6 steps towards remaking the homelessness system so it works for young people

What would happen if we were able to redesign the homelessness services system so homelessness could be decreased and ultimately ended? Our newly released research report sets out an agenda of practical innovations. If implemented systemically, these changes could radically transform Australia’s response to youth homelessness within a decade.

What would happen if we were able to redesign the homelessness services system so homelessness could be decreased and ultimately ended? Our newly released research report sets out an agenda of practical innovations. If implemented systemically, these changes could radically transform Australia’s response to youth homelessness within a decade.

Every year, about 42,000 people aged 15-24, seeking assistance on their own, receive help from homelessness services. Between 2001 and 2006, this figure was about 32,000 per year.

The current specialist homelessness services system consists of some 1,500 agencies throughout Australia that support and house people seeking help due to homelessness. The system has increased in capacity from 202,500 clients and funding of A$383 million in 2008, to 290,300 clients and A$989.8 million in 2017-18.

When the Rudd government issued its 2008 white paper, The Road Home, the bold objective was to halve homelessness by 2020. It’s now all too clear the status quo of homelessness programs and services has failed to reduce homelessness. So what needs to change?

Rethinking the system

The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) has just released the research report, Redesign of a homelessness service system for young people, by a team of researchers from Swinburne University and the University of South Australia. It provides “a systems rethink” of the response to youth homelessness. The report will be presented to the first AHURI research webinar to be held next Wednesday, April 29, in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

The researchers began by asking questions about what could be done to stem the flow of young people into homelessness and to extricate young people from homelessness. This led to a reframing of the system in terms of a community-level ecosystem of services, programs and supports, organised locally. It’s a contrast to the status quo of centrally managed, targeted and siloed programs.

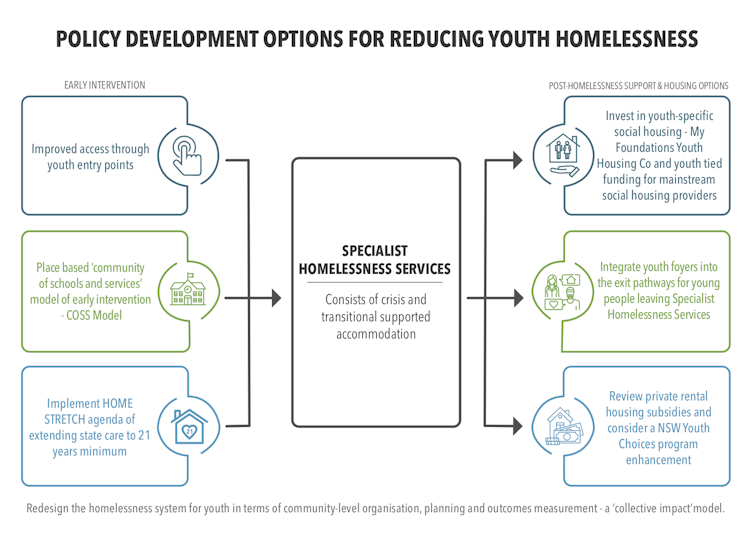

The diagram below shows what can be done to stem the flow into homelessness at the “front end” and what needs to be done at the “back end”.

3 key ways to ‘turn off the tap’

1. Effective early interventions are a priority. An innovative and now proven approach is the “community of services and schools” (COSS) model of early intervention. The Geelong Project, as well as newly established Albury and Mt Druitt sites in New South Wales, exemplify the COSS model.

This model reduced adolescent homelessness in the City of Greater Geelong by 40%. At the same time, it reduced disengagement from schooling and education for supported at-risk young people. The model has attracted international attention.

2. A second measure is extending state care and support for young people leaving the care and protection system at 18 years of age. This cohort is particularly vulnerable to becoming homeless.

A campaign has been under way to get the various states and territories to extend support until at least the age of 21. Victoria has begun a trial of this measure for 250 young people, but adequate support should be delivered to every care leaver in every Australian jurisdiction.

3. Creating entry points into the specialist homelessness services system for people seeking help is another Victorian reform. Anyone seeking assistance does not have to find their own way into the system – there is one point of contact in a community area where their needs can be assessed and appropriate support delivered. It’s a more efficient way of making use of limited resources.

No other state or territory has yet adopted the Victorian innovation.

3 ways to help create housing options

At the back end, there is a more costly set of options. Young people on their own are 16% of all specialist homelessness services clients and half of all single clients. But young people only manage to get 2-3% of social housing tenancies. A rethink of social housing is overdue.

1. In NSW, we have seen the founding of the first youth-specific social housing company in the world, My Foundations Youth Housing. In five years it has supported 885 tenants in some 300 properties with support from youth services partners. About 85% of the tenants are engaged in education, training and/or employment.

This approach could be and should be adopted across all Australian jurisdictions.

2. Many young people leaving homelessness services rely on Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Again in NSW, the Rent Choice Youth program provides a range of supplementary supports to complement rent assistance. Feedback from workers on the ground identifies this program as an effective innovation that merits being scaled up.

3. A third back-end measure is further development of the youth foyer model in Australia. Foyers provide supported accommodation on the basis of residents’ commitment to education, training and/or employment. In the past decade, some 15 foyers have been developed across Australia.

Apart from the high costs of building and operating foyers, the main issue is that if foyers are specifically part of the homelessness response, then new tenants should be exclusively selected from young people leaving specialist homelessness services programs. This is not necessarily standard practice.

There is a saying “same old thinking – same old results”, which will be a truism without system reform. As terrible as the current COVID-19 crisis is, it provides impetus and an opportunity for a major rethink of how we respond to youth homelessness.

The first AHURI Research Webinar Series event will be hosted on Wednesday, April 29 2020, from 10am to 11.30am. The free webinar will present findings from the research project, Redesign of a homelessness service system for young people. More details are available here.![]()

David MacKenzie, Associate Professor, School of Psychology, Social Work & Social Policy, University of South Australia and Tammy Hand, Research Fellow, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles