Green cement a step closer to being a game-changer for construction emissions

We have developed a water-resistant MOC, a “green” cement that could go a long way to cutting the construction industry’s emissions and making it more sustainable.Concrete is the most widely used man-made material, commonly used in buildings, roads, bridges and industrial plants. But producing the Portland cement needed to make concrete accounts for 5-8 percent of all global greenhouse emissions. There is a more environmentally friendly cement known as MOC (magnesium oxychloride cement), but its poor water resistance has limited its use – until now. We have developed a water-resistant MOC, a “green” cement that could go a long way to cutting the construction industry’s emissions and making it more sustainable.

Producing a tonne of conventional cement in Australia emits about 0.82 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO₂). Because most of the CO₂ is released as a result of the chemical reaction that produces cement, emissions aren’t easily reduced. In contrast, MOC is a different form of cement that is carbon-neutral.

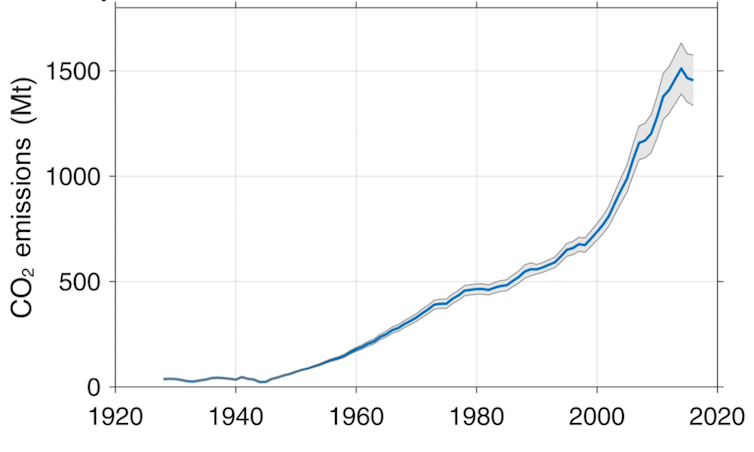

Global CO₂ emissions from rising cement production over the past century (with 95 percent confidence interval). Source: Global CO2 emissions from cement production, Andrew R. (2018), CC BY

What exactly is MOC?

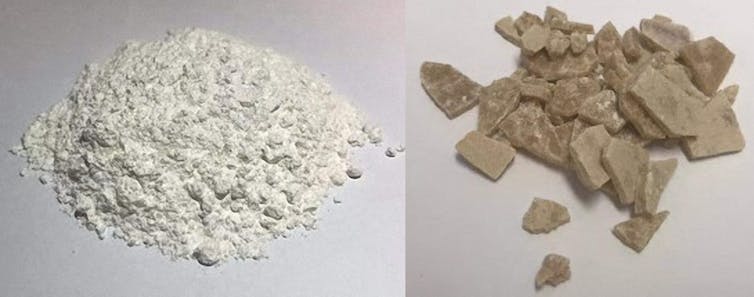

MOC is produced by mixing two main ingredients, magnesium oxide (MgO) powder and a concentrated solution of magnesium chloride (MgCl₂). These are byproducts from magnesium mining.

Magnesium oxide (MgO) powder (left) and a solution of magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) are mixed to produce magnesium oxychloride cement (MOC). Author provided

Many countries, including China and Australia, have plenty of magnesite resources, as well as seawater, from which both MgO and MgCl₂ could be obtained.

Furthermore, MgO can absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere. This makes MOC a truly green, carbon-neutral cement.

Read more: Greening the concrete jungle: how to make environmentally friendly cement

MOC also has many superior material properties compared to conventional cement.

Compressive strength (capacity to resist compression) is the most important material property for cementitious construction materials such as cement. MOC has a much higher compressive strength than conventional cement and this impressive strength can be achieved very fast. The fast setting of MOC and early strength gain are very advantageous for construction.

Although MOC has plenty of merits, it has until now had poor water resistance. Prolonged contact with water or moisture severely degrades its strength. This critical weakness has restricted its use to indoor applications such as floor tiles, decoration panels, sound and thermal insulation boards.

How was water-resistance developed?

A team of researchers, led by Yixia (Sarah) Zhang, has been working to develop a water-resistant MOC since 2017 (when she was at UNSW Canberra).

Adding industrial byproducts fly ash (above) and silica fume (below) improves the water resistance of MOC. Author provided

To improve water resistance, the team added industrial byproducts such as fly ash and silica fume to the MOC, as well as chemical additives.

Fly ash is a byproduct from the coal industry – there’s plenty of it in Australia. Adding fly ash significantly improved the water resistance of MOC. Flexural strength (capacity to resist bending) was fully retained after soaking in water for 28 days.

To further retain the compressive strength under water attack, the team added silica fume. Silica fume is a byproduct from producing silicon metal or ferrosilicon alloys. When fly ash and silica fume were combined with MOC paste (15 percent of each additive), full compressive strength was retained in water for 28 days.

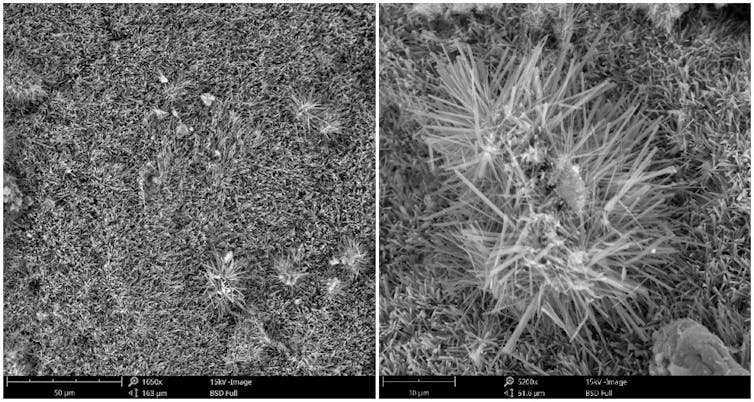

Both the fly ash and silica fume have a similar effect of filling the pore structure in MOC, making the cement denser. The reactions with the MOC matrix form a gel-like phase, which contributes to water repellence. The extremely fine particles, large surface area and high reactive silica (SiO₂) content of silica fume make it an effective binding substance known as a pozzolan. This helps give the concrete high strength and durability.

Scanning electron microscope images of MOC showing the needle-like phases of the binding mechanism. Author provided

Read more: We have the blueprint for liveable, low-carbon cities. We just need to use it

Although the MOC developed so far had excellent resistance to water at room temperature, it weakened fast when soaked in warm water. The team worked to overcome this by using inorganic and organic chemical additives. Adding phosphoric acid and soluble phosphates greatly improved warm water resistance.

Examples of building products made using MOC. Author provided

Over three years, the team has made a breakthrough in developing MOC as a green cement. The strength of concrete is rated using megapascals (MPa). The MOC achieved a compressive strength of 110 MPa and flexural strength of 17 MPa. These values are a few times greater than those of conventional cement.

The MOC can fully retain these strengths after being soaked in water for 28 days at room temperatures. Even in hot water (60˚C), the MOC can retain up to 90 percent of its compressive and flexural strength after 28 days. The values remain as high as 100 MPa and 15 MPa respectively – still much greater than for conventional cement.

Will MOC replace conventional cement?

So could MOC replace conventional cement some day? It seems very promising. More research is needed to demonstrate the practicability of uses of this green and high-performance cement in, for example, concrete.

When concrete is the main structural component, steel reinforcement has to be used. Corrosion of steel in MOC is a critical issue and a big hurdle to jump. The research team has already started to work on this issue.

If this problem can be solved, MOC can be a game-changer for the construction industry.

Read more: The problem with reinforced concrete ![]()

Yixia (Sarah) Zhang, Associate Professor of Engineering, Western Sydney University; Khin Soe, Research Associate, School of Computing, Engineering and Mathematics, Western Sydney University, and Yingying Guo, PhD Candidate, School of Engineering and Information Technology, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles