Elon Musk has an ‘innovation equation’: time + people + materials = the ability to innovate. Love or hate him, the prolific sharing of this calculation speaks to the enormous value the ability to innovate holds today. Ideas, and the process of implementing them, propel society forward.

As a result, innovation is heavily invested in worldwide. 2022’s Global Innovation Index (GII) shows a boom in endowments[1], with global spending reaching a record high of almost 1.7 trillion dollars[2]. These investments mark the pursuit, support and nurturing of innovation as one of the biggest priorities of our time.

Enter the ‘innovation space’ – purpose-built for innovation and promising to connect education, science and research with industry, governments, and communities. Though their scale can vary considerably, some spanning continents and others contained within single rooms, all are built to nurture ideas.

The success of an innovation space is entwined with understanding how they work at specific scales: District, Precinct, Hubs, Building and 1:1. The best results happen when designers pair certain questions with each scale at the initial design stages. These questions are:

5 km ² + Districts

Closing the distance: “What are the unique shared aims and objectives?”

When considered at their largest scale, one of the most important things for an innovation space to establish is a common goal, meaning designers must ask “what are the unique shared aims and objectives?”. The answer will inform a clear vision that provides a strong basis for briefing and engagement. With everyone focusing on the immense potential of the whole district, this shared concept will provide a cohesive framework able to contend with the sprawling distances of this scale.

Driven by the vision ‘to be a transformative and collaborative place of excellence solving global challenges to enhance and nurture lifelong health’[3], the Randwick Health and Innovation Precinct (RHIP) incorporates Sydney Children’s Hospital, Royal Hospital for Women, Lowe Institute, and the University of NSW. Clearly defined, these shared aims and objectives provide strong direction and incentive to expand innovation beyond its borders, attracting collaborative relationships locally and internationally[4], setting the project apart as an exemplar innovation district.

500,000 m² Precincts

Weaving with space: “How can clustering make these facilities stronger?”

An innovation precinct requires a vison that identifies opportunities to establish meaningful cross disciplinary relationships across the sectors, institutions, and typologies that define the space. Designers must establish the distinctive strengths of each facility and identify how they can be clustered to benefit each other, asking “How can clustering make these facilities stronger?”

Exploring the answer will take an innovation space from a place where buildings are simply located near one another to a place where they actively encourage innovation and creativity through interaction, as was the case with Tonsley Innovation District. Located 10km from Adelaide, Tonsley incorporates government, education, industry, and start-ups within the previously disused Mitsubishi Motors site. Several sectors are entwined here, all clustered around the Main Assembly Building (MAB) which forms the heart of the precinct with core facilities, amenities, and collaboration spaces.

50,000 m ² Hubs

Bound by benefit: “Why choose this space over others?”

An innovation hub can differentiate itself from others through the incorporation of a defining element. The question “why choose this space over others,” helps identify which key industry groups or education facilities that will entice the best innovators to choose that offering over others – uniting them under a mutual benefit.

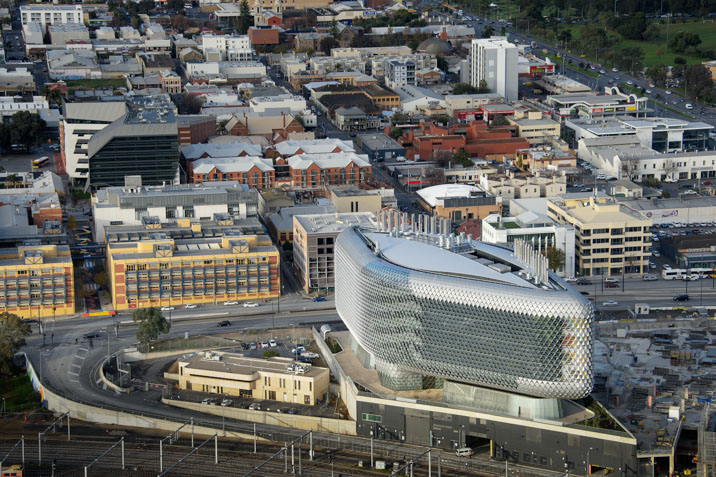

Designers must establish how to provide infrastructure and amenity that supports the established goal of convincing a project’s ideal user to stay, collaborate and contribute early. When combined with exceptional design, hubs can become beacons for ground breaking research – as is the case with South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAMHRI). Located within the Adelaide Biomed Precinct, SAMHRI has an iconic appearance which demands attention. However, it is its agile laboratories, specialist support spaces and core shared facilities that provide the points of difference that attracted multiple research institutions to the wider Adelaide BioMed City.

5000 m ² Buildings

Multi-purpose for purpose: “How can we help ideas to grow?”

Within buildings, individual facilities can be incorporated to develop and grow ideas. At this scale, the innovation space belongs wholly to its users – becoming sanctuaries for creativity and experimentation. As a result, designers must provide space for ideas to be tested, translated, changed, and implemented. We must determine the right level of amenity and adaptability – asking “how can we help ideas to grow?”

The Incubator Building within the Qatar Science and Technology Park provides the flexibility and connectivity desired by industry, research, and start-ups. Located along a main precinct ‘spine’, the building is a central focal point for research that encourages the exploration of ideas. Core and prototyping facilities provide for varied, multi-discipline research, while interstitial plantrooms dotted across the large floor plates allow services to change with minimal disruption as research develops among groups and individuals.

5 m ² 1:1

Researchers face to face, in place: “What’s the glue?”

At an interpersonal scale, designers need to focus on providing the ‘glue’, or connective space, which binds people together – creating an environment that researchers can thrive in. Described as a ‘stickiness’ that attracts diverse collaborators and entices them to contribute to the organically growing ecosystem[5], the question ‘what’s the glue?’ must be considered at the very beginning to be integrated seamlessly with the overall vision and design.

It’s important to remember that the priority is the design of welcoming and inclusive spaces that provide a sense of place and community. Outdoor areas that connect with nature, comfortable spaces to sit with a colleague, or a café with good coffee to chat 1:1 with a researcher from another institution are equally effective in this aim as work and research spaces.

Melbourne Connect provides the ‘glue’ for education, research, and industry via welcoming spaces designed for connection. Combining art with science, Space Gallery encourages easy engagement. Central garden Womin-djerring delivers quiet communal spaces to relax amongst indigenous plants. Cafes, restaurants, and childcare facilities are easily found, while multiple laneways connect with the wider community. Together, these elements supplying the ‘glue’ between incredible innovation facilities – providing binding interstitial space for connection and contemplation.

Micro to macro

When designers and stakeholders investigate the answers to these five questions at the relevant scales, an understanding of spatial requirements emerges. From macro to micro, this allows us to design space for innovation.

This article was written by Woods Bagot's Kerrie Russell and published by Architecture & Design.

Body Images:

- UNSW School of Biomedical Science

- Tonsley Main Assembly Building

- SAMHRI at the Adelaide BioMed Hub

- The Incubator Building within the Qatar Science and Technology Park

- Melbourne Connect

[1] Scientific publications, research and development (R&D) expenditures, international patent filings and venture capital deals all on the rise. Global Innovation Index 2022. https://www.wipo.int/global_innovation_index.

[2] UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), accessed 23/03/2023. https://uis.unesco.org/apps/visualisations/research-and-development-spending

[3] Randwick Health & Innovation Precinct, The future of lifelong health, 2021-2024 Strategy

[4] Randwick Health & Innovation Precinct, The future of lifelong health, 2021-2024 Strategy

[5] PCA, Innovation Precinct Paper.