Melbourne is growing faster than most cities of similar size in developed countries. Population growth averaged more than 2.5 percent a year between 2011 and 2018.

Other international cities that are also known for their livability typically recorded slower population growth than Melbourne. For example, over the decade to 2016, Vienna grew about half as fast as Melbourne and Greater Vancouver about one-third slower. Vienna and Vancouver are also smaller cities than Melbourne.

Melbourne is also fast becoming an economically and socially polarised city. Cheaper housing may attract people to outer suburban living, but it comes at a price.

Read more: Our big cities are engines of inequality, so how do we fix that?

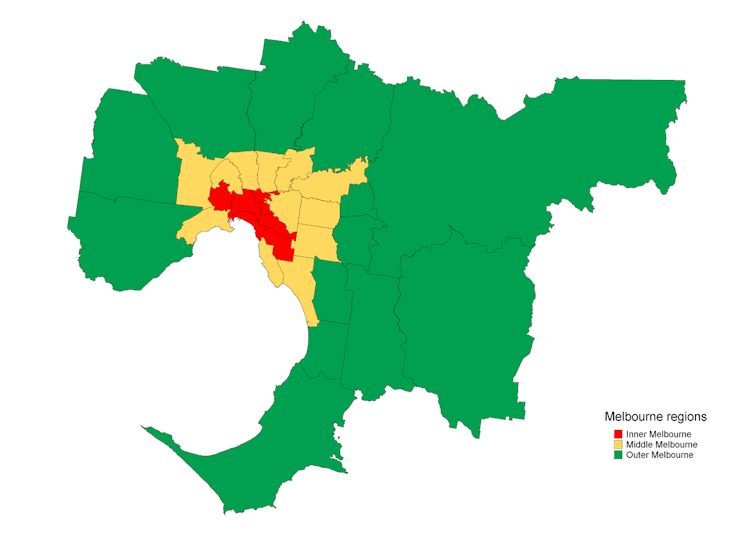

If Melbourne is divided into inner, middle and outer urban areas, each containing about one-third of the city’s jobs, the greatest share of the city’s population (46.6 percent) lives in the outer local government areas (LGAs). This share is increasing as population grows rapidly, accounting for 57.5 percent of the growth between 2011 and 2016.

Inner, middle and outer Melbourne, each area holding approximately one-third of jobs in Melbourne. Author provided

Inner, middle and outer Melbourne, each area holding approximately one-third of jobs in Melbourne. Author provided

At the same time, these outer LGAs have the fewest jobs per 1,000 residents. Many workers have to make long commuting trips, with associated congestion impacts.

What are the consequences of this pattern of growth?

Our newly published research examines the capacity of Melbourne residents to capture income, as well as the findings on some important social outcomes.

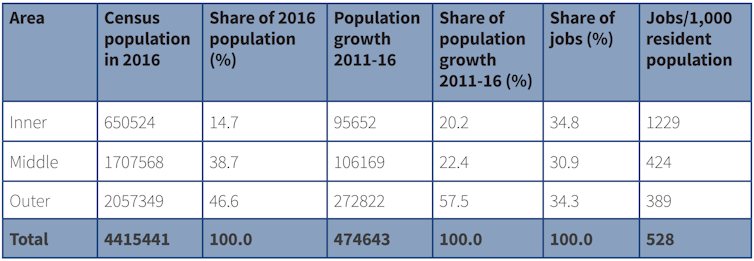

Population growth and jobs in Melbourne

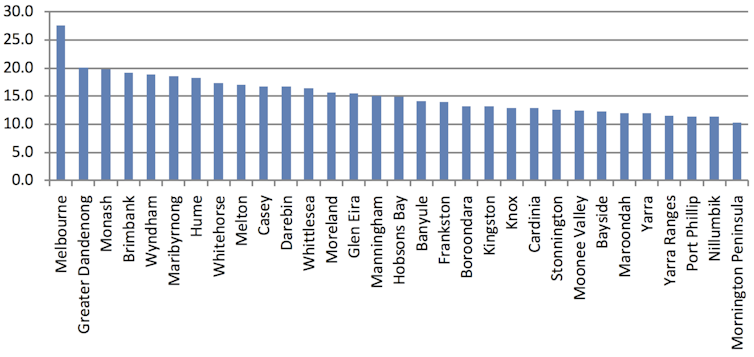

From Australian Bureau of Statistics (n.d.), Quickstats, Author provided

From Australian Bureau of Statistics (n.d.), Quickstats, Author provided

Over the 1992-2017 period, relative to Victorians as a whole, residents in each of the six fastest-growing outer Melbourne LGAs (Cardinia, Casey, Hume, Melton, Whittlesea and Wyndham) went backwards in terms of their share of income from economic activity.

The findings at LGA level show a number of quite strong spatial associations. Differences in travel time or distance to central Melbourne have particularly clear impacts. As travel times from an LGA to central Melbourne increase, we see declines in:

- population and job densities

- median house prices

- capital stock per person

- the proportion of higher educated people

- the proportion of jobs that are high-tech

- LGA productivity

- trust in others

- the proportion of people living near public transport, with public transport use to get to work also declining.

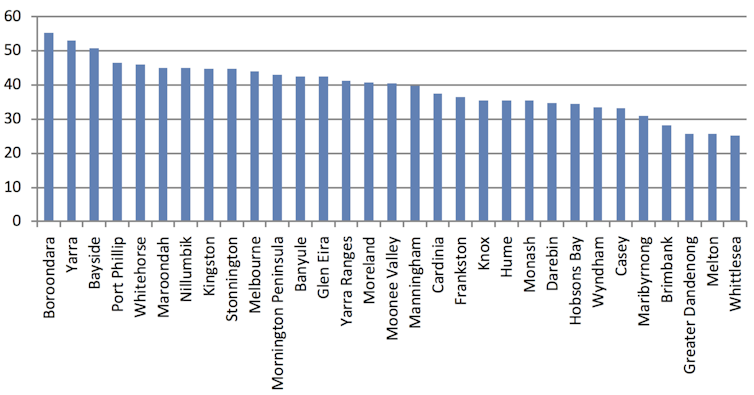

Proportion of LGA residents who think most people in general can be trusted

health.vic, Author provided

health.vic, Author provided

We see increases in:

- open space per resident

- car use to get to work

- the proportion of commutes longer than two hours

- reports of heart disease and obesity.

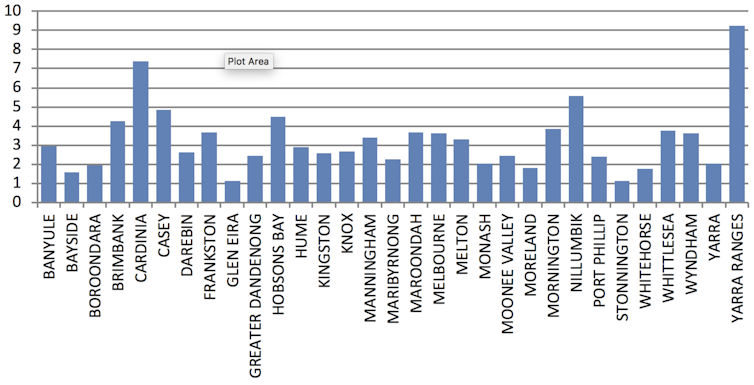

Hectares of public open space per 1,000 residents

Victorian Planning Authority data, Author provided

Victorian Planning Authority data, Author provided

These correlations suggest cheaper housing and better access to open space, which may attract people to outer suburban living, come at a price. These costs are commonly associated with the lower population and job densities at greater distances from central Melbourne.

The fastest-growing outer suburbs tend to show lower levels of some of the drivers or social conditions needed to achieve social inclusion, well-being and health. For example, additional challenges can be seen in higher levels of child development vulnerability, which tend to lead to early school leaving and youth unemployment. This can reduce the ability of individuals to be productive, while at the same time increasing societal expenses in areas such as welfare payments, health costs, law enforcement and remediation costs of family violence and substance abuse.

Youth (age 15-19) unemployment rates by LGA

health.vic, Author provided

health.vic, Author provided

Increasing inequality, social, congestion and productivity costs are linked with infrastructure spending that has been too low to meet the needs of the rapidly growing population. The research suggests a backlog of around A$125 billion to enable the six fastest-growing outer LGAs to achieve growth in gross regional product per resident of working-age population in line with the state average. Additional spending will be needed to cater for subsequent population growth and to tackle problems beyond the six outer growth LGAs, such as traffic congestion and crowded public transport.

Read more: Some suburbs are being short-changed on services and liveability – which ones and what's the solution?

What can be done about this?

Steps can be taken to reduce the growing scale of future infrastructure spending. These include a more determined focus on delivering the intent of Plan Melbourne 2017-50 that Melbourne becomes a more compact city. This would mean a much higher share of population growth is located in inner and middle suburbs with good public transport access, particularly to the CBD and to the inner and middle urban National Employment and Innovation Clusters identified in the plan.

Outer urban densities also need to increase. There must be a greater focus on delivering a city of 20-minute neighbourhoods. This calls for higher levels of local services, including bus and active transport opportunities (cycling and walking), provided in a more timely manner. A focus on big infrastructure projects can crowd out attention on such locally important priorities.

Read more: A 20-minute city sounds good, but becoming one is a huge challenge

Regional Victoria can play a bigger role in catering for population growth. However, to do so sustainably it needs to substantially increase its non-farm productivity. This was about one-fifth higher than in Melbourne 20 years ago but is now about one-fifth lower, as Melbourne’s knowledge economy has boomed.

The research does not take account of many other impacts of high population growth. Among these are the loss of ecosystem services, the loss of food-growing land through urban sprawl, increasing freshwater scarcity, and the transport sector’s greenhouse gas emissions. These issues all have impacts on productivity, health and well-being.

John Stanley, Adjunct Professor, Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, University of Sydney Business School, University of Sydney; Janet Stanley, Principal Research Fellow – Urban Social Resilience, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, University of Melbourne, and Peter Brain, Executive Director, National Institute of Economic and Industry Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.