Sydney is awash with construction activity – new motorways, light rail and the Metro project are all part of an infrastructure deluge. And as New South Wales voters head to the polls, the two major parties keep raining promises on electorates of ever-larger, ever-faster transport projects.

But with early voting now open, it’s time to take stock. And Grattan Institute has tallied the numbers to help make sense of it all.

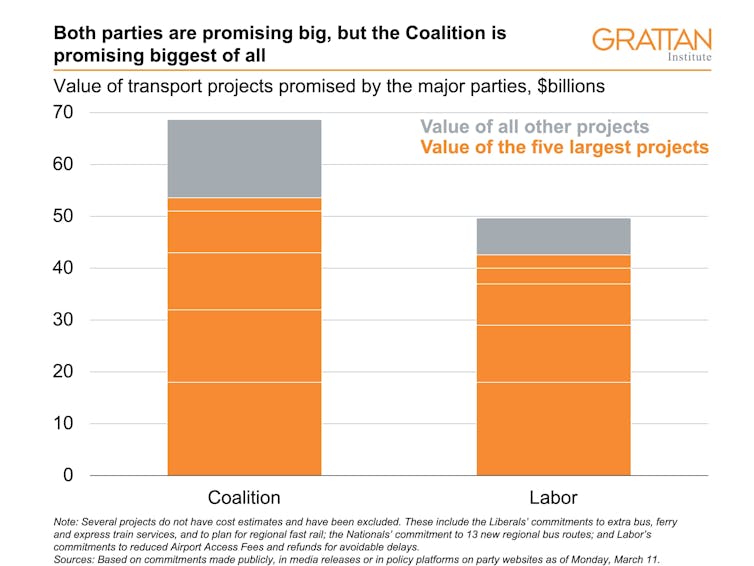

First, the total cost: Labor is promising about A$50 billion of transport projects, and the Coalition about A$70 billion. And the five largest projects on each side together account for more than three-quarters of the total cost. This matters – the bigger the project, the more likely it’ll go over budget, and in a big way.

Read more: WestConnex audit offers another $17b lesson in how not to fund infrastructure

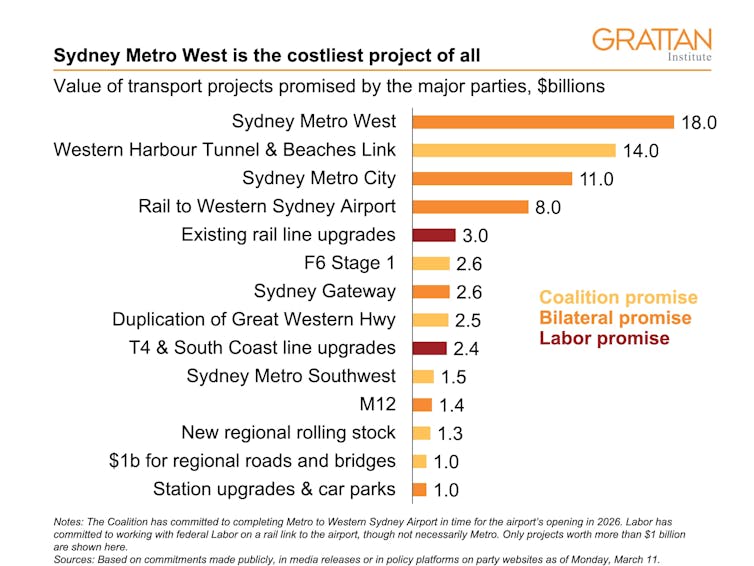

So far, 14 projects have been announced with price tags in the billions of dollars. Each A$1 billion equates to around A$125 from every person in NSW.

How different are the party platforms?

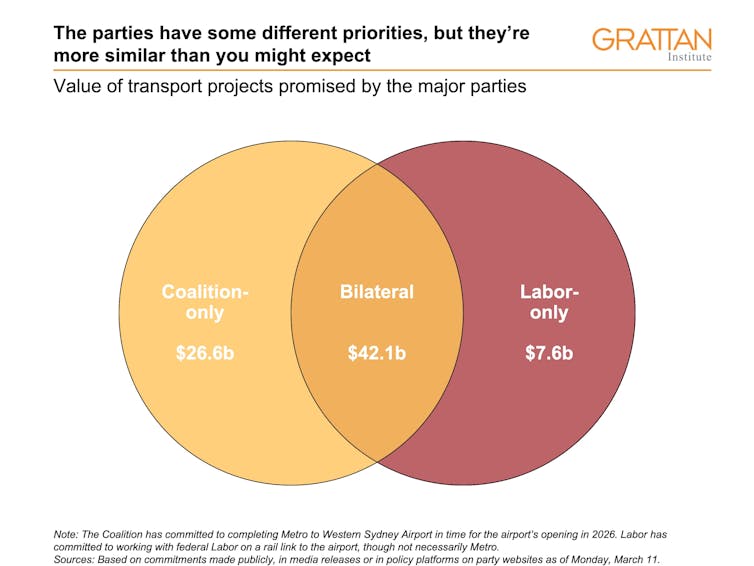

A striking difference between this election and the Victorian election last November is how much the major parties actually agree on. Both support three of the four largest projects. Voters take note: no matter who wins, you can expect to pay for most of the transport infrastructure promises now on offer.

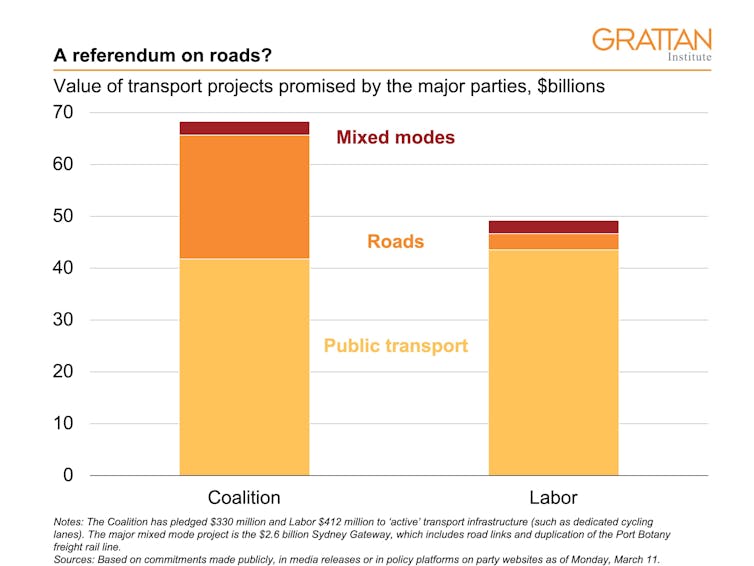

The major difference is in the parties’ positions on roads – especially toll roads. The Coalition is backing the A$14 billion Western Harbour Tunnel & Beaches Link and the A$2.6 billion F6; Labor is promising to scrap them.

Before he resigned as state Labor leader last November, Luke Foley declared that Labor would “unashamedly prioritise public transport over toll roads”. His successor, Michael Daley, appears to have held the course.

The bulk of public transport spending by both sides will be on rail, nearly all of it in Sydney. An exception is the Liberals’ plan for regional fast rail. Sound familiar? Just a few months ago, the then leader of the Victorian Liberals, Matthew Guy, tried to woo voters with a similar promise.

Unlike their southern counterparts, the Berejiklian government is not taking an actual plan to the election, just a commitment to plan. It’s a move they might’ve learned from Victorian Labor Premier Daniel Andrews and his promised A$50 billion rail loop. The NSW Liberals have not provided any cost estimates for fast rail, so Grattan Institute has excluded it from these charts; safe to say, including it would make the Coalition’s total spending promises even more enormous.

Read more: How much will voters pay for an early Christmas? Eight charts that explain Victoria’s transport election

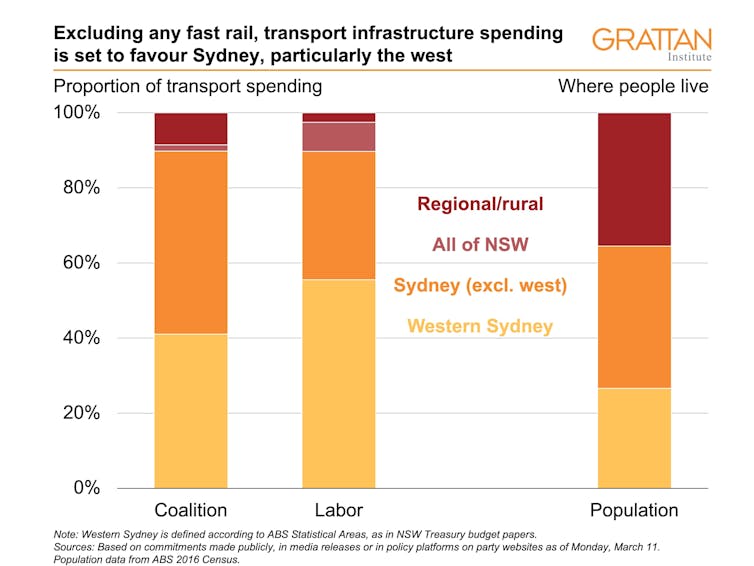

The coming transport infrastructure wave is heavily focused on Sydney. Both parties are set to pour cash into western Sydney, a clear battleground. It’s not surprising that regional NSW gets less of the transport love – voters outside the capital might be more concerned with hospitals and schools than with transport, particularly if they face little congestion.

How well justified are these projects?

Election campaigns can feel like birthday parties, with politicians bestowing gifts upon voters. But these gifts are largely paid for by the taxpayer, or by motorists in the case of tollways. Big infrastructure doesn’t come with a gift receipt; voters need to know in advance whether these projects’ benefits outweigh the costs.

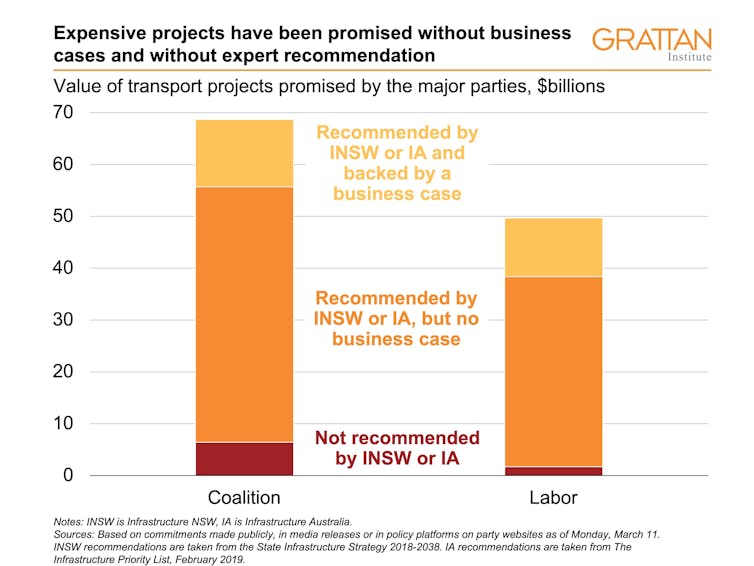

Infrastructure NSW and Infrastructure Australia are two independent bodies that can identify worthy projects and assess business cases. Only two major projects have a tick of approval from either of those bodies – Sydney Metro (City and Southwest sections), and Stage 1 of the F6.

The Coalition supports both of these, whereas Labor supports only the City section of Sydney Metro. It is unclear why Labor would walk away from projects with established net benefits to the community.

Voters should be concerned that the other promised infrastructure is either not recommended or lacks business cases.

It can be difficult for an opposition to complete a business case, given it doesn’t have access to department resources. The government has no such excuse. Making promises without first scrutinising them forces voters to make risky decisions. Grattan Institute research shows that cost overruns were 23 percent higher for projects announced close to an election.

Read more: Spectacular cost blowouts show need to keep governments honest on transport

Reforms promise a better way

Governments should do their due diligence before election time. Fortunately, there are signs of improvement on this score.

Labor is promising to introduce public planning inquiries on projects worth more than A$1 billion. This should help ensure business cases are completed, independently assessed and accessible to the public before projects are approved. When infrastructure is so costly and, at times, controversial, it’s very worthwhile to strive for community support and bipartisanship.

And Labor promises a new level of transparency in how government operates, by bringing in the independent pricing regulator, IPART, and the Auditor-General to shine a light on toll road contracts.

Labor also promises to strengthen the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) so that it runs all year round, not just before elections. Much like the Victorian PBO, this would enable minor parties to have their policies costed as well.

With 30 percent of voters planning to cast their ballots early this election, the PBO should also be required to publish budget impact statements two weeks before the election, not five days. This would help early voters to make informed decisions, as well as raising public suspicion about any policy announced in the fortnight before election day, too late for costing.

Recent experience suggests that promising splashy projects with big price tags can be very effective at election time. With more accountability and better processes, voters mightn’t be so easily swept off their feet.

Read more: We hardly ever trust big transport announcements – here's how politicians get it right

Marion Terrill, Transport and Cities Program Director, Grattan Institute and James Ha, Graduate Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Wikimedia Commons