Australian households produce about 12 million tonnes of waste every year. That puts the sector almost on par with manufacturing or construction.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. With support, households can change patterns of consumption and develop a low-waste lifestyle. Our new research explores how Australians engage with low-waste living.

We interviewed residents about their existing waste management practices. We then invited them to design and implement their own six week household experiments. Their ideas ranged from home gardening and repairs to zero-plastic cooking and bulk store shopping. And then we brought them all together with policymakers to share their experiences.

The results show that householders were keen to experiment with change but that low-waste living is not easy.

Taking responsibility for recycling

For years, Australia sent waste materials offshore for recycling. When China banned these imports in 2018, Australian governments had to fast-track better waste management policies.

In a true circular economy, nothing is wasted. Resources are valued and continuously reused as they cycle through the system.

But in the transition phase, the focus has been on recycling as a way to reduce the amount of waste sent to landfill.

Kerbside recycling bins are often contaminated with general waste that cannot be recycled. The material piles up at waste management facilities before it can be sorted. JONO SEARLE/AAP

Kerbside recycling bins are often contaminated with general waste that cannot be recycled. The material piles up at waste management facilities before it can be sorted. JONO SEARLE/AAP

Soft plastics have been particularly problematic. In recent years, households have been encouraged to take soft plastics, mostly packaging, back to the supermarket. But the REDcycle soft plastics collection scheme was overloaded. Coles and Woolworths paused collection on November 9 2022 after it was revealed that the scheme had been unable to deliver on its recycling promises for months.

That followed the collapse of recycling company SKM in Victoria in 2019. Stockpiles of unprocessed rubbish filled warehouses, while other recycling was sent directly to landfill.

Several Australian states banned single-use plastics, most recently Victoria, but success will depend on making it easy to use alternatives.

Households produced the bulk of Australia’s plastic waste (47%) and food/organic waste (42%) in 2018-19. Improving these statistics requires changes in social norms around lifestyles and consumption practices in conjunction with changes in retail practices, supported by regulation and new collection infrastructure.

Previous research has shown that households operate on the level in between the micro-level of individuals and the macro-level of communities. But there is a lack of appreciation of the role households can play in the transition to sustainability.

Experimenting with change

Transitioning to low-waste living requires changes in household consumption and waste management practices.

The Covid lockdowns in Victoria provided both an opportunity and an incentive for many people to change their consumption practices. However, as life returns to the ‘new normal’, many find it far from easy to maintain a low-waste life.

We conducted a series of innovative household experiments with 19 Melbourne-based participants.

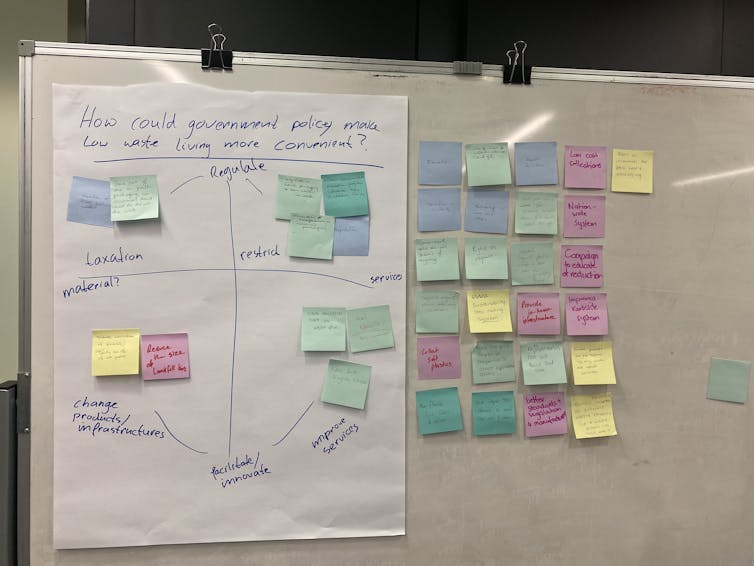

Workshop participants offered many suggestions in response to the question: How could government policy make low-waste living more convenient? Supplied, Author provided

Workshop participants offered many suggestions in response to the question: How could government policy make low-waste living more convenient? Supplied, Author provided

A mother of two students wanted to be 100% waste free for six weeks, while another mother focused on zero-plastic cooking. Others committed to trying out bulk stores, while a woman living by herself started a garden. Another single woman wanted to learn how to repair her clothes and her bike, while a part-time salesworker living with his husband wanted to create a 3-week low-waste action challenge for his friends.

What we learned

Participants said they found household change very challenging.

We were told the experiments required extra mental capacity, time, money and motivation. Householders also needed more information and support to achieve, then maintain, the desired change in practices.

For some, the experience provided an incentive to try something different, such as walking the extra distance to the bulk food store rather than taking the easy option of the supermarket.

Bulk food stores encourage customers to bring their own reusable containers from home, or use more environmentally-friendly packaging such as paper bags, eliminating soft plastic packaging. By Jack Frog at shutterstock.com

Bulk food stores encourage customers to bring their own reusable containers from home, or use more environmentally-friendly packaging such as paper bags, eliminating soft plastic packaging. By Jack Frog at shutterstock.com

Changes didn’t always stick. A transition to shampoo and conditioner bars required extensive research and was too hard for one: “Just that one switch was so intense … it was expensive as well.”

Supermarkets were a major source of frustration around unwanted plastics: “The packaging is such a big problem. It’s just ridiculous. It should be stopped … There are very few items that you can buy that doesn’t have some sort of packaging.”

Social relationships were important in low-waste living. One woman said her family told her they were not prepared to go any further on the zero waste journey, while another had her husband and kids supporting her all the way.

The challenge of reducing food waste with children in the house came up too: “It’s challenging to reduce how much food gets wasted with children. I have reduced how much I cook … I’ve tried to do stocktakes of my freezer, my pantry, the fridge … to really focus on meal planning … But it’s really, really challenging … I think if it was just me, I would have a lot more success.”

Facebook groups were a useful resource “because it does make you realise that there are other people who are trying to save every piece of plastic from going in the bin”.

Householders articulated many policy and system changes required to make low-waste living easier including legislation on high waste producers, banning polluting products, improving recycling infrastructure, creating markets for recycled products, encouraging innovation, providing better information and improving product labelling.

The householders were aware of low-waste alternatives in different parts of the world and frustrated by system failure in Australia.

“We need support and systemic change from the government (policy) and businesses (innovation) to drive down the amount of plastics associated with our everyday products,” one participant said.

The waste crisis became more acute in 2019 after China refused to continue accepting Australia’s contaminated waste for recycling, prompting protests. JAMES ROSS/AAP

The waste crisis became more acute in 2019 after China refused to continue accepting Australia’s contaminated waste for recycling, prompting protests. JAMES ROSS/AAP

Low-waste living should be made easy

Ultimately, our research shows substantial changes are needed to make low-waste living easy.

We found experimentation within the home could be useful in designing and testing new policy. The experience can connect policymakers to real people and the things that matter to them, such as parenting, friendships, sharing a meal, ‘making ends meet’, and caring for others.

If the transition to a circular economy is to be successful, it needs to be planned from the perspective of everyday life within households.

Acknowledgements: We are deeply grateful for all participants in the study for generously sharing their time, insights and efforts with us.

Rob Raven, Professor and Deputy Director (Research), Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University; David O. Reynolds, Postdoctoral Fellow, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore; Jo Lindsay, Professor of Sociology, Monash University, and Ruth Lane, Associate Professor in Human Geography, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.