Ryan Remiorz/AP/AAP

Ryan Remiorz/AP/AAP

The coronavirus has been escaping with distressing frequency from quarantine hotels, threatening serious outbreaks. To make things worse, multiple variants of the virus, possibly more infectious and deadly, have recently been detected.

This accentuates the need for robust hotel quarantine, especially in countries like Australia that have controlled community transmission.

Read more: Perth is the latest city to suffer a COVID quarantine breach. Why does this keep happening?

While the hotel quarantine system has received wide attention, relatively few people have had the opportunity to experience and observe it first hand. Even fewer have been able to compare with other regions handling similar challenges. I happen to have needed to travel overseas and thus experienced quarantine in several places over the past months.

Based on my experience as an academic in architecture, I share some thoughts and observations here on how the design or redesign of buildings, infrastructure and cities can help people overcome the health challenges created by COVID-19.

Our buildings and cities were not designed to handle such extraordinary situations as this pandemic. One consequence is their design has often made the need to touch surfaces unavoidable.

Read more: How worried should I be about news the coronavirus survives on surfaces for up to 28 days?

Take lifts, for example

Some of the most frequently touched surfaces in buildings are the buttons in lifts. In some buildings in China, plastic wrap is used to cover the buttons and a sticker showing the time and date of last disinfection is attached nearby. Other buildings provide tissues for people to use as disposable finger covers.

In quarantine hotels, this procedure is even more carefully managed. Staff help guests by pressing the button. This small touch area needs frequent cleaning, which calls for extra human resources.

Various strategies used in public lifts. Above left, in Melbourne; above right and below left, in Kunming; below right, in Guangzhou. Photos: Mengbi Li (top row and bottom left), Fei Zhou (bottom right)

Various strategies used in public lifts. Above left, in Melbourne; above right and below left, in Kunming; below right, in Guangzhou. Photos: Mengbi Li (top row and bottom left), Fei Zhou (bottom right)

At Baiyunshan airport in Guangzhou, I used a lift with touch-free buttons. The keypad had infrared sensors installed next to the usual button. With just a wave of their finger over the touch-free button, users can select their destination.

A lift with infrared sensors at Baiyunshan airport in Guangzhou. Photo: Xiao Xu

A lift with infrared sensors at Baiyunshan airport in Guangzhou (video by Xiao Xu)

A lift with infrared sensors at Baiyunshan airport in Guangzhou. Photo: Xiao Xu

A lift with infrared sensors at Baiyunshan airport in Guangzhou (video by Xiao Xu)

Another mode free of physical screens features numbers displayed in a front-projected holographic display. A sensor detects the movement of pressing a button in the air to activate the lift.

A front-projected holographic display means there’s no need to physically touch the buttons in this lift.

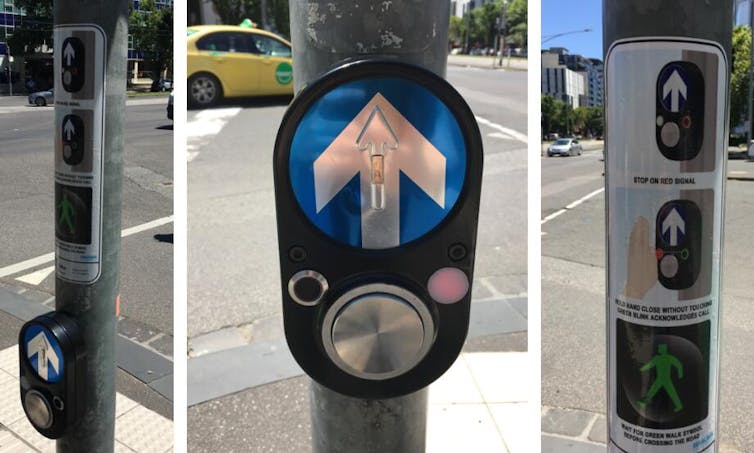

This technology is not out of our reach. In response to the pandemic, authorities in Melbourne and Sydney have trialled touch-free buttons using infrared technology at pedestrian crossings.

A pedestrian crossing signal with an infrared sensor in Melbourne. Photo: Mengbi Li, Author provided

A pedestrian crossing signal with an infrared sensor in Melbourne. Photo: Mengbi Li, Author provided

One concern about touch-free buttons is the challenge they present to the visually impaired. Currently, a push-button is placed next to the infrared sensor. An alternative for people who need assistance would be to use gesture or voice commands. Other concerns include reliability and vandal-proofing.

Another sensitive touch spot is the toilet. The airport toilets I visited in Australia, China and Singapore are equipped with touch-free features to activate the flush, tap, soap dispenser and hand dryer. However, the doors and locks cannot function without touch. Touch-free sensors or foot pedals would probably help.

Alternatively, new materials or coatings like antimicrobial polymers could be applied in areas where touch is unavoidable. Of course, care must be taken to ensure the antiviral potency is both reliable and people-friendly.

Read more: Automatic doors: the simple technology that could help stop coronavirus spreading

Design solutions don’t have to be high-tech

A touch-free hand sanitiser dispenser in Melbourne. Photo: Mengbi Li

A touch-free hand sanitiser dispenser in Melbourne. Photo: Mengbi Li

Interestingly, touch-free public spaces do not always rely on advanced materials or sophisticated technology. In a Melbourne quarantine hotel, I noticed several bollards with foot pedals being used as hand sanitiser dispensers. These are designed to function mechanically and require no power connections.

Instead of a simple stainless steel bollard, this dispenser could be further reimagined as an artistic sculpture integrating the building’s signage at the entrance. Elsewhere, this design could be incorporated into litter bins along the streets.

Usually, for architectural design, circulation patterns are analysed to see how people reach each space and establish the relationships between different areas. For safety purposes, exits are checked to ensure people can evacuate in a timely way. To prepare for future pandemics, these studies could add analysis of touch points in both pandemic and non-pandemic periods.

The shared challenge posed by the pandemic has prompted some innovative ideas. For example, physical reminders to keep a social distance have variously involved using carpet tiles, mowed or trimmed landscape patterns, furniture arrangements, temporary structures and pavements or stickers.

Other solutions involve applying modular construction from well-equipped containers to create emergency hospitals or mobile testing stations.

Read more: Hospital beds and coronavirus test centres are needed fast. Here's an Australian-designed solution

Plug-in intensive care units created from a shipping container were installed at a temporary hospital set up in Turin, northern Italy. Max Tomasinelli/Carlo Ratti Associati

Plug-in intensive care units created from a shipping container were installed at a temporary hospital set up in Turin, northern Italy. Max Tomasinelli/Carlo Ratti Associati

From touch-free public spaces to designing for social distance and modular construction, there are still many ways the design or redesign of our buildings and cities can help to protect the public. Good design is particularly important to protect those in high-risk environments, such as workers and senior citizens in health care and aged care.

Read more: Poor ventilation may be adding to nursing homes' COVID-19 risks

The Six Feet Office uses design to enable social distancing.

As necessity is the mother of invention, there is nothing like a period of stress to stimulate creativity, industry and innovation.

Mengbi Li, Lecturer in Built Environment (Architecture), First Year College and Research Fellow, ISILC, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.