The Northern Hemisphere is currently suffering an unprecedented heatwave. In Japan, more than 100 people have died and tens of thousands more are in hospital due to heat-related illness.

Tokyo, which is hosting the 2020 Olympics, has for the first time registered temperatures over 40℃. This is raising concerns about the city’s viability to stage long-distance outdoor events such as the marathon and the endurance walk in similar conditions. The government has even discussed introducing daylight saving so marathon runners can start at 5 or 6 am.

One of the authors of this article, Makoto Yokohari and colleagues, recently published a paper that predicted the heat stresses on the athletes’ bodies during the race. They showed even at the very start of the race, runners will be exposed to extremely dangerous temperatures, which will only get more extreme as they move along the course.

So, what can Tokyo do to lessen the risk of heatstroke for both athletes and spectators of the 2020 Olympics?

Read more: It's a savage summer in the Northern Hemisphere – and climate change is slashing the odds of more heatwaves

How hot will it be?

Tokyo has hosted the Olympics before, in 1964, but these games were held in October. Following a tradition of three decades, the summer Olympics will now be held from July 24 to August 9. And there’s a good chance of very high temperatures during this time in 2020.

The ability for the human body to allow evaporation is a critical part of coping with heat. One way sports physiologists measure heat is by using the wet bulb-globe temperature. This temperature reading combines heat and humidity. If the humidity is high, less water evaporates so the recorded temperature is higher. Prior research has shown risk of heat stroke increases dramatically if the wet bulb-globe temperature exceeds 28℃.

Read more: Health Check: how can extreme heat lead to death?

The chances of this occurring during the Tokyo marathon are high. In Tokyo, the average maximum daily temperature is around 30℃ and the average relative humidity over 70 percent in July and August. The chosen marathon course also includes a number of areas that put athletes and spectators at risk, such as the courtyard of the Imperial Palace, a wide expanse of shadeless asphalt the runners are expected to cross twice – the second time after having run 35km.

The Tokyo Olympics marathon track is designed to go past some of the city’s signature sights, such as the Imperial Palace. from shutterstock.com

The course determination was based less on the athlete’s welfare and more on the attractiveness of Tokyo’s touristic locations. As Lord Sebastian Coe, head of the International Association of Athletics Federations noted:

The marathon course is a growing highlight of the athletics program with imaginative courses that show off the best of cities, are challenging for athletes and are fan friendly.

The team’s paper calculated the metabolism of the runners and the expected stresses on the human body during the race. The model they used considers air temperature, humidity, likely energy absorption of heat from the surroundings and the heat generated from running.

The model showed that extremely dangerous temperatures will be present at the start of the race. On a stretch of the east-west highway, the athletes will run for a mile towards the sun. The high values of solar radiation and road surface temperatures means this section is rated as extremely dangerous.

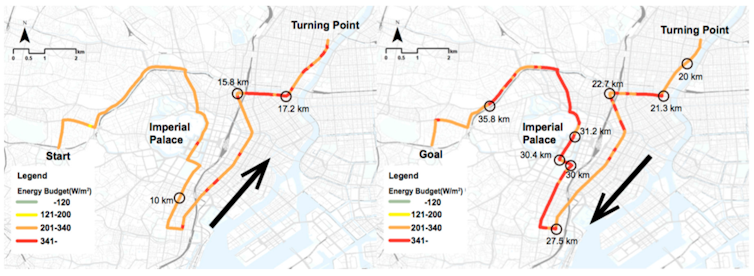

The maps below illustrate the energy budget, which is the heat athlete’s bodies are projected to absorb during the race if it were to go ahead as planned, starting at 7:30am on August 9. The ideal number for a marathon should be as low as possible, and the higher the number climbs, the more the body is absorbing heat.

What can the city do?

Projected energy budget for the runners if race is on August 9 at 7.30am. Author provided

For the runners, some options like changing the side of the road on which they run can be considered. Overhead shading is possible but obviously costly. Water spraying is an option but is not very effective in humid conditions. Street trees for shading can double their height from 2.5-5m but this can take five years. Leaving more greenery in Tokyo would certainly be a good legacy but with two years to go, they won’t be ready in time.

For the spectators, one suggestion is to ask retailers, restaurants and businesses along the course to voluntarily open their stores and offices to those who feel sick, allowing them to stay in an air-conditioned room and provide them with a water bottle and a wet towel to cool them down. A network of such businesses might be the key.

Read more: We need to 'climate-proof' our sports stadiums

More radical suggestions include changing the season to late October or early November. But the decision has been ruled out by the organisers, mainly as it falls out of line with the prime time US TV schedule. Changing the location of outdoor sports to the northern Island of Hokkaido, or the highlands in Nagano or Yamanashi around 150-250km from Tokyo, is another idea. And the most drastic is to move the race time, so it starts at 2am and finishes around 5am.

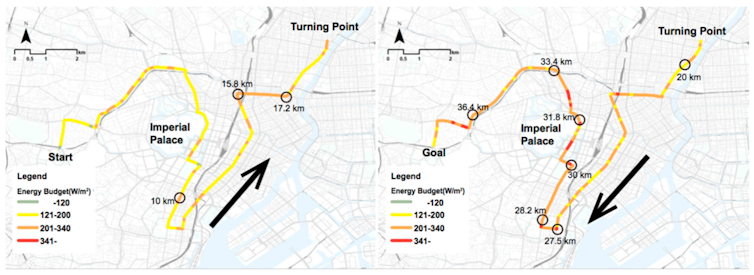

The team’s projections, shown in the map below, illustrate the drop in dangerous heat levels if the race is held later, on August 25 at 6:30am.

Projected energy budget for the runners if the race is held later, on August 25 at 6.30am. Author provided

The Olympic Organising Committee Tokyo 2020’s Sustainability Plan and Guiding Principle includes the aim to bring nature into the city. Part of its proposed plan is to coat the road with a resin that will reflect the heat. A lighter road surface can certainly help and this is something cities in Australia are experimenting with. It is unknown whether the shading and painting will be enough to cool the course.

Legend has it the original marathon runner the Greek messenger Pheidippides died on reaching the finishing line. Let’s hope the Tokyo 2020 Olympics isn’t a historical re-enactment of that event.

The Olympic marathon in the 1965 documentary Tōkyō Orinpikku. In those days athletes were amateurs - some ran barefoot and they stopped to have a drink.

Marco Amati, Associate Professor of International Planning, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University and Makoto Yokohari, Professor, Division of Environmental Studies, University of Tokyo

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.