The Australian Football League’s announcement of a Tasmanian football club – likely to be called the Tassie Devils – is now a formality, after the federal goverment’s pledge of A$240 million to a new stadium and precinct in Hobart.

A new stadium is the last of 11 AFL requirements for a Tasmanian club to become the league’s 19th team, joining ten Victorian clubs and two each from the other four states.

The view was that UTAS stadium in Launceston could be upgraded but that upgrading Hobart’s Bellerive Oval (known as Blundstone Arena) made less sense than a new facility in Hobart’s CBD, on Macquarie Point, north of Hobart’s Constitution Dock.

The Tasmanian government wants the stadium, which it will own, to anchor a new “arts and sports” precinct. It will contribute $375 million of the estimated cost of $715 million. Another $85 million will come from loans against future land sales and leases in the revitalised area. The AFL will contribute the final $15 million. There will also be $10 million to build a headquarters for the new club.

This is part of $360 million the AFL will spend on AFL in Tasmania over the next ten years, with $209 million to subsidise the new club and $120 million to support grassroots participation and the development of talented players.

Compared with the $3.4 billion the federal government has committed to buildings for the 2032 Brisbane Olympics, its contribution to the Hobart arena is relatively minor.

But critics say the stadiums in Hobart and Launceston are adequate, and that the money would be better spent on public housing – with rents having risen 45% in the past five years. As novelist Richard Flanagan put it:

Tasmania doesn’t have a stadium problem. It has a housing and homelessness problem.

The problem with this argument is that economies are dynamic, not static. Was it also wrong to have built the Sydney Opera House because of housing issues in the late 1960s?

Without an AFL team and new stadium, Tasmania is likely to still have a homeless problem. In fact, the problem may even be worse without economic activity the new team and stadium will bring.

Economic rationale

The rationale for the federal and state governments is that a new stadium is a precondition for a Tasmanian AFL, and that both together will generate $2.2 billion in economic activity over 25 years according to Tasmanian government.

Governments favour infrastructure projects because construction has a high “multiplier effect” – generating flow-on benefits. The Tasmanian government estimates construction will generate $300 million in economic activity and 4,200 jobs. It expects the stadium when operational to sustain 950 jobs and generate $85 million in economic activity a year.

This will depend on hosting major events along with AFL fixtures. The Tasmanian government’s business case anticipates the venue hosting at least 44 events a year, attracting 123,500 overseas and interstate visitors.

These expectations will be buoyed by the success of the AFL’s “Gather Round” in mid-April, in which all AFL games were played in South Australia. A reported $15 million state government contribution generated an estimated $85 million in economic benefit from 60,000 interstate fans.

The case for a Tassie team

In assessing this decision, we can’t just consider the business case for the stadium. It’s about the case for a Tasmanian AFL club.

Tasmania may only have a total population of 558,000 (with 247,000 in Hobart) but its claim to have an AFL team is as good as the Gold Coast (home of the Suns, population 640,000) or even Geelong (home of the Cats, population about 280,000). Townsville, where the North Queensland Cowboys play in the NRL, has 235,000 people.

According to James Coventry’s 2018 book Footballistics: How the Data Analytics Revolution is Uncovering Footy’s Hidden Truths, no other state has a higher percentage of AFL fans. In WA it’s 62.3%, in South Australia 75.7%. In Victoria, 70.2%. In Tasmania it’s 79%.

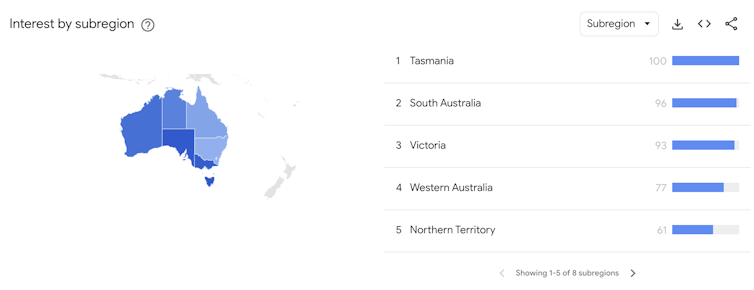

Google Trends result for ‘AFL’, 12 months to April 2023. CC BY

Google Trends result for ‘AFL’, 12 months to April 2023. CC BY

Aussie Rules is really the only game in town on the Apple Isle, writes Hunter Fujak his 2021 book Code Wars, which explores the nation’s “Barassi Line” split between AFL and National Rugby League. The percentage of Tasmanians that only follow the AFL is 35%, compared to the national average of 19%.

More than the bottom line

Yes, the AFL is a multimillion-dollar business, but it’s also a community organisation, managing a public good. As the Richmond president Peggy O’Neal put it in Coventry’s book:

It’s sort of a blend of strict financial business and not for profit […] If we wanted just to make money, our model would be quite different.

This explain the AFL’s preparedness to commit $345 million over the next decade to support the new club, as well as grassroots football across Tasmania, to ensure local community footy doesn’t lose out from the resources and energy being put into the AFL team. This will include building 70 new ovals across the state, and funding football academies in Hobart, Launceston and Penguin (west of Devonport on the north coast).

The AFL has subsidised the AFLW for similar reasons. It’s about more than just the bottom line.

Tasmania has waited far too long for a team of its own. The entry of the Tassie Devils into the AFL can be justified on economic, social and (most of all) footy grounds.

Tim Harcourt, Industry Professor and Chief Economist, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.