Higher density and diversity: apartments are Australia at its most multicultural

Increasing numbers of city dwellers live in apartments. This is particularly the case for migrants. And that makes apartment buildings important hubs of multiculturalism in our cities.

Increasing numbers of city dwellers live in apartments. This is particularly the case for migrants. And that makes apartment buildings important hubs of multiculturalism in our cities.

However, our recent research shows that researchers and policymakers have largely overlooked the implications of this combination of increasing cultural diversity and increasing housing density.

We live in an environment of increasing cultural diversity. But we also see increasing racism in Australian society, as well as a rise in racialised tension about Chinese property buyers.

Read more: Contested spaces: living next door to Alice (and Anh and Abdullah)

These developments suggest we need to pay more attention to how to make apartment buildings work for residents from many different cultural backgrounds.

This is essential to support social cohesion, or the positive social relationships that bond members of society. When social cohesion is weakened, we see a lack of trust and reductions in people’s sense of belonging and their willingness to participate and help others. This, in turn, can damage people’s health and well-being, as well as fuelling broader political instability.

Increasing density

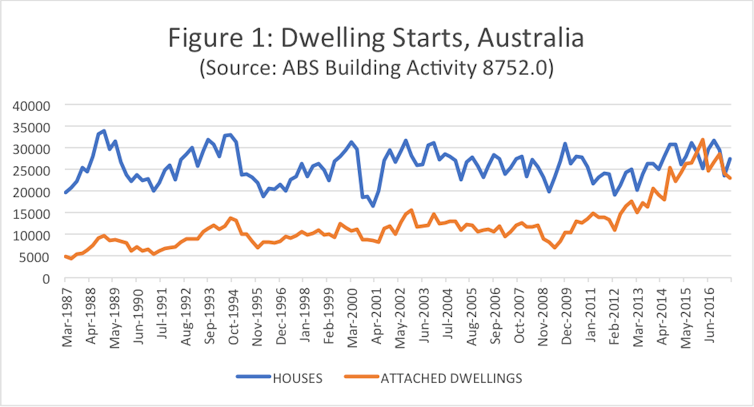

In 2015, we passed an important, but largely unrecognised, milestone in Australia. It was the first year in the country’s history that dwelling starts for attached properties overtook those for detached houses.

This should perhaps come as no surprise. State governments have for many years been pushing for more apartments to be built.

Australia is not alone in this regard. Countries around the world have been promoting “compact city” policies that focus on building up rather than building out.

Around Australia, almost one in ten people now live in apartments. However, the proportions are much higher in our major cities.

Read more: Becoming more urban: attitudes to medium-density living are changing in Sydney and Melbourne

Across the Greater Sydney metropolitan area, for example, 30 percent of residents live in apartments. In some inner-city suburbs, apartments are home to the vast majority of residents, including in Pyrmont, Zetland and Ultimo (see Table 1 below). Beachside locations such as Surfers Paradise, Queensland, and Glenelg, South Australia, also have high proportions of apartment residents.

Increasing diversity

Apartment residents are very diverse culturally. Across Australia, more than half of apartment residents – 56 percent, compared to 33 percent of all Australian residents – are migrants. Of these, the biggest group (26 percent of apartment residents) are migrants born in Asia.

Nationwide, only 7 percent of Australian-born people live in apartments. For those born in northeast Asia (including China), the figure is 31 percent. And for those born in southern and central Asia (including India), it’s 26 percent.

Looking again at Greater Sydney, housing density and cultural diversity are clearly correlated. The Sydney suburbs where more than 90 percent of residents live in apartments also have high concentrations of overseas-born migrants.

Challenges of apartment living

While apartment living is unfamiliar to many Australian-born residents, Australian apartment lifestyles and norms can be even further from what migrants are used to. Our research, based on interviews with Sydney-based strata managers, shows that social and cultural differences can contribute to tensions within apartment buildings. These might be about shoes left in common areas, or washing hung on balconies, or “offensive” cooking smells wafting beyond kitchen walls.

Tensions between residents with different lifestyles are not limited to residents from different ethnic or cultural backgrounds. Tensions also arise between residents of different ages, different household types and with different working schedules. Cultural difference is but one of many factors that can contribute to tensions in apartment buildings.

However, strata managers also commented that sometimes new arrivals’ lack of English and lack of familiarity with Australian regulations had prevented them from fully participating in their building by, for example, joining strata committees or attending or speaking at meetings. Sometimes new arrivals were not even aware of basics such as the need to pay strata levies. Quite possibly that’s a result of strata rules and regulations not having been adequately explained to them.

Australian strata regulations and bylaws reflect a particular understanding of what it means to own or live in an apartment. Obligations and opportunities here – for example, the right to vote on motions at meetings – may look very different in other countries.

Apartment residents, strata committees and strata managers are finding that they need to adapt to the reality of their culturally diverse communities. After all, multiculturalism is about acknowledging and respecting difference.

Fostering cohesion

As we have previously discussed, more inclusive practices – such as translating documents and meeting discussions, conducting audits and surveys of building residents, and providing a range of opportunities for participation – will benefit all residents and owners, regardless of their background.

While multicultural apartment blocks may pose challenges, they also offer opportunities for residents to enjoy the richness of a diverse and cosmopolitan environment. This is one of the enormous attractions of urban life. For many apartment residents, it’s available on an everyday level.

![]() With growing numbers of urban residents living in apartment buildings that are also culturally diverse, more efforts to foster co-operation and understanding are vital for realising the potential of these urban spaces to become productive hubs of everyday multiculturalism in Australia.

With growing numbers of urban residents living in apartment buildings that are also culturally diverse, more efforts to foster co-operation and understanding are vital for realising the potential of these urban spaces to become productive hubs of everyday multiculturalism in Australia.

Christina Ho, Senior Lecturer & Discipline Coordinator, Social & Political Sciences, University of Technology Sydney; Edgar Liu, Research Fellow at City Futures Research Centre, UNSW, and Hazel Easthope, Senior Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles