House prices may have finally peaked, at least in Melbourne and Sydney. But a slight cooling in some overheated cities makes little difference to overall housing affordability in Australia, which has declined significantly over the past two decades.

The politics around housing tax reform remains as difficult as ever. But reform to capital gains and negative gearing, alongside a shift to property taxes instead of stamp duty, would improve affordability while increasing government revenue.

Our modelling shows the key is incremental change. Gradual reform over a decade or more minimises the impact on government budgets, households and housing markets.

Read more: Three charts on: poorer Australians bearing the brunt of rising housing costs

It’s important to adopt a holistic approach to housing tax reform that considers the combined impact of the tax treatment of income from housing investment, state and local government property taxes and the interaction between housing and retirement savings.

This will take political leadership and cooperation between governments at federal, state and local levels.

Although such coordination is a challenge, there are successful precedents, such as the introduction of the National Competition Policy in the 1990s.

Capital gains and negative gearing

Gradually – over the space of a decade – reducing the generosity of capital gains tax discounts from 50 percent to 30 percent would have little impact on average “mum and dad” investors.

The exact impact depends on incomes, interest rates and capital growth.

The same applies to negative gearing where a cap on housing-related tax deductions could be phased in over a 10-year period, with an initial A$20,000 cap to be reduced by approximately A$1,500 per year (the precise amount would depend on market conditions) until it reached A$5,000.

The modelling suggests that in the first year, with a A$20,000 negative gearing cap, only 6.3 percent of all property investors (1.1 percent of all taxpayers) would be affected.

Even after a decade, only 28.5 percent of high income property investors would pay more tax, with the majority of “mum and dad” investors paying no more tax.

Read more: Three charts on: the great Australian wealth gap

This reform would save the federal government more than A$1.7 billion from the annual A$3.04 billion cost of negative gearing deductions.

This revenue could be reinvested in social and community housing. Over the long term, establishing a broad-based property tax is more efficient and fairer than state governments continuing to rely on stamp duty.

Complementing the changes to stamp duty and negative gearing should be a short-term simplification of stamp duty, with this gradually (over 5–20 years) evolving into a broad-based property tax.

Phasing out stamp duties

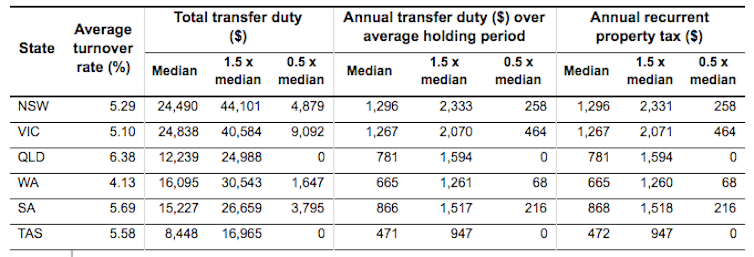

We modelled the property tax rates and thresholds each state would have to charge if they phase out stamp duties on residential properties over a decade.

Annual tax rates in the first year of the transition vary from A$47 in Tasmania to A$129 in NSW which would fund a 10 percent cut in stamp duties. In order to fully fund the abolition of stamp duties, annual property taxes would have to increase to A$472 in Tasmania and A$1,293 in NSW over a decade.

For the government this would be revenue neutral, but the overall tax burden would shift from prospective home buyers to those who already own residential property. This would not only improve intergenerational equity, but be more efficient and provide more stable revenue for state governments.

Image: Author provided

Image: Author provided

It’s also fairer if the pension asset test reflects the value of the family home, although any changes to stamp duties or retirement savings policy should be complemented by a comprehensive deferral scheme to allow “asset rich, income poor” pensioners to be able to access the age pension and to age at home.

Read more: Negative gearing reforms could save A$1.7 billion without hurting poorer investors

A staged and gradual change would have little impact on average Australians, but would improve access to affordable, secure and suitable housing. This would benefit not only Australia’s community well-being, but also the economy.

However, the prospects of reform will depend on how the changes are communicated and perceived.

Widespread support is more likely if state and national leaders move beyond the current narrowly focused debate over taxation and promote the wider community benefits of a fairer property tax system. Now more than ever we need a holistic, long-term plan to address the legacies of the property boom and to deliver better housing outcomes for all Australians.

Widespread support is more likely if state and national leaders move beyond the current narrowly focused debate over taxation and promote the wider community benefits of a fairer property tax system. Now more than ever we need a holistic, long-term plan to address the legacies of the property boom and to deliver better housing outcomes for all Australians.

Richard Eccleston, Professor of Political Science; Director, Institute for the Study of Social Change, University of Tasmania; Julia Verdouw, Research fellow, Housing and Community Research Unit (HACRU), University of Tasmania, and Kathleen Flanagan, Research Fellow & Deputy Director, HACRU, University of Tasmania

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.