More than two years on from the sudden closure of Victoria’s Hazelwood coal power station, quite a mess remains. It is clear the federal government’s market interventions have not worked. Electricity prices are higher and supply is tight. Consumers are not happy.

In the face of this, federal and state governments have felt pressured to act – especially after several severe blackouts attracted fever-pitch media coverage and prompted a national debate about electricity reliability. But their approach has been ad hoc and has made things worse in the long run.

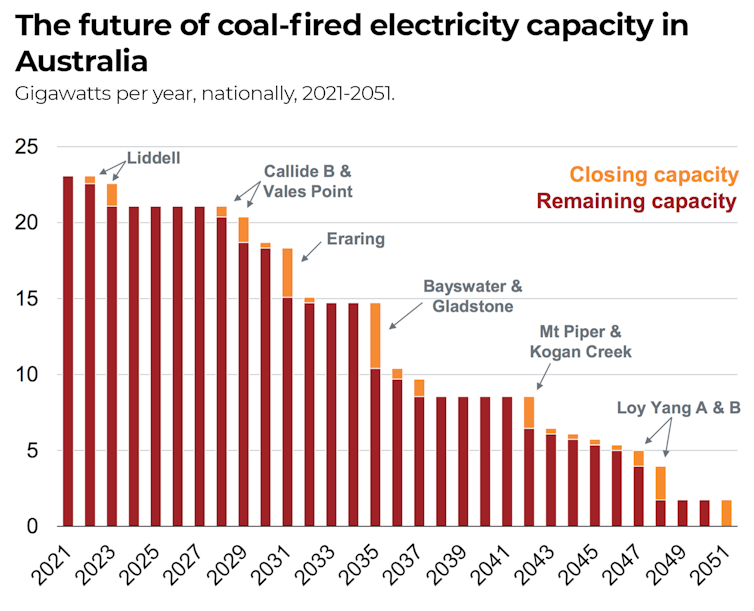

Australia is in the midst of a great energy transition. The nation’s entire coal fleet will close over the next few decades, and the government must urgently improve its policy response or electricity consumers will continue to suffer. We propose a solution that ensures coal plants close in an orderly way.

A high-voltage electricity transmission tower in Brisbane. A new report says governments are hindering the clean energy transition. AAP/Darren England

A high-voltage electricity transmission tower in Brisbane. A new report says governments are hindering the clean energy transition. AAP/Darren England

We can’t afford a repeat of the Hazelwood mess

The aftermath of the sudden Hazelwood closure is a good case study in failed government intervention.

Hazelwood closed in March 2017 after supplying Victoria with cheap brown coal-fired electricity for more than half a century. The plant’s owner, French energy company Engie, gave only five months’ notice of the shutdown. This left no time to build replacement electricity generation, so prices rose and supplies became less reliable.

In the years since Hazelwood’s closure, the federal government failed to clear up more than a decade of uncertainty around national climate and energy policy – including last year when it dumped the National Energy Guarantee. This has left investors wondering when a framework to cut emissions in the electricity sector will be imposed.

Instead of creating investor certainty, the federal government has adopted a “picking winners” approach. It plans to build new generation assets such as the Snowy 2.0 pumped hydro project, and subsidise others through a program of underwriting investments. Alongside this, the government’s proposed “big stick” laws would give it vast powers including those to break up big energy companies. Our research has confirmed this has a chilling effect on investment.

The sudden closure of large coal power stations is challenging enough without being made worse by ill-conceived policy responses. Hazelwood will be the first of many closures. Australia’s entire coal fleet is expected to retire over coming decades as it ages and gets displaced by low-cost solar and wind energy.

The Grattan Institute, CC BY-ND

The Grattan Institute, CC BY-ND

Flogging the life out of coal plants is not the answer

The crucial lesson from Hazelwood is that Australia needs adequate notice of impending coal plant closures. This allows timely replacement investment to occur, minimising the price and reliability impacts on consumers.

New South Wales’ Liddell power station is due to close next and its owner AGL has given plenty of notice. In 2015 it announced a 2022 closure, and this year firmed up its plans for full closure by 2023. One unit of four will close in 2022.

Read more: When it comes to climate change, Australia's mining giants are an accessory to the crime

Federal Energy Minister Angus Taylor is so concerned at Liddell’s closure he set up a taskforce to examine how to manage it, including extending its life or replacing the lost generation like-for-like.

But his concerns are misplaced. The Australian Energy Market Operator’s 2019 reliability projection for New South Wales is that the outlook is improving more rapidly than it was in 2018. About 2.3 gigawatts of solar and wind energy has been committed in NSW since the start of 2017 – and more is planned.

The best way to maintain reliability is through investment – not by trying to keep an ageing power station running on hot summer days.

The now-closed Hazelwood coal-fired power station in the Latrobe Valley, Victoria. Global Warming Images/Cover Images

The now-closed Hazelwood coal-fired power station in the Latrobe Valley, Victoria. Global Warming Images/Cover Images

Laws on coal plant closures must grow teeth

Liddell’s closure is very likely to prove manageable. But this cannot be taken for granted in all future cases.

A new rule introduced late last year requires generators to give at least three years’ notice of closure. It’s a step in the right direction, but the rule lacks teeth. The penalties for non-compliance are small, and the mechanism could be gamed by generators nominating a closure date and then continuously delaying closure. We need better insurance to avoid future disruptive closures.

Past Australian experience gives some lessons on what not to do. In 2011 the Gillard Labor government proposed paying coal generators to close, on the grounds that otherwise they might continue operating indefinitely. Four of the five short-listed generators have since closed – without being paid a cent of government money. We are now dealing with the opposite problem, but the lesson holds – taxpayers will be taken for a ride if government money is used to delay or otherwise “manage” coal closures.

International experience is not likely to translate well to Australia. Germany’s coal closure commission built on deep cooperation between business, unions and governments that is not present here. The UK and Canada legislated coal phase-outs, but they did so at a time when coal provided only 10 percent of their power, compared to more than 60 percent in Australia today.

Prime Minister Julia Gillard during a visit to the Acciona windfarm near Gunning, NSW, in 2011. Labor’s incentives for coal stations to close were also misguided. AAP/Alan Porritt

Prime Minister Julia Gillard during a visit to the Acciona windfarm near Gunning, NSW, in 2011. Labor’s incentives for coal stations to close were also misguided. AAP/Alan Porritt

Make coal plants guarantee orderly closure

The Grattan Institute’s latest report, Power play: how governments can better direct Australia’s electricity market, proposes a new approach. Coal generators should be required to put money – indicatively several hundreds of millions of dollars each – into a fund, managed by an independent third party, to be held as security. Generators would be allowed to nominate their own closure window, but would get these funds back only if they closed within this window – providing a strong financial incentive for predictable and orderly closure.

Circumstances change and generators cannot reasonably fix closure decades in advance. To balance flexibility and certainty, younger generators would be allowed to nominate relatively long windows, but they would need to tighten these windows as they age.

Read more: How to transition from coal: 4 lessons for Australia from around the world

Limited exemptions would be available if early closure did not harm the reliability of the market, or conversely if continued operation of the coal plant in question was absolutely necessary to maintain reliability.

This policy would come with costs. Collectively generators would need to place several billions of dollars into the fund. As generators have a higher cost of capital than would be earned on the held funds, this would cost them, collectively, several hundreds of millions of dollars a year. But the measure would provide low-cost insurance against the destabilising effect of poorly managed coal closures on the A$18 billion National Electricity Market.

The policy would give a clear signal for investment in new, clean power supply before – not after – coal closures, and better manage Australia’s energy transition.

Guy Dundas, Energy Fellow, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.