Budget’s energy bill relief and home retrofit funding is a good start, but dwarfed by the scale of the task

The quality and performance of our housing have big impacts on the environment, cost of living and our health and wellbeing. The 2023-24 federal budget’s announcement of $1.6 billion for energy-saving upgrades to housing recognises the broad importance of retrofitting Australian homes.

Trivess Moore, RMIT University and Ralph Horne, RMIT University

The quality and performance of our housing have big impacts on the environment, cost of living and our health and wellbeing. The 2023-24 federal budget’s announcement of $1.6 billion for energy-saving upgrades to housing recognises the broad importance of retrofitting Australian homes.

Until now, much of the focus in Australia has been on improving the quality and performance of new housing. Recent changes to the National Construction Code improve minimum standards for new housing for the first time in more than a decade.

But more than 10.8 million existing dwellings fall short of the quality and performance needed for a low-carbon and affordable future. We must urgently shift our attention to delivering a deep retrofit – including solar panels, double glazing and other insulation – of the homes 99% of us live in. This would not only be good for the environment and reduce living costs, it would also improve our health and wellbeing and help increase the reliability of the energy grid.

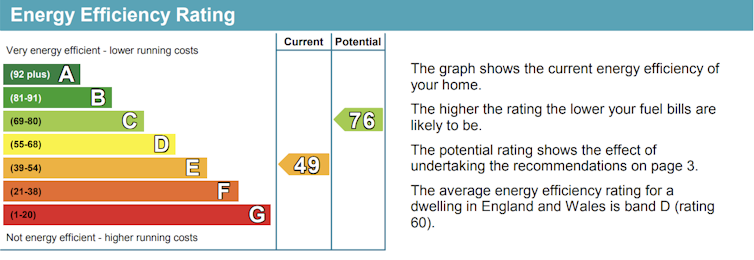

Most of our existing houses were built before minimum performance standards were adopted. Houses built before 1990 typically perform at a level of 1-3 stars on the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) (0 being worst, 10 best), compared to the 7 stars required of homes built after this October in most states.

Improving a house from 1 to 5 stars would reduce the energy needed for heating and cooling by about 70% in the Melbourne climate zone. And that means the household’s energy bills and emissions would be much lower too.

All this means the budget announcements are a welcome, but long-overdue, move to start a retrofit revolution in Australia.

What was announced?

The 2023-24 budget includes:

-

$3 billion in rebates that directly reduce energy bills for over 5 million households

-

$1.3 billion to set up the Household Energy Upgrades Fund, which will provide $1 billion to the Clean Energy Finance Corporation to finance home energy upgrades for around 110,000 households

-

$300 million to co-fund 60,000 social housing retrofits with the states and territories

-

$36.7 million to expand and upgrade NatHERS to apply to existing homes, which will give households better information for decisions on energy upgrades and renting or buying homes

-

expand and modernise the Greenhouse Energy Minimum Standards (GEMS) to cover more products.

This funding will help make our existing housing more energy-efficient and cheaper to run.

It’s a start but much more is needed

Much of the budget is focused on providing short-term relief for vulnerable households facing rising energy bills. But the bigger, long-term challenge is to help existing housing become more sustainable, affordable and liveable.

The cash rebate on energy bills is a short-term fix. The money could be better spent on prevention rather than cure. Retrofitting goes to the heart of the problem – ageing, energy-guzzling homes – and is a responsible use of taxpayer money.

The benefits of retrofitting a house outlive the current residents. It should be seen as an investment in the national housing stock rather than a handout to individual households. A cash rebate to reduce energy bills does nothing to improve housing performance.

The expansion of NatHERS to better account for existing housing is a welcome incentive to upgrade these homes. We need to make sure, though, that the information provided is robust, reliable and accessible to all households. Households need practical information about the cost-efficient retrofit actions they can take.

In other parts of the world, such as the United Kingdom and Europe, information about a home’s performance must be disclosed at point of sale or lease. This helps households make informed decisions. It also provides better data to governments about the quality and performance of the housing stock.

In Australia we have very poor data about our existing housing. We are developing policy and support with one hand tied behind our back.

The scale of the retrofit challenge is huge

Another key issue is the scale and urgency of the retrofit task we face. The budget announcement will make only a small dent in the work to be done. If we assume the performance of most of our existing homes is below-par, that means we will need to deliver deep retrofit to more than 45 homes every hour between now and 2050.

Upgrading 110,000 private homes and 60,000 social housing units is better than nothing, but we clearly need to scale up this work well beyond these numbers. This will require much more ambition and coordination from all levels of government.

We must also focus more on those who are most vulnerable, such as private renters on low incomes. Low-cost loans are good – if you qualify and have the means to repay them. What will those on the lowest incomes or without access to resources do?

We also need to make sure these loans don’t simply fund technology upgrades when there are cheaper and simpler things to do first, such as sealing gaps and cracks.

Scaling up is more than just a matter of providing support to households. We need to strengthen and develop retrofit capacity across the building industry to ensure demand can be met.

The industry needs certainty about the commitment of all levels of government to assist and sustain a low-carbon retrofit industry over time. This will allow the industry to plan and invest in capacity. This approach would help bolster the struggling construction industry while feeding into Australia’s wider net-zero ambitions.![]()

Trivess Moore, Senior Lecturer, School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University and Ralph Horne, Associate Deputy Vice Chancellor, Research & Innovation, College of Design & Social Context, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.