Energy efficiency in Australian homes is an increasingly hot topic. Spiralling power bills and the growing problem of energy poverty are set against a backdrop of falling housing affordability, contested carbon commitments and energy security concerns.

Most people agree we need modern, comfortable, eco-efficient homes. This article is not about the relatively few, new, demonstration “eco-homes” dotted around Australia. It is about the rest of our housing.

These mainly ageing homes might have had energy efficiency improvements done over the years, but invariably are in need of upgrading to meet modern standards of efficiency and comfort.

Read more: Thinking about a sustainable retrofit? Here are three things to consider

Since 2006, all new-build housing must meet higher energy efficiency standards. But we add only around 1% to the new housing stock each year.

Policies to improve energy efficiency in the other 99% are more fragmented. The focus is almost entirely on market-based incentives to “retrofit”. By this we mean material upgrades to improve housing energy and carbon performance.

THE TRANSITION HAS BEGUN

Nevertheless, a major retrofit transition is under way. In the last decade, around one in five Australian households has installed solar panels. More than three million upgrades have been carried out through the Victorian Energy Efficiency Target (now Victorian Energy Upgrades) initiative.

These impressive numbers describe a nationally important intervention. But does this mean we will soon all get to live in eco-homes, rather than just a lucky few?

Current retrofitting activity has occurred unevenly and may contribute to longer-term inequalities.

For example, rebates for deeper retrofits often are more accessible to the better-off home owners. They have matching cash and also rights to make major upgrades (as opposed to renters). This entrenches the existing reality that low-income renters tend to live in less energy-efficient homes.

Similarly, in the UK, retrofit incentives haven’t always successfully targeted those most in need. The distribution of costs has contributed to pushing up energy prices for those already in energy poverty. In Australia, up to 20% of households were already in energy poverty before recent price rises.

Thus, if poorly targeted and funded, energy efficiency initiatives might make existing dynamics worse and add to the cumulative vulnerabilities of housing affordability stress.

Read more: Housing stress and energy poverty – a deadly mix?

KEEPING TRACK OF HOW HOMES RATE

We cannot effectively monitor this. This is because Australia has no robust, longitudinal national database of property condition. There is no established, widespread practice of property owners obtaining property condition reports that set out the energy-efficiency performance and the most viable improvements that could be made.

This means we do not have a systematic way of knowing what we should do next to our homes, even if we are lucky enough to own them and have some cash available, as well as the time and motivation to retrofit.

To the rescue, at least in Victoria, is the new Victorian Residential Efficiency Scorecard. This is an advance on previous attempts (as in the ACT and Queensland) to develop comparable assessments of the energy efficiency and comfort levels of your home. Although voluntary, the scorecard will provide owners with a report on their home and a list of measures they can consider to transform it “eco-homewards”.

So, is the scorecard the answer to our problems? Will it bring forward the date when we can all live in comfy eco-homes? It will certainly help.

The European Union has had a mandatory system since the Energy Performance in Buildings Directive. The evidence suggests this has raised awareness of energy efficiency by literally putting labels of buildings in your face when you are deciding where to buy. It’s much like Australians have become used to energy efficiency labels on fridges and other appliances. However, evidence of this awareness actually leading to upgrade activity is more mixed and, in some cases, disappointing.\

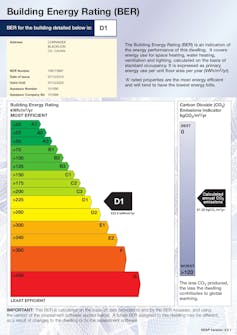

Since 2010, the European Union has mandated ratings of how a building performs for energy efficiency and CO₂ emissions. Image: The Conversation

In short, we need the scorecard and should welcome it. However, we also need a set of other measures if we are to make the transformations to match our national policy objectives and our desires for a comfy eco-home.

WHAT ELSE NEEDS TO BE DONE?

The research agenda is also shifting to explore the social and equity dimensions of the retrofit transition.

In areas where installation work on energy-efficiency/low-carbon retrofits is increasing, how is this working in households? Who makes decisions? How do they decide and with what resources? What or who do they call upon? And, more broadly, what are the positive or problematic consequences for equity and, therefore, for policy?

Read more: What about the people missing out on renewables? Here's what planners can do about energy justice

Emerging retrofit technologies and behaviours have broader social and economic contexts. This means we need to understand the wider meanings and practices of homemaking, the uneven social and income structures of households, and the home improvement service industry.

While the retrofit transition is arguably under way, its consequences and dynamics are still largely unknown. We need to refocus away from simply counting solar systems towards understanding retrofitting better. This depends on understanding both the households that are retrofitting their homes and the industries and organisations that supply them.

To get energy policies right and overcome energy poverty, we need to bring together studies and initiatives in material consumption, sustainability and social justice.

To get energy policies right and overcome energy poverty, we need to bring together studies and initiatives in material consumption, sustainability and social justice.

Ralph Horne, Deputy Pro Vice Chancellor, Research & Innovation; Director of UNGC Cities Programme; Professor, RMIT University; Emma Baker, Associate Professor, School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Adelaide; Francisco Azpitarte, Ronald Henderson Research Fellow Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research & Brotherhood of St Laurence, University of Melbourne; Gordon Walker, Professor at the DEMAND Centre and Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University; Nicola Willand, Research Consultant, Sustainable Building Innovation Laboratory, RMIT University, and Trivess Moore, Research Fellow, RMIT University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.