country. We need and can have world class active travel infrastructure. This type of investment makes economic, health and environmental sense.

Mediocre active travel infrastructure is unacceptable in a wealthy OECD country. We need and can have world class active travel infrastructure. This type of investment makes economic, health and environmental sense.

Dorina Pojani, Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning, The University of Queensland; Anthony Kimpton, Casual Lecturer in Urban Sociology and Geography, The University of Queensland; Jonathan Corcoran, Professor, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Queensland, and Neil Sipe, Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.