Matt Reynolds, architect and senior associate at Woods Bagot’s Sydney studio, weighs in on the stadium typology and why stadiums need to be designed to be better neighbours.

White Elephants, Unicorns and why we need hyper-flexible, infinitely purposed major venues.

The stadium is perhaps the most likely type of civic infrastructure to attract public scrutiny. Home to a vast range of experiences, the typology hosts the highs of public life – providing the stage for performances and grounds for sporting matches. Events are formative in every city’s public psyche, so their setting – the stadium – must meet the highest of standards.

But what happens when the event is over? Across the world, stadiums are only utilised for events approximately 10 to 20 percent of the year and left to languish the other 80 to 90 percent. Expensive and deeply antisocial, these buildings are a lost opportunity for social and financial contribution to their communities, owners, and operators. Stadiums should, and can, be useful every day of the week.

Knowing this, how can we design stadiums to be better neighbours? With the space and capacity to contribute to the wellbeing of nearby residents, foster community and ease the burden on support and crisis services – all without sacrificing the primary purpose of hosting events – the stadium contains a unique solution for a host of complex issues.

Bad neighbours: The problem with White Elephants.

Unavoidably for a typology as ancient as the Olympic Games themselves (77C BC), the stadium has encountered its fair share of critiques. Today, the least desirable outcome for a stadium’s designers, investors and community (short of being abandoned) is that the building will become a ‘White Elephant’.

Though whimsically titled, a White Elephant is a big problem. A barrier to their community and surrounding neighbourhood, White Elephants are a burdensome asset – underutilised, expensive to maintain, and even more expensive to remove, they fail to generate sufficient revenue to justify its cost.

Unfortunately, White Elephants can be found everywhere – it is near impossible to name a stadium that is in use 100 percent of the year and contributes to a sense of community within its local suburb. This widespread failure illuminates the missed opportunity for stadiums and other major venues to be good neighbours, tap into their potential and, in turn, reap the rewards.

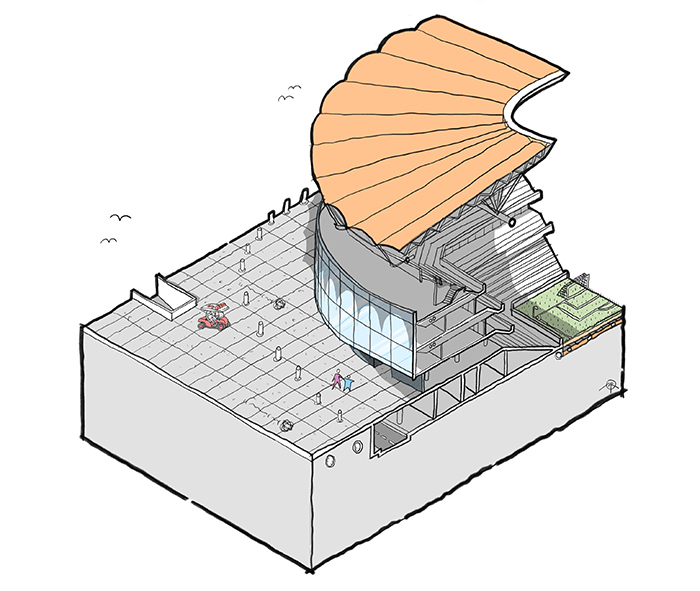

A White Elephant stadium on non-game day (illustration by Matt Reynolds)

Good neighbours: Enter the Unicorn.

In contrast to the White Elephant, a ‘Unicorn’ is both rare and highly desired. A non-existent and mythical creature, the moniker has been adopted by the tech startup world to describe something unique, profitable, exciting, and functional – Google, Facebook and Uber would qualify as Silicon Valley Unicorns. If we applied this logic to stadiums, a Unicorn would be profitable, sustainable, beautiful, functional and a good neighbour – one that contributes to its community through its consistent use.

Use-LESS Vs Use-FULL.

Unicorn stadiums don’t just appear; they take forethought and planning. Stadium owners, typically state governments, will often use major events (such as the Olympics or a World Cup) as a catalyst to kick off equally major surrounding infrastructure works. These decisions are based on the idea that such occasions create a post-event legacy, benefitting the city and validating the expenditure on both the stadium and the supporting infrastructure.

While related investment in public transport infrastructure is justified in a growing city, the stadium element of this equation unfortunately becomes a post-event burden. On these occasions, the venue fails due to a myopic focus on delivering for a primary event at the expense of local connection and services.

Consider this: In event mode, a stadium benefits its local community with increased spend in and around the venue by both locals and visitors. It also activates the surrounding neighbourhoods as spectators make their way to the venue. However, if we also design stadiums for non-event mode, we can offer a myriad of alternative, revenue-raising, community-improving uses such as childcare, libraries, night markets, adult education spaces, exhibition facilities, mental health, and community support services and more.

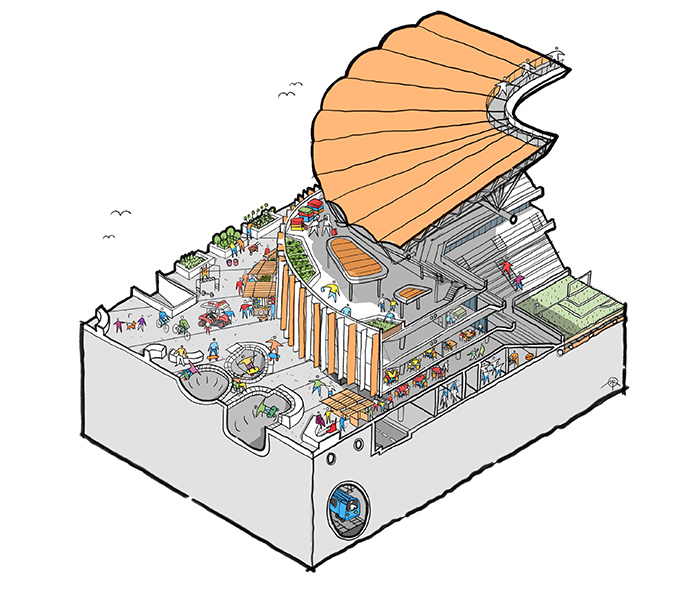

A Unicorn stadium on non-game day (illustration by Matt Reynolds)

The 365-day stadium: Active edges.

Physically and socially, a stadium shouldn’t be a barrier to community. Interestingly, almost every stadium is.

From Sydney to Tokyo, London to Hong Kong, examples of monolithic stadiums are easy to find. In a move that reduces maintenance costs but comes at a high price for the community, these stadiums are united by features such as sealed perimeters, impervious concrete and steel facades. Designed to keep people out, these venues reduce public architecture to security patrolled precincts with nothing to offer the passer-by.

The solution to such impermeability is an active edge. When stadiums are designed to invite people in, spectators and the local community become engaged participants. This reframing breathes life into a stadium on non-event days by offering reinterpretations and twists on the stadium’s offering – allowing it to function well in both modes.

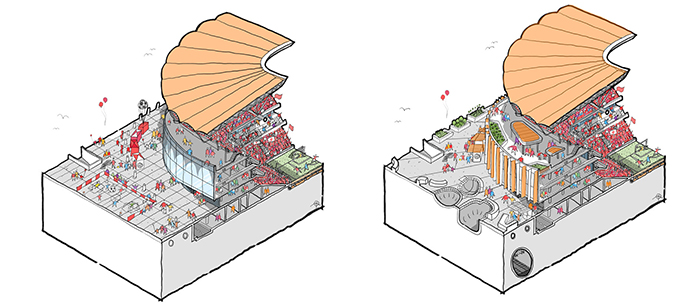

On event days, a stadium with an active edge will have restaurants and bars configured to face the field or stage, merchandise and retail outlets will engage with the internal concourse, and fan engagement – meeting players or testing skills – will be hosted on the plazas surrounding the stadium. On these days, the stadium is generally inward facing, presenting a closed, secure perimeter to the surrounding external plazas.

On non-event days, a stadium with an active edge will become more porous. Experiencing the concourse in the same way they experience the plaza, visitors can move in and out freely to access restaurants, bars, merchandise, retail outlets serving patrons in both directions, as well as the supporting amenities. This fluid mode can also host activities both around the plazas and the internal concourse, like pop-up food trucks, fresh food markets, hawker stalls, exhibitions, fitness circuits, education and more. Venue tours can still be in operation, but in a much more open and engaging atmosphere.

The best investment.

It’s important to note that fulfilling such vast social potential requires additional financial outlays in terms of initial capital, planning, and ongoing operation, but that the long-term social and financial benefits far outweigh such costs.

Undoubtedly, the most expensive stadium is the one found useless after its primary event is over. Notable examples of such devastating ends are the abandoned major venues of the 2016 Rio and 2004 Athens Olympics. Costing an estimated $4.56 billion and $2.94 billion respectively, Olympic infrastructure in Rio and Athens is a cautionary tale regarding the traps of inflexible, mono-purpose design.

The extra cost of integrating community usability into a stadium’s program would see its cost exceed that of an event-only venue, but early integration of these uses would be more beneficial to all. Long term, integrated stadiums are less of a burden to both owners and operators because – thanks to community use – they can overcome initial upfront capital costs with long term benefits to the local community.

White Elephant (left) Vs Unicorn (right) on game day (illustration by Matt Reynolds)

Small-scale changes, big-scale impact.

Major venues can be overwhelming in scale, but it is working at the smaller scale where we will find the solutions to hiding these buildings in plain sight – by integrating them into their local communities and the neighbourhoods they coinhabit.

365 days a year, event day or not, the stadium is part of the community – it’s time we designed them with this in mind.

Main image: A Unicorn stadium on non-game day – with an active edge (Illustration by Matt Reynolds).