Tianjin Garden at the northern end of Spring Street is a symbol of Melbourne’s 40-year friendship with its sister city, Tianjin. Leonid Andronov/Shutterstock

Tianjin Garden at the northern end of Spring Street is a symbol of Melbourne’s 40-year friendship with its sister city, Tianjin. Leonid Andronov/Shutterstock

Sister cities aim to cultivate mutual understanding, international goodwill and peace. So how are Australian-Chinese sister cities faring as national-level tensions rise?

Read more: Yang Hengjun case a pivotal moment in increasingly tense Australia-China relationship

In new research, we found Australian councils and community and business representatives were generally satisfied with the educational and social benefits of having Chinese sister cities. However, most were less convinced about how effective these relationships had been in developing Chinese markets for Australian businesses or in attracting Chinese investment and tourists.

Melbourne and Tianjin announced the first Australian-Chinese sister-city relationship in 1980. Australian cities and towns now have over 500 sister-city relationships globally. Over 100 of these are with Chinese cities.

We surveyed 26 councils and conducted in-depth case studies of five – Darwin, Hobart, Melbourne, Warrnambool and Greater Geraldton. We looked at what’s working well and what needs rethinking.

Read more: Darwin port's sale is a blueprint for China's future economic expansion

Helping people connect

Most council, community and business representatives involved in these programs felt they did build goodwill and friendship between cities. This was based on traditional educational and social aspects of sister-city relationships such as school exchanges, cultural exchanges and increased intercultural understanding.

Significantly, a majority of council representatives did not believe national-level political tensions between China and Australia were barriers to developing these relationships. They agreed on the need to improve on current economic and business outcomes of their sister-city relationships.

Some sister cities have managed to support the development of export markets in China for local Australian businesses, especially small and medium-sized ones.

Although Australian councils face challenges in attracting Chinese investment to their communities, some are successful in stimulating knowledge-based exchange. For example, the City of Melbourne in partnership with RMIT University and Tianjin developed a leadership training program that has produced over 400 graduates operating across China. It has helped develop human capital networks and business opportunities for both Australians and Chinese.

Read more: Stephen FitzGerald: Managing Australian foreign policy in a Chinese world

Although social, educational and cultural benefits have been the traditional focus of sister cities, economic outcomes have received increasing attention in Australia. This is because many councils face pressure to create business opportunities and employment in their communities and to use rates income effectively.

Economic criteria might not have been the focus when councils selected sister cities in the past, which adds to the challenges of generating economic activity.

What are the barriers?

Some 85% of the councils cited business and trade as a key motivation and expectation for building sister-city relationships with China. Yet fewer than half believe the relationship has helped to develop Chinese markets for Australian businesses or to attract Chinese investment and tourists.

Understaffing and underfinancing are two important barriers to developing effective sister-city relationships.

Only 14% of the councils managed to dedicate one or two full-time staff members to manage these relationships. Only 21% had an annual budget of over $20,000 for sister-city management. Some did not even have a dedicated budget.

Only five councils had sister city relationship managers with Chinese language skills.

The lack of resources limited councils’ ability to explore and develop economic opportunities.

Sydney and Guangzhou celebrated their 30th anniversary as sister cities in 2016, but a lack of resources limits what many other councils get out of these relationships. City of Sydney

Sydney and Guangzhou celebrated their 30th anniversary as sister cities in 2016, but a lack of resources limits what many other councils get out of these relationships. City of Sydney

What are the keys to success?

Councils that generated economic benefits selected the right sister cities and built the relationships based on their strengths and needs, such as community well-being, tourism, waste management, smart city planning or knowledge-based economies.

These councils had clear strategic objectives. They knew what they wished to achieve from sister-city relationships for their communities. They understood their sister city’s motivations and interests. And they identified the complementary features of themselves and their sister city.

Successful councils understand the benefits and limitations of sister-city relationships. They have developed diversified partnerships with cities around the world.

Read more: Why mayors are looking for ideas outside the city limits

The ‘Give It Your Best Shot’ competition in 2016 involved nine councils promoting their relationships with Chinese sister cities. Mildura Rural City Council

The ‘Give It Your Best Shot’ competition in 2016 involved nine councils promoting their relationships with Chinese sister cities. Mildura Rural City Council

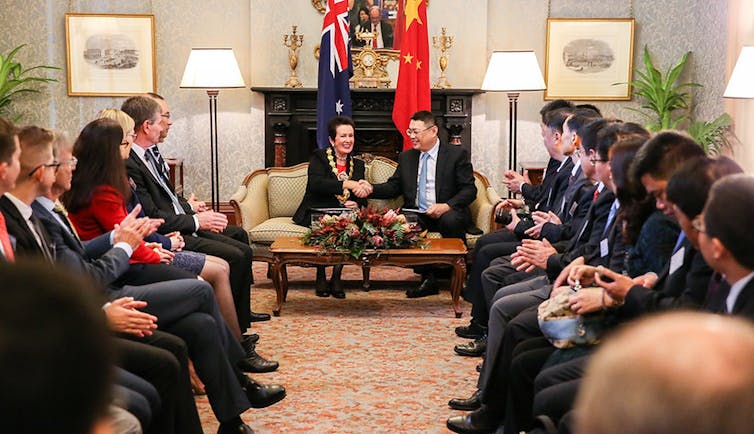

Successful councils also had communication strategies to promote their sister-city relationships to their own communities and those of their sister cities in China. They did so using videos, documentaries or newspapers. Examples include: the City of Hobart’s videos introducing its sister cities of Fuzhou and Xi’an to the local community; videos of the City of Darwin and the City of Melbourne showcasing the lord mayors’ visits to Chinese cities with a focus on regional cooperation and engagement for economic development; a video of the City of Warrnambool promoting the relationship to a Chinese audience; and the City of Greater Geraldton’s bilingual website China Connect fostering business and investment opportunities in both countries.

These communication strategies not only raised profiles of sister cities but also demonstrated to ratepayers the benefits of investing in city relationships.

Friends, but perhaps not for life

A long-term commitment can be a constraint if it lacks a strong business foundation. Currently, an effective mechanism to terminate inactive sister cities without damaging the sensitivities of both parties is absent.

In response, many councils have developed project-based fixed-term relationships. These allow for evaluation by each party for renewal at the end of the term, usually three to five years. Termed “friendship cities” or “international partners”, these arrangements allow a partnership to develop around a clearly defined project.

This new type of partnership will complement sister-city relationships and may flourish as cities in Australia and China seek to capitalise on economic benefits.

In our research, we found nothing but goodwill and the desire to build strong, fruitful and meaningful relationships between Chinese and Australians. If sister-city relationships are prudently and strategically managed for long-term mutual economic and social benefits, then the investment in money, time and effort on behalf of local communities is well worth it.

Shea X. Fan, Senior Lecturer in International Business, School of Management, RMIT University; Charlie Huang, Senior Lecturer, School of Management, RMIT University; Matthew Walker, Lecturer, School of Management, RMIT University, and Timothy Bartram, Professor of Management, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: The Comversation