Matthew Mclaughlin, Author provided

Matthew Mclaughlin, Author provided

Five Australian states and territories are trialling or planning 30km/h speed limits and zones. However, some people question if 30km/h speed limits are actually urgent and necessary, or are instead a so-called “nanny state” policy or revenue-raising activity.

Low-speed streets are about much more than road safety and increasing fine revenue. By building safer streets, governments and cities around the world are creating more liveable cities. The benefits include low crime levels, more physically active citizens, greater social connectedness, increased spending in local businesses and less pollution.

Read more: Getting people more active is key to better health: here are 8 areas for investment

Research shows 30km/h speed limits on local residential streets could reduce the Australian road death toll by 13%. The economic benefit would be about A$3.5 billion every year.

Learning from other countries, it will be important to run public education campaigns to inform communities and opinion leaders. Another key to success is finding a strong political champion of lower speeds in residential streets.

Leadership is needed to counter myths about 30km/h speed limits that are misinforming public and political opinion. As part of the Streets for Life campaign for Global Road Safety Week, the United Nations has busted international myths surrounding 30km/h. In support of domestic demands for 30km/h speed limits, in this article we bust five common myths about 30km/h speed limits in Australia.

Matthew Mclaughlin, Author provided

Matthew Mclaughlin, Author provided

Myth #1: 30km/h limits don’t make a difference

Road trauma is the number one cause of death in school-aged children. More than 1,100 Australians die on our roads each year.

Data source: NSW Transport Metropolitan Roads (2019), Author provided

Data source: NSW Transport Metropolitan Roads (2019), Author provided

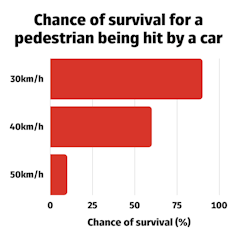

The evidence is very clear: the chance of a pedestrian surviving when hit by a car skyrockets when the car’s speed is reduced. The chance of survival jumps from just 10% at 50km/h to 90% at 30km/h.

Speed is the most common contributor to road trauma – more common than alcohol, drugs and fatigue.

To reduce serious injury risk, 40km/h speed limits aren’t low enough. The chance of survival when hit by a car improves from 60% at 40km/h to 90% at 30km/h. Reducing speed limits to 30km/h in urban areas such as high pedestrian zones, school zones and local traffic areas is urgently needed to reduce deaths and severe injuries.

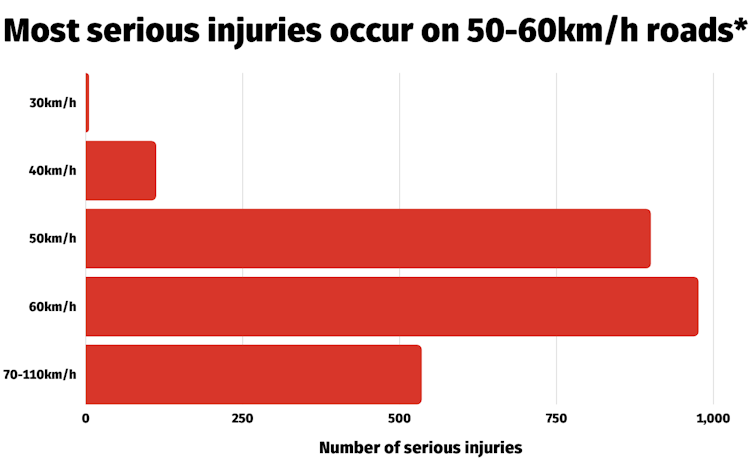

Numbers of serious injuries on New South Wales roads with different speed limits. * Data source: NSW Transport Metropolitan Roads (2019), Author provided

Numbers of serious injuries on New South Wales roads with different speed limits. * Data source: NSW Transport Metropolitan Roads (2019), Author provided

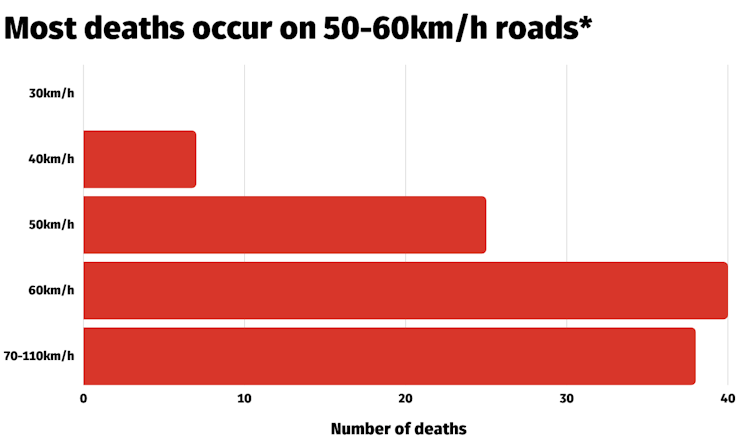

Two-thirds of all crashes in New South Wales occur in metro areas. In these areas, 60% of fatal crashes are on local and collector streets (leading to arterial roads) with 50-60km/h speed limits. To achieve road safety targets and goals of zero road deaths, a 30km/h speed limit is crucial.

Numbers of deaths on New South Wales roads with different speed limits. * Data source: NSW Transport Metropolitan Roads (2019), Author provided

Numbers of deaths on New South Wales roads with different speed limits. * Data source: NSW Transport Metropolitan Roads (2019), Author provided

Read more: Delivery rider deaths highlight need to make streets safer for everyone

Myth #2: 30km/h limits aren’t popular

How supportive would you be of reducing speed limits in neighbourhood streets to help create safer and more liveable streets for people? Well, according to a recent nationally representative poll, about two-thirds of Australians say they want lower speed limits on local streets.

The introduction of 30km/h speed limits around the world shows the popularity of these limits grows rapidly after they take effect and local residents begin to appreciate the multitude of benefits from safer streets.

Read more: London is proposing 20mph speed limits – here's the evidence on their effect on city life

Myth #3: 30km/h limits increase journey times

In urban areas, journey times are affected by more than the speed limit. Key factors include traffic congestion and time spent waiting at traffic signals. One study that considered a reasonably typical 26-minute journey to work calculated the difference between a 50km/h and 30km/h speed limit is less than a minute.

Safer and more liveable streets can decrease our reliance on the private car. By shifting private car trips to active and sustainable forms of transport, such as cycling and walking, we can reduce congestion and improve population and environmental health.

Research from Transport for London has indicated that 20mph (32km/h) zones have no net negative effect on emissions due to smoother driving and less braking.

Read more: Climate explained: does your driving speed make any difference to your car's emissions?

Myth #4: 30km/h limits are anti-motorist

Reduced speed limits are not anti-motorist and are not about banning cars or the ability to drive. A 30km/h limit is a win-win-win for street users, businesses and motorists – and major motoring groups agree.

Lower speed limits can lead to fewer car crashes, in turn reducing insurance costs and time delayed in traffic by those crashes.

Main road speed limits will remain faster. However, residential streets, shopping streets and streets close to public transport will be slower, to create a more economically vibrant and safer city. That’s because children, older people and people living with disabilities feel safer when going to local schools, shops, services and parks.

Myth #5: 30km/h limits are about revenue-raising

Speed limits are a low-cost tool in the governments’ toolbox against road deaths. Of course, not everyone obeys speed limits – two-thirds of Australians admit to speeding. Speed enforcement and street design changes may be needed in some cases to reduce driver speed and improve conditions for all street users.

Read more: Cycling and walking can help drive Australia's recovery – but not with less than 2% of transport budgets

Enforcement works and ensures credibility, because no single solution will work alone. For best results, state and territory governments will combine multiple tools to reduce speed, such as speed limits, public education, driver training, speed enforcement and street design.

A Safe Active Street in Perth, Western Australia, combines multiple design features to reduce traffic speed and increase its amenity. Author provided

A Safe Active Street in Perth, Western Australia, combines multiple design features to reduce traffic speed and increase its amenity. Author provided

Learn more

Not convinced? More myths to bust? Check out the Australian campaign 30please.org and the global United Nations Road Safety Week campaign #Love30 happening this week.

Introducing 30km/h limits is one of a suite of measures available to governments to bring about six compelling co-benefits to society: road safety, physical activity, air quality, liveability, equity and economic benefits.

All Australian states and territories should urgently introduce 30km/h speed limits to create streets that are safe, accessible and enjoyable for all.

Matthew Mclaughlin, PhD Candidate, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle; Ben Beck, Senior Research Fellow, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University; Julie Brown, Associate Professor, School of Medical Sciences, UNSW, and Program Head, Injury Division, George Institute for Global Health, and Megan Sharkey, Urban Studies Research Scholar, University of Westminster, and Adjunct Lecturer, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.