Trismegist san, Shutterstock

William Geary, The University of Melbourne; Dale Nimmo, Charles Sturt University; Julianna Santos, The University of Melbourne, and Kristina J Macdonald, Deakin University

Trismegist san, Shutterstock

William Geary, The University of Melbourne; Dale Nimmo, Charles Sturt University; Julianna Santos, The University of Melbourne, and Kristina J Macdonald, Deakin University

Landscapes that have escaped fire for decades or centuries tend to harbour vital structures for wildlife, such as tree hollows and large logs. But these “long unburnt” habitats can be eliminated by a single blaze.

The pattern of fire most commonly experienced within an ecosystem is known as the fire regime. This includes aspects such as fire frequency, season, intensity, size and shape.

Fire regimes are changing across the globe, stoked by climate and land-use change. Recent megafires in Australia, Brazil, Canada and United States epitomise the dire consequences of shifting fire regimes for humanity and biodiversity alike.

We wanted to find out how Australian fire regimes are changing and what this means for biodiversity.

In our new research, we analysed the past four decades of fires across southern Australia. We found fires are becoming more frequent in many of the areas most crucial for protecting threatened wildlife. Long unburnt habitat is disappearing faster than ever.

Uncovering long-term changes

“Fire regimes that cause declines in biodiversity” was recently listed as a key threatening process under Australia’s environmental protection legislation.

However, evidence of how fire regimes are shifting within both threatened species’ ranges and protected areas is scarce, particularly at the national scale and over long periods.

To address this gap, we compiled maps of bushfires and prescribed burns in southern Australia from 1980 to 2021.

We studied how fire activity has changed across 415 Australian conservation reserves and state forests (‘reserves’ hereafter), a total of 21.5 million hectares. We also studied fire activity within the ranges of 129 fire-threatened species, spanning birds, mammals, reptiles, frogs and invertebrates.

We focused on New South Wales, the Australia Capital Territory, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia because these states and territories have the most complete fire records.

Large areas of long unburnt forest in New South Wales were burnt in the 2019-20 fire season. Tim Doherty

Large areas of long unburnt forest in New South Wales were burnt in the 2019-20 fire season. Tim Doherty

More fire putting wildlife at risk

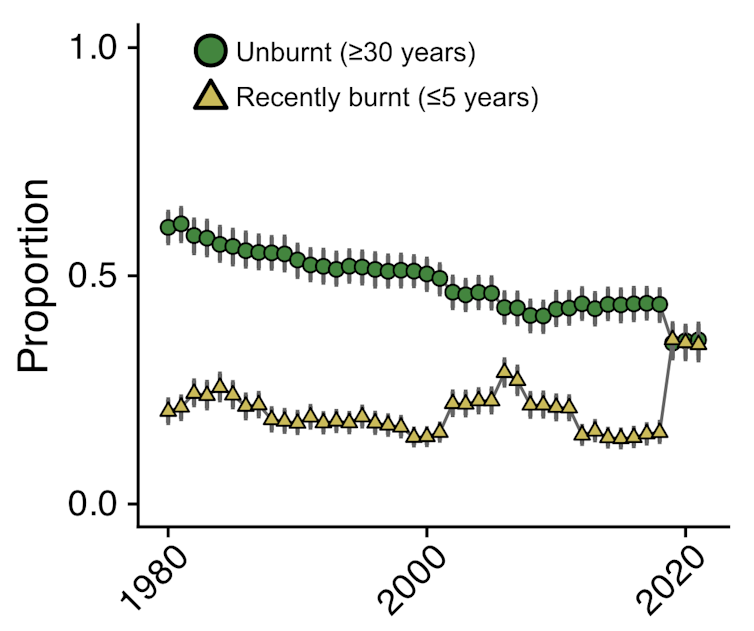

We found areas of long unburnt vegetation (30 years or more without fire) are shrinking. Meanwhile, areas of recently burnt vegetation (5 years or less since the most recent fire) are growing. And fires are burning more frequently.

On average, the percentage of long unburnt vegetation within reserves declined from 61% to 36% over the four decades we studied. We estimate the total area of long unburnt vegetation decreased by about 52,000 square kilometres, from about 132,000 sq km in 1980 to about 80,000 sq km in 2021. That’s an area almost as large as Tasmania.

At the same time, the mean amount of recently burnt vegetation increased from 20% to 35%. Going from about 42,000 sq km to about 64,000 sq km in total, which is an increase of 22,000 square kilometres.

And the average number of times a reserve burnt within 20 years increased by almost a third.

While the extent of unburnt vegetation has been declining since 1980, increases in fire frequency and the extent of recently burnt vegetation were mainly driven by the record-breaking 2019–20 fire season.

Changes in the proportions of unburnt and recently burnt vegetation across 415 conservation reserves and state forests in southern Australia. Tim Doherty

Changes in the proportions of unburnt and recently burnt vegetation across 415 conservation reserves and state forests in southern Australia. Tim Doherty

Which areas have seen the biggest changes?

The strongest increases in fire frequency and losses of long unburnt habitat occurred within reserves at high elevation with lots of dry vegetation. This pattern was most prominent in southeastern Australia, including the Kosciuszko and Alpine national parks.

In these locations, dry years with low rainfall can make abundant vegetation more flammable. These conditions contribute to high fire risk across very large areas, as observed in the 2019–20 fire season.

Threatened species living at high elevations, such as the spotted tree frog, the mountain skink and the mountain pygmy possum, have experienced some of the biggest losses of long unburnt habitat and largest increases in fire frequency.

Multiple fires in the same region can be particularly problematic for some fire-threatened animals as they prevent the recovery of important habitats like logs, hollows and deep leaf-litter beds. Frequent fire can even turn a tall forest into shrubland.

Fire-threatened species Australia include (clockwise from top-left) the kyloring (western ground parrot), mountain skink, stuttering frog and mountain pygmy possum. Clockwise from top-left: Jennene Riggs, Jules Farquhar, Jules Farquhar, Zoos Victoria.

Fire-threatened species Australia include (clockwise from top-left) the kyloring (western ground parrot), mountain skink, stuttering frog and mountain pygmy possum. Clockwise from top-left: Jennene Riggs, Jules Farquhar, Jules Farquhar, Zoos Victoria.

What does this mean for Australia’s wildlife?

Fire management must adapt to stabilise fire regimes across southern Australia and alleviate pressure on Australia’s wildlife.

Indigenous land management, including cultural burning, is one approach that holds promise in reducing the incidence of large fires while providing fire for those species that need it.

Strategic fire management within and around the ranges of fire-threatened species may also help prevent large bushfires burning extensive portions of species’ ranges within a single fire season.

We can also help wildlife become more resilient to shifting fire regimes by reducing other pressures such as invasive predators.

However, our efforts will be continually undermined if we persist in modifying our atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. This means conservation managers must also prepare for a future in which these trends continue, or hasten.

Our findings underscore the increased need for management strategies that conserve threatened species in an increasingly fiery future.

William Geary, Lecturer in Quantitative Ecology & Biodiversity Conservation, The University of Melbourne; Dale Nimmo, Professor in Ecology, Charles Sturt University; Julianna Santos, Research fellow in Ecology and Conservation Science, The University of Melbourne, and Kristina J Macdonald, PhD Candidate, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.