“Le beau est toujours bizarre” is a quote from French poet Charles Baudelaire that can be translated to “beauty is always bizarre”. This is the DNA of mimetic architecture, when buildings and other structures are given a blend of eccentricity, follies and unusual shapes – just because.

In Australia, mimetic architecture – also called novelty architecture – has taken many shapes and forms.

A few classical examples – if mimetic architecture can be anything but – are the National Museum of Australia in Canberra and to a lesser extent, the Sydney Opera House.

Designed by architect Howard Raggatt and his team, the museum's design is inspired by the natural landscape, incorporating forms and patterns that mimic the environment, while the Opera House’s iconic sail-like shells were inspired by natural forms and have been interpreted as mimicking the sails of ships or the curves of natural elements.

But mimetic architecture isn’t always about impersonating nature. Sometimes, it can be about impersonating architecture itself.

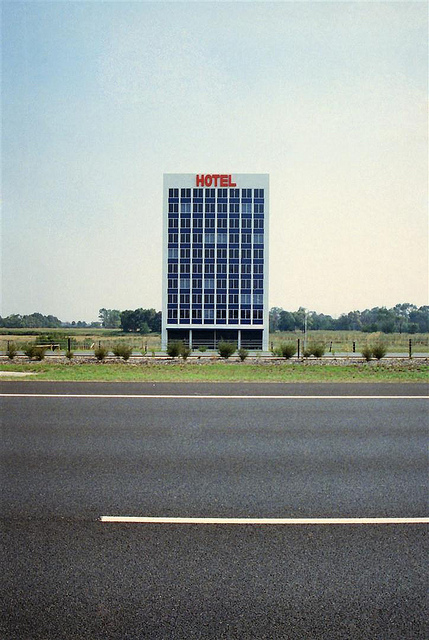

Hotel by Callum Morton on Eastlink.

An example of this: Hotel by Callum Morton on Eastlink between Greens Road and Bangholme Road, in Victoria.

“Hotel is a large-scale model of a high rise hotel. It will sit alongside EastLink in an open field. Hotel is effectively a giant folly,” says Morton about his installation.

“Motorists will view it from the car as an actual hotel and perhaps over time as a strangely de-scaled prop that has escaped the theme park or film set.”

A hotel, but not in the figurative way.

For Morton, Hotel is certainly mimicking a hotel but only because the sign says Hotel.

“Otherwise it’s just mimicking a generic building and certainly not a figurative one. The difference with Hotel is that it approximates a generic thing that might otherwise appear on the side of the road and so, despite it appearing like a model or cartoon, it has many people thinking it is the thing it purports to be and so often goes unnoticed,” he says.

“That’s because of the sign and the lights that come on at dusk. Because of this it activates other narratives. You can’t simple dismiss it as a fake thing so easily."

However, despite its differences, Hotel is in that family of buildings and roadside objects according to Morton.

“I certainly love the literalism of the Big Pineapple, The Big Duck Building, the Big Prawn in Ballina and so on. They are kitsch but they’re ingenious as well – the fabrication or simulation of objects at large scale is great and the way they get it wrong too lends them a glorious charm.

“As a child on the way to Aireys Inlet in the car we always went past the giant Lemonade Bottle outside Geelong that was a kids slide. That stayed with me.”

Hotel at dusk.

On the genesis of Hotel, Morton says it had long gestation period.

“I was known early in my career for making scale models of specific architecture and animating them with light and sound that was often humorous or visceral,” he says.

“At some point I thought it would be good to take these models and blow them up to re-enter the world as actual objects that had a strange otherworldly presence. Hotel is essentially that a model that is enlarged not a building that has been shrunk.”

Mimetic architecture not only recoups buildings, but sculptures as well, sculptures of ordinary items scaled to building size, often representing local animals.

Supersized eagle by Tank Art and Steve Tobin.

Literally larger than life, Tank Art and Steve Tobin’s sculptures are an ode to Australian wilderness.

Their humongous steel animals are designed, crafted and assembled at the heart of the Strathbogie Shire, Victoria.

“The reason we replicate birds and animals as that nature has already done the art for us, the reason we make it bigger is to highlight what beautiful things we have right under our noses and how unique Australian wildlife really is,” Tobin says.