Many places overseas require developers to build a certain proportion of affordable housing, but Victoria has opted for a voluntary negotiated approach. Lichtwolke/Shutterstock

Many places overseas require developers to build a certain proportion of affordable housing, but Victoria has opted for a voluntary negotiated approach. Lichtwolke/Shutterstock

Katrina Raynor, University of Melbourne; Georgia Warren-Myers, and Matthew Palm, University of Toronto

Housing in Australia is broken. Across the country, only 2% of private rentals are affordable for a person on the minimum wage. Less than 1% are affordable for a single person on the pension. There are 650,000 households who can’t afford housing at market rates in Australia right now and this figure is projected to reach over a million by 2036.

The abject failure to meet the housing needs of lower-income households is partially due to decades of underfunded social housing by government. Since the 1960s, the proportion of public housing in Australia has almost halved from 8% to 4.6% of total housing stock.

Scott Morrison’s newly re-elected government made no election statements relevant to social housing. That suggests this situation is unlikely to change soon.

Read more: Australia needs to reboot affordable housing funding, not scrap it

Leaving it to the private sector

As governments have stepped away from directly delivering affordable housing, more emphasis has been placed on the private sector and market forces to deliver this social good. Internationally, policies like inclusionary zoning require developers to provide a portion of affordable housing in return for planning permission.

For example, in San Francisco inclusionary zoning has been in place since 1992. This policy has generated 4,600 permanently affordable units since 2002. Developers received no incentives in return for being required to deliver this housing.

In Vancouver, developers wishing to build above a 3:1 plot ratio (for example, three storeys on 100% of the site, or six storeys on 50% of the site) in the CBD must provide social housing or other community amenities.

Read more: Ten lessons from cities that have risen to the affordable housing challenge

In contrast, the state of Victoria has very few regulations that encourage or enforce affordable housing or other community benefits in return for development permissions. The rezoning of Fisherman’s Bend for development is one particularly egregious example in Melbourne.

Victoria’s plan for negotiations

In 2018, the Victorian government took some initial steps towards involving private developers in providing affordable housing. It changed the Planning and Environment Act 1987 to designate affordable housing as a valid planning objective and created a mechanism for negotiated affordable housing agreements.

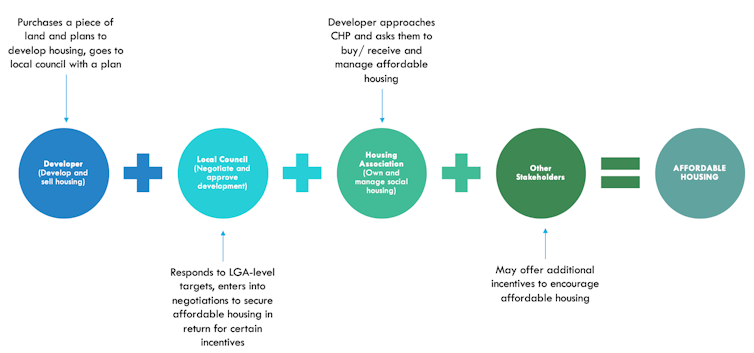

Local councils can now ask for affordable housing as part of planning approval processes. While these negotiations will inevitably generate a wide range of outcomes through a variety of arrangements, one likely permutation is shown below.

The local council and developer will enter into a negotiation and decide on a “reasonable” affordable housing contribution. In this instance, the developer will sell, “gift” or lease a number of units to a not-for-profit housing provider, which will manage the units and ensure eligible, low-income households occupy the home.

A negotiated path to delivering affordable housing. Author provided

A negotiated path to delivering affordable housing. Author provided

The difference between many international examples and Victoria is that these negotiations are voluntary. The argument is that voluntary negotiations avoid a one-size-fits-all solution and allows for flexibility and creativity in negotiations.

On the other hand, international research suggests voluntary programs often generate uncertainty and inequitable outcomes. They tend to generate less affordable housing than mandated systems. And they do so in more opaque ways.

Think about it: why would a developer voluntarily give up potential profit by selling or renting a property at a below-market rate? Such contributions would need to be enforced and/or incentivised.

Read more: Build social and affordable housing to get us off the boom-and-bust roller coaster

What can negotiation theory tell us?

Negotiation research can help us to understand the likely outcomes of these arrangements. It offers insights into stakeholder interests, the potential for mutual gains, and access to knowledge.

Stakeholder interests

Interests are the underlying values and priorities that motivate stakeholders’ demands or positions in negotiations. Interests in this context relate to the degree to which state government, local councils, or developers feel it is their responsibility to provide affordable housing. It relates to views on “valid” profit margins for developers and concerns about reputation.

It also relates to the priorities and strategies of the community housing providers, who are most likely to own and manage the housing delivered through these negotiations.

We know most developers don’t feel it is their responsibility to deliver affordable housing. Similarly, while some councils have explicit statements on affordability, this is not the case across Victoria.

The City of Port Phillip is unusual in having an explicit position on the council’s role in providing affordable housing. City of Port Phillip

The City of Port Phillip is unusual in having an explicit position on the council’s role in providing affordable housing. City of Port Phillip

Mutual gains

In places like San Francisco where affordable housing is required in all developments over a certain size, these requirements are built into feasibility calculations from the outset. Therefore, no incentives are included.

This also creates an even playing field for all developers in the consideration of land and development. As there is no negotiation or incentive that could shift the profit margin, the required approach places everyone on the same starting line. Further, the cost considerations are the same for all, when considering the purchase of a site and undertaking an analysis of the feasibility of a proposed project.

Voluntary negotiations only work when the parties at the negotiating table are interdependent – they must have something to gain and something to contribute in the negotiation or they wouldn’t be there. In places where negotiations are voluntary, incentives are often “bundled together” as sweeteners to offer to developers in the negotiation process. Possible incentives include car park waivers, increases in permissible developable area (i.e height or density bonuses) and fee reductions or waivers.

In Victoria, key incentives like allowing an increase in the floor area of a development – so-called floor area uplift – are difficult to implement in most local government areas. And expedited planning approvals are politically contentious and have limited impact on developers.

Inconsistency between councils may also allow developers to “shop around”. They are likely to avoid local government areas with a reputation for pursuing contributions.

As negotiations take place across Victoria the capacity for mutual gains for local communities and developers will be a key component in deciding how much affordable housing is provided and at what cost.

Access to knowledge

In negotiations, money and knowledge is power. Stakeholders are likely to hide or manipulate information in negotiations to support their own arguments and interests. This is particularly likely when there is little established trust between parties. Not only does this lead to undemocratic decisions made in a “black box”, it also creates opportunity for exploitation.

Negotiations will centre on trade-offs to achieve economically feasible developments that also include affordable housing. To engage in such discussions, a high degree of knowledge about development economics is required to allow for informed debate. While this is the bread and butter for developers, local councils are often far less resourced to engage in these discussions. There is work to be done in building the capacity of local councils in this area.

Acknowledging this, the authors of this article have built a calculator to help communicate many of the basic premises behind development economics and affordable housing trade-offs.

Have your say on affordable housing

We don’t know yet enough about interests, mutual gains or access to knowledge to fully understand the landscape of this change to Victorian housing policy. And that is why we are surveying the affordable housing industry to gather this feedback.

If you are a private developer, local or state government representative with involvement in residential development or affordable housing policy, a not-for-profit housing provider, or consultant to the housing industry, then we want to hear from you.

Please click here to take the survey.

Katrina Raynor, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Transforming Housing Project, University of Melbourne; Georgia Warren-Myers, Senior Lecturer in Property, and Matthew Palm, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Magic Bricks