Almost 90 percent of New Zealand’s population is urbanised. Getting policy right for towns and cities will be crucial for the new Labour-led coalition government’s ambitious policy agenda to transition to a low-emissions economy while addressing major social issues such as unaffordable housing, inequality and poverty.

Central governments and cities aren’t always on the same page when it comes to policy priorities. An OECD report released at the recent World Urban Forum showed that, globally, urban areas aren’t well served by national-level policies.

This is a timely issue for New Zealand. Currently, the only national urban policy is the 2016 policy on development capacity for future growth. The issues facing urban areas go far beyond land use planning and growth management.

Where do the central government come in?

New Zealand’s former government had a somewhat dysfunctional relationship with local authorities. Across nine years in power, the National-led government found itself entangled in controversies over major transport projects, representation for Māori, the Auckland housing crisis, and the risk of zombie towns.

Many countries don’t have a coherent framework for how they want urban areas to develop. Should the most productive areas be favoured? Should cities actively compete with one another? Should there be redistribution to struggling regions?

The global urban agenda spearheaded by UN Habitat is calling to leave no city behind. New Zealand can learn from two key aspects of this agenda. First, policies should cater for all urban areas, not just major cities. Second, urban areas are facing new challenges related to climate change and inequality, and need policies that are both innovative and inclusive.

Read more: What can the New Urban Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals do for cities?

Labour’s policy agenda: impacts on towns and cities

Labour’s 100-day plan introduced measures on climate change and housing. It committed to the introduction of zero-carbon legislation, halted the sale of state housing, passed the Healthy Homes bill, and proposed a housing commission. It also introduced legislation to extend the bright line test, which determines whether tax has to be paid on profit in sales of residential property, from two to five years. Plans to scale up house building will improve supply, but the government opted to delay the possibility of a capital gains tax, with no reform before 2021.

Mere contemplation of a capital gains tax is seen as politically impossible. However, the government cannot maintain the status quo without paying a hefty political price. A large share of the population is shut out from home ownership without substantial parental support and is being forced into insecure rental markets.

A capital gains tax alone cannot bring down house prices, but it will make speculative investment less lucrative. We can learn from Australia that the tax design matters.

A shift to sustainable urban transport

Labour’s transport policy is a big change from National’s motorway-heavy investment program. It promises balanced investment across roads and public transport.

Going forward, this will mean better quality and more frequent public transport services. Regional rail upgrades are on the agenda, supported by the Provincial Growth Fund. It also leaves the future of several major projects is in question, including Auckland’s $1.85 billion East West Link motorway project. This is under review due to excessive costs - it would have been the most expensive road in the world - and unclear benefits.

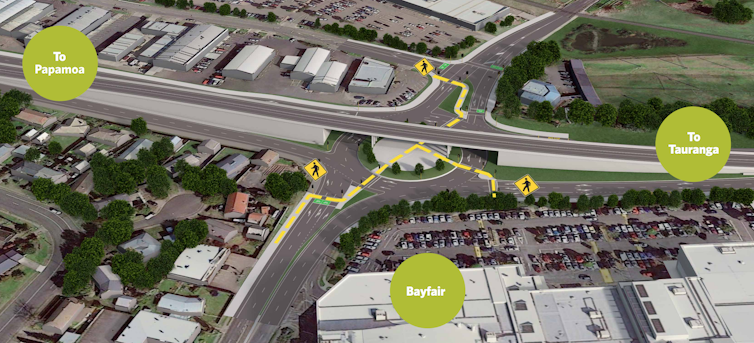

It remains to be seen whether other “legacy projects” that reinforce our dependence on cars will be allowed to continue. The $120 million Baypark to Bayfair link is a 1km flyover for Mount Maunganui’s main arterial route. The project generates only four minutes’ travel-time saving for drivers, with no public transport provisions and major impacts on the local community.

Baypark-to-Bayfair link – improving mobility or reinforcing car dependence? Image: NZTA

No town or city left behind

The New Urban Agenda offers two useful directions for government policy. First, urban policy is for cities of all sizes. It is not all about Auckland. Auckland’s problems – unaffordable housing, traffic congestion and social inequality – are significant. However, the city receives much government and media attention, biasing national policy and provoking public debate that pits urban and regional areas against each other. Second, more innovative and inclusive approaches to policy are needed to solve the new challenges for urban areas.

As shown below, Auckland is New Zealand’s largest urban area by far, and is described as the country’s economic powerhouse.

However, the collective population of small and medium-sized cities, shown in the chart below, outnumbers Auckland. These areas must be better served by national-level policies.

To do this, policy should go beyond the usual big-city issues of traffic congestion and growth management. Climate change mitigation require a radical shift in transport for cities of all sizes to reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Climate change is also a big risk for coastal urban areas and adaptation to extreme weather and sea level rise is critical.

Urban sustainability isn’t just about what happens in the local area, and should consider the wider impacts. Urban areas require massive transfers of natural resources and nutrients from other areas to provide water, energy, and food. Better sustainability metrics can ensure that cities are not dependent on unsustainable practices outside the city boundaries.

Homelessness and overcrowding in Auckland receive the most media attention but Gisborne and Northland have similar rates to Auckland.

The Housing Infrastructure Fund initiated by the former government meets short-term needs, but adds to local government debt and shifts a bigger financial burden to future generations. As the OECD stresses, the “grow now, pay later approach is not an option because it bears a lot of costs on society and the environment”.

New directions for urban policy: innovative, inclusive, indigenous

The challenges facing cities require inclusive policy solutions. Inclusive growth is now on the agenda for mayors across the world. Movements for cities to become age-friendly, women-led and racially equitable are demonstrating how policy can create better outcomes for everyone in cities.

Innovative policies often look to learn from cities overseas, however, drawing from local and indigenous knowledge is also crucial for New Zealand. Urban planning is mostly based on Western paradigms, but indigenous knowledge must be prioritised to be inclusive of Māori values. For example, the recent recognition of the legal personhood of the Whanganui River acknowledged the environment’s status in te ao Māori. Policies for housing and land use could go further to prioritise indigenous knowledge.

Read more: How can we meaningfully recognise cities as Indigenous places?

Māori knowledge can address cross-cutting issues, with holistic understandings such as kaitiakitanga (guardianship and conservation) and ki uta ki tai (interconnected resources and ecosystems). Decision-making frameworks like the Mauri model integrate indigenous knowledge into engineering design and investment planning.

New Zealand’s new government has a big task ahead to tackle climate action, housing and environmental sustainability for towns and cities. To achieve this, policies should take heed of the global urban agenda – catering for areas of all sizes and actively shaping inclusive towns and cities that allow New Zealand’s diverse urban population to thrive.

New Zealand’s new government has a big task ahead to tackle climate action, housing and environmental sustainability for towns and cities. To achieve this, policies should take heed of the global urban agenda – catering for areas of all sizes and actively shaping inclusive towns and cities that allow New Zealand’s diverse urban population to thrive.

Jenny McArthur, Postdoctoral Research Associate in Urban Governance (Infrastructure Governance, Policy and Planning), UCL

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.