Quote of the week

“I have made a sculpture … you will never be finished with it – when you pass around it or see it against the sky… something new goes on all the time… together with the sun, the light and the clouds, it makes a living thing.” Jørn Utzon

A most conceptual building

The Sydney Opera House turned 50 this week. All manner of media carried copious copy with the usual suspects: Utzon’s turbulent times, cost blowouts, building difficulties, finally success. Ho hum. The building itself was barely discussed.

The architectural genius of the SOH is that it is the most conceptual building of the 20th century. Which is to say, an architecture based on beautifully interwoven design concepts. More than any other, ever.

1. Halls side by side

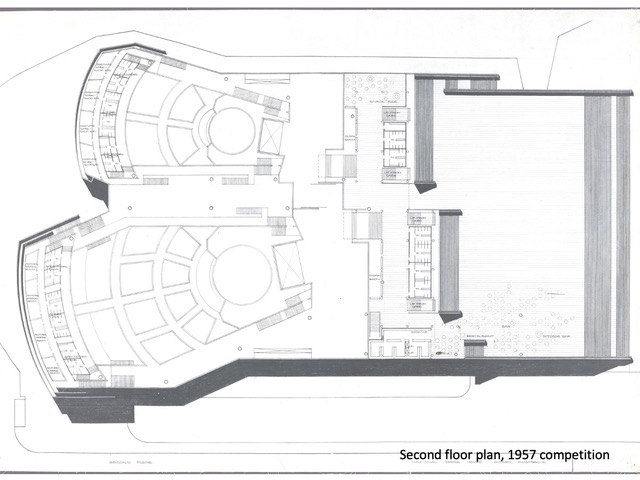

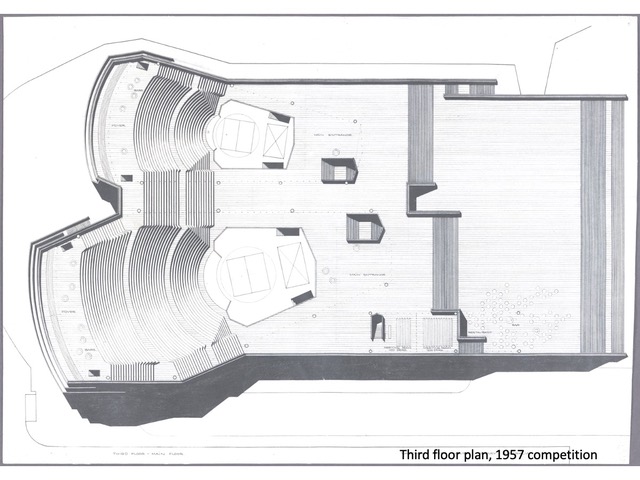

Of the 220+ entries in the 1956 competition Jørn Utzon's (number 218), was one of the very few that put the two required halls side by side. This gave equity to both halls, made the same approach to both and provided a foyer for each that faced the harbour. You’ve seen the spectacular view that results.

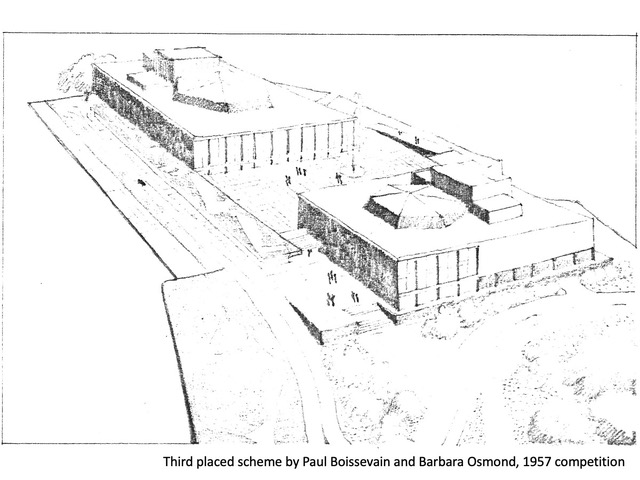

Almost all of the other entrants placed the halls front and back, one in front of the other given the narrow site, as seen the third placed scheme by Paul Boissevain and Barbara Osmond, Dutch / British, and one of the very few named women who entered.

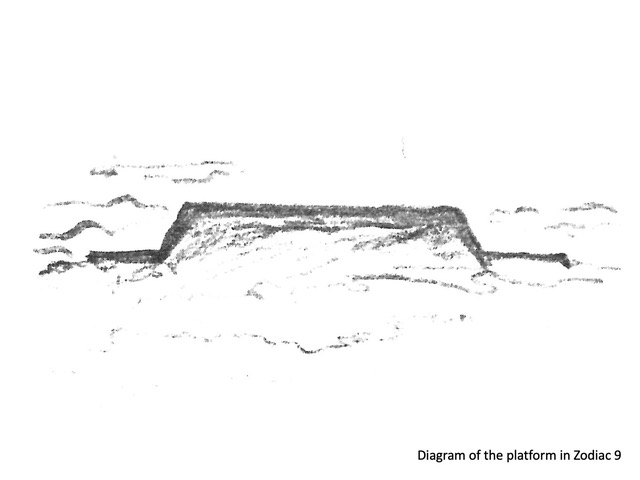

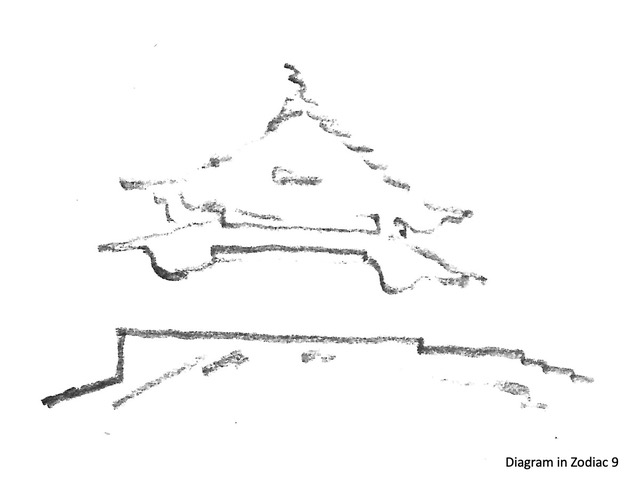

2. Mayan platforms

Utzon described how the artists would perform above the workings needed to produce the art. He envisaged a giant elevated platform, heavy and ground connected, with grand stairs similar to Mayan temples, with all the supporting activities contained within it. Above that would a completely different lightweight structure covering the halls. Those grand stairs are now Sydney’s Piazza, obligatory photography for all visiting groups.

3. Greek amphitheatres.

The solid ‘stone’ platform (eventually dressed in washed aggregate concrete) would then be ‘hollowed out’ to create two amphitheatres, similar to those carved into a hillside at Delphi that Utzon had seen in Greece. His vision had you enter from above the auditorium, feeling the security of enclosure, and descend to your seats.

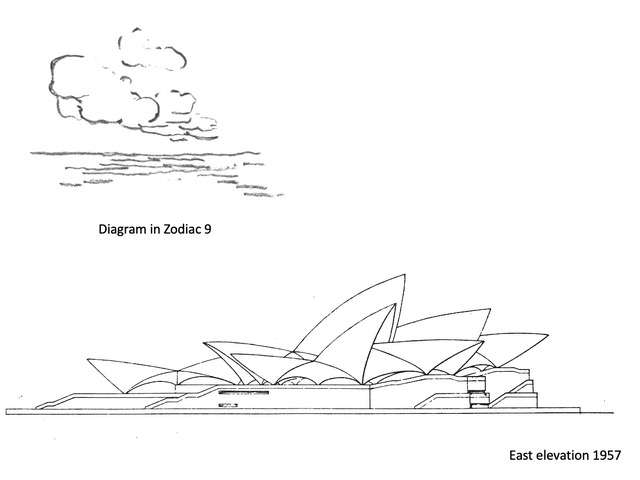

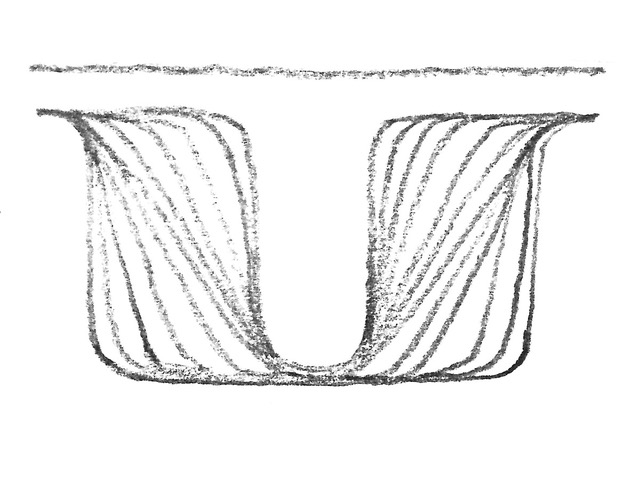

4. The floating ‘fifth façade’

Utzon's original idea was a flowing roof form, floating over the heavy base. He called the roof on the highly visible and exposed site, the ‘fifth façade’. The ideagram is clouds floating over the base. He drew it as thin shells, an emerging technology but not constructed at that scale. Those shells transmogrified more vertical shells, subject to further design concepts.

5. The walnut analogy

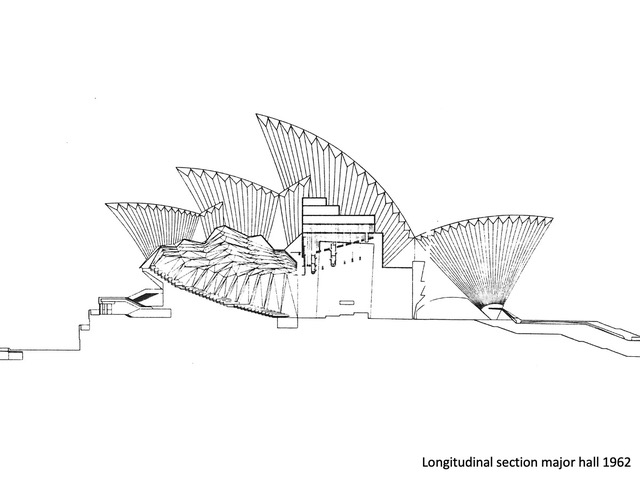

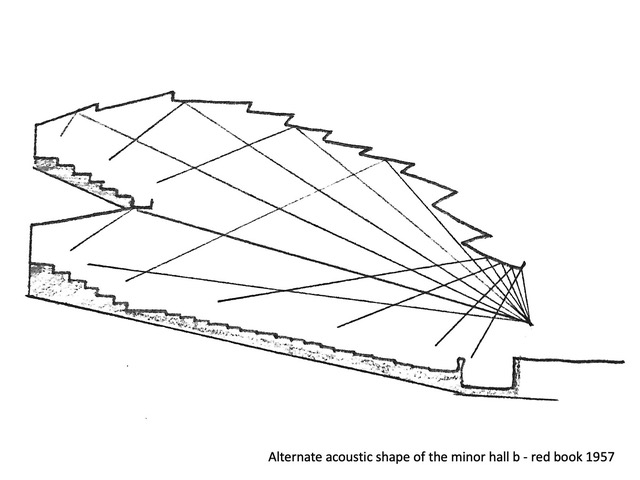

In the SOH, and the later Bagsvaerd Church (pronounced Bows-vair), Utzon was developing an idea pioneered by Alvar Aalto, of the interior and exterior of a building being separate entities. Unlike classical architecture, with interiors fitted to ordained proportions, or 20th century modernism that had ‘form follows (internal) function’, Utzon completely divorced the inside and out.

His analogy was the ‘walnut’, a ‘hard’ exterior to defend against climate and weathering, protects a ‘soft’ acoustic-based interior. An acoustic form is not a structural form, so the interior shape would be supported, indeed suspended, by the external envelope that would span and ‘float’ over.

6. The space between

Utzon proposed that the walnut’s interstitial space, between hard external shell and the soft interior, be circulation for patrons as they ascended to the harbour foyer and the auditoriums’ entrances. Envisaged as organic, between arches holding the roof and the acoustic hall that you were about to enter. The idea still holds, even though the interior ballooned out, and the arches fattened inwards.

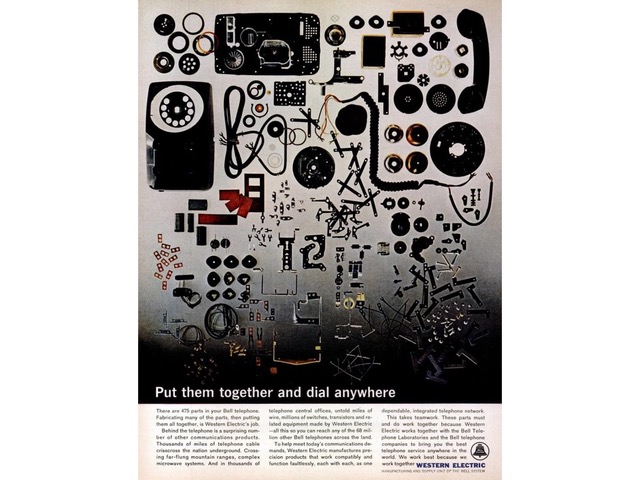

6. Prefabrication

In his architectural studio at the site, Utzon had an image of a telephone stripped down to a hundred parts, with the motto: “Put them together and dial anywhere”. He saw this as analogous to buildings being assembled from factory-made parts rather than constructed on site. Presaging the movement to prefabrication so central to advanced contracting today.

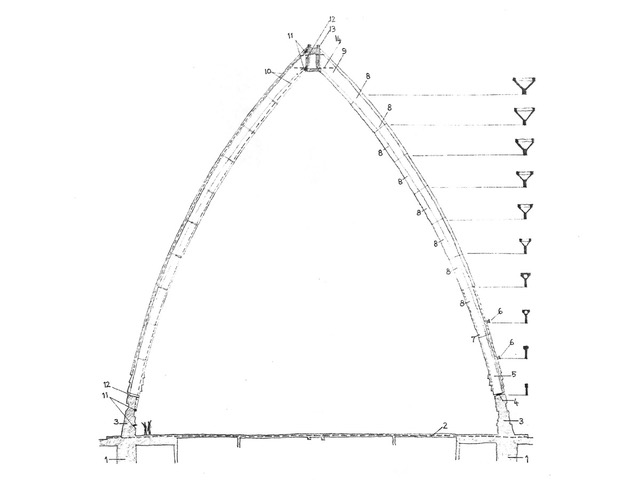

7. The concrete shells

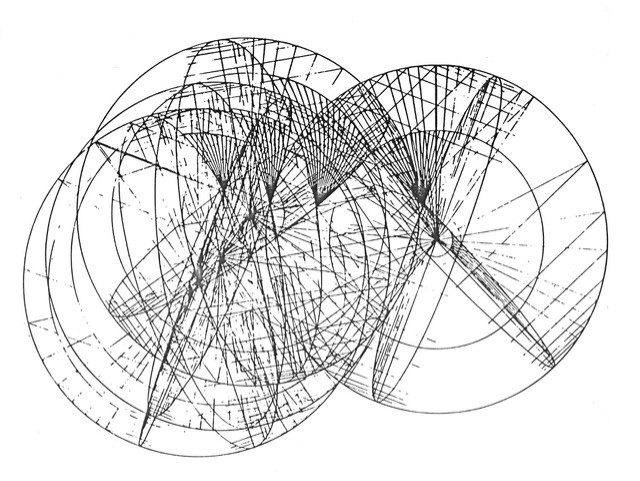

Once it was established that the original lightweight hyperbolic or paraboloid shells could not be built, a new solution was developed by Utzon, in conjunction with Peter Rice from ARUPS, premier engineer of the age who also designed the Pompidou with Piano and Rogers and Lloyds Bank. Instead of an undulating form, a stricture structure was required, to be based on a ‘great circle’, famously developed by Utzon when cutting up oranges for breakfast.

Pointed Gothic arches, every curve made from the same sized circle, gave the form, tapered and hollowed out like the bones of a bird's wing. They were not identical, but readily determined into integrated modular sizes, the structure was made repetitive in a premanufactured process.

Cranes hoisting those panels, made in a concrete yard on site, and placing them on a temporary steel substructure is one of the key images of the project’s construction.

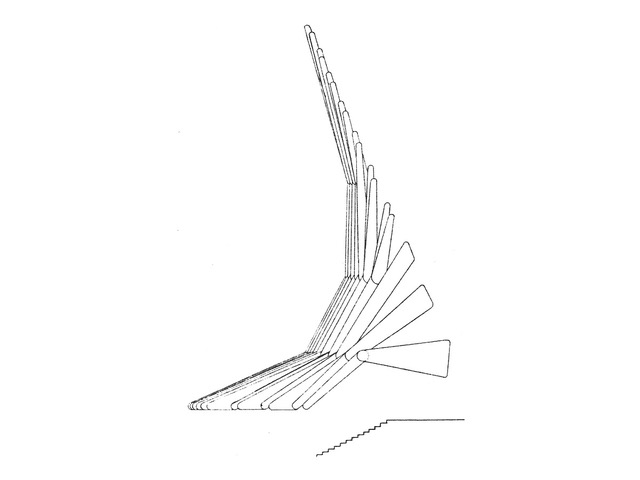

8. The timber interior

Utzon envisaged the soft acoustic interior made from giant prefabricated box sections of plywood, 60 to 70 feet long (before Metrication). Designed as hanging acoustic shapes, suspended in one piece from the concrete ribs. Public Works, increasingly antagonistic, openly criticised Utzon as being unrealistic, inept even, as they would be too long to be maneuvered through Sydney’s narrow streets.

Why streets?, he replied. Ralph Symonds plywood factory was on the Parramatta River (next to the eventual Olympic site). The plywood boxes, made there, would be floated down the river, to the harbour, to arrive at the Opera House. An aquatic drama orchestrated by a notable sailor, later played out incidentally with Aldo Rossi’s ‘Theatre of the world’, floating down the Venice Grand Canal.

9. Tiled panels

Having established that a smooth concrete finish was not possible, rather prefabricated concrete arches, Utzon continued the prefabrication idea with standardised and regularly spaced panels as the roof. Covered in protective tiles (made in his native Denmark), the body was gloss, reading as a single continuous surface, and matte at the edge articulating the prefabrication of placed panels.

10. The glazing mullions

The ends of the arches are glazed with views north and south. Huge areas, Utzon saw them as dynamic folded surfaces, with articulated mullions, expressing both the drapery drop, and the bowed face. Envisaged in boxed plywood (again) it was one of the most contentious issues at the time his departure. The changed steel replacements by Peter Hall are controversial – but for me they retain the essence of Utzon’s ideas.

11.The arrival

As well as the stairs to the platform, Utzon rethinks the ‘porte cohere’, literally the covered arrival. Again Utzon challenges: one giant opening for cars and pedestrians to enter, spanned with cranked precast beams, made on site. Its structural shape gives undulating curves below to support the perfectly flat platform over.

12. The terrace

Ascending the front stairs, you reach an interim terrace, and then the huge ‘Mayan platform’, from which you look back at the city and over the harbour. It was vital for Utzon that it appeared perfectly flat, without the troughs of tiling. He designed large precast panels in washed aggregate concrete fitted on (what we now call) pedestals, all flat but allowing drainage between the panels. Now common, in the early sixties it was a radical idea, particularly in such large panels.

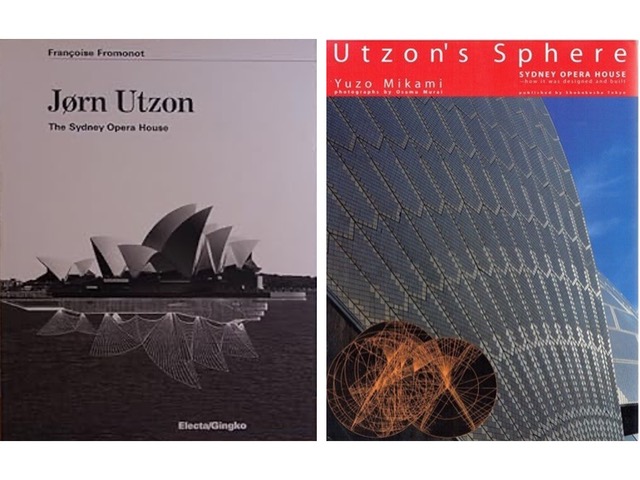

Bookends

There are dozens of books on the opera house. Most of them deal with the narrative. Here’s two that address the architectural design of the building. French critic Francoise Fromonot’s book is an outsider’s perceptive and penetrating view. Yuzo Mikami, a Japanese architect, was the first employee in Utzon's Sydney office and remained for the entire project. Utzon's Sphere is uniquely insightful view from the inside. Sadly the best book on the SOH is now unavailable.

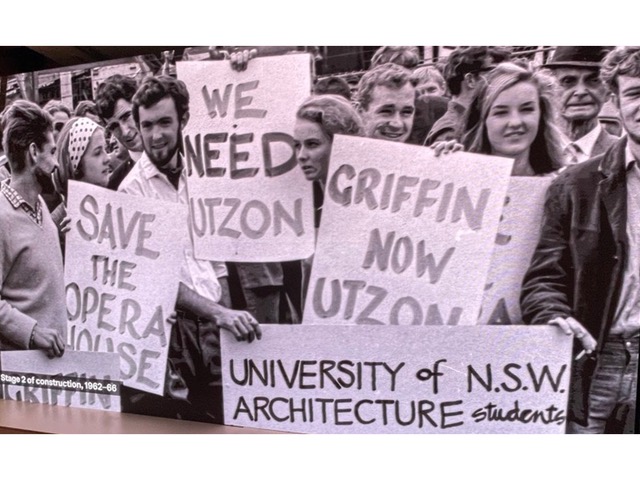

Signs off

In 1966, as Utzon was pushed out, architecture students protested, with correctly lettered signs (they were taught and inspired by George Molnar). This image is from a digital presentation at the current exhibition at the Museum of Sydney.

Next week

What to do with building bad?

Tone Wheeler is an architect /adjunct prof UNSW / president AAA

The views expressed are his.

These Design Notes are Tone on Tuesday #185.

Past Tone on Tuesday columns can be found here

Past A&D Another Thing columns can be found here

You can contact TW at [email protected]