Rolf_52/Shutterstock

Rolf_52/Shutterstock

Australia urgently needs housing types that meet the needs of older women facing homelessness. One such model is Chinese siheyuan courtyard housing, which provides safe, affordable and private living spaces while maintaining a sense of community. It has potential for adapting existing buildings for re-use in Australia in a way that makes financial, social and environmental sense.

Women over 45 are one of the fastest-growing groups of people who are homeless in Australia. In 2020, an estimated 405,000 women over 45 were at risk of housing affordability stress and hence becoming homeless. Considering the shortage of affordable housing, an ageing population and the lifelong economic disadvantage that women experience, this problem requires a speedy solution.

Read more: 400,000 women over 45 are at risk of homelessness in Australia

A simple (and obvious) solution for older women facing homelessness is to provide them with access to appropriate, safe and affordable homes for the long term. So why is this problem so difficult to solve?

Recent attempts to meet this need for older women’s housing include “pop-up” or “meanwhile use” accommodation in vacant aged-care facilities and tiny houses. While both types provide good short-term options, they do not create long-term housing that meets older women’s needs to age in place and have secure tenure and a sense of belonging. All these aspects are important for their well-being.

Read more: 'Meanwhile' building use: another way to manage properties left vacant by the COVID-19 crisis

What if we were to take the idea of adapting existing buildings and merge it with the idea of tiny homes? Chinese courtyard housing – siheyuan – has some important principles that could be culturally adapted to the Australian context.

Finding new spaces in old stock

Adaptive reuse involves the conversion of new spaces within old ones. An existing building is recycled by integrating a new set of functions into the existing skin to suit the needs of new inhabitants.

This is not a new concept – think of the Hagia Sofia in Istanbul, originally a mosque, then church, now museum. Or Paddington Reservoir in Sydney, originally infrastructure, then petrol station, then ruin, now urban performance space.

Adaptive reuse works on a triple-bottom-line approach: economic, environmental and socio-cultural. Recycling an existing building is cheaper, better for the environment and ensures the collective memory of a place is not erased. For buildings as for older women, respect for age, connection to place and care for the environment are important.

Read more: Unused buildings will make good housing in the world of COVID-19

Chinese wisdom in an Australian context

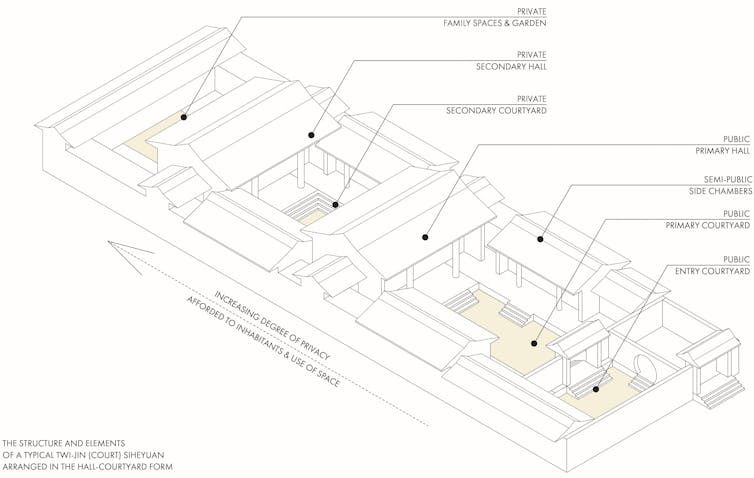

The name “siheyuan” translates into quadrangle courtyard housing. This type of housing comes from traditional Confucian ideas of the extended family unit, arranged around a courtyard or series of courtyards with graduated levels of privacy.

Hugo Chan, Author provided

Hugo Chan, Author provided

The interesting thing about the siheyuan arrangement is the highly ordered series of rooms with private units organised around open spaces and communal halls for gatherings. In Beijing today, an estimated 400,000 courtyard houses remain. About 500 have been preserved as historic sites.

The hierarchical order of the siheyuan presents a great opportunity for adapting it to suit the needs of older women. It’s a type of co-housing arrangement: people live independently but together, sharing some facilities like open space and areas to come together for occasional meals. This model could form part of the rise in shared housing configurations.

Read more: Co-housing works well for older people, once they get past the image problem

The courtyards meet the needs of older women to maintain a strong connection to a garden space, with potential for them to be active in maintaining this area. The courtyards promote social contact and exercise, as well as space for quiet contemplation. This interior-landscape connection is important to the well-being of older women.

The connections between private living areas, courtyards and gardens promote well-being through social contact and exercise. ByLorena/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

The connections between private living areas, courtyards and gardens promote well-being through social contact and exercise. ByLorena/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

The hall serves as a social connector. It’s a place for communal activities, connecting with family or friends, creative projects or listening. Women retain their sense of independence; they decide when they participate.

Another important requirement for older women is to have the space to welcome family and friends, so they maintain their social connections to the world. The hall is an efficient way to share space that everyone needs, but only some of the time.

The private units ensure the independence, safety and sense of belonging that older women need. Cultural and social needs are met easily within one’s personal domain.

The small luxury of having a room of one’s own should not be underestimated. Many older women have rarely had this luxury. For them, it provides much-needed dignity.

Read more: What do single, older women want? Their 'own little space' (and garden) to call home, for a start

The adaptation mindset

This sort of adaptive reuse is not just about what we do with existing buildings. It’s also about adapting cultural wisdom, and ideas from the past, to develop alternative ways of living together. Many currently underutilised or vacant buildings in Australia could be adapted to courtyard housing.

It will need a radical shift in policy and developer-driven economics. But this opportunity would meet so many current needs of older women, be good environmental practice and provide social housing. As Confucius said, “Everything has beauty, but not everyone sees it.”

The financial burden on taxpayers and service providers is dramatically reduced by providing secure affordable housing in the first place. The solution to the problem of homelessness lies not in our obsession with new housing models or new development, but perhaps, if we look hard enough, in our existing urban fabric. Right under our noses, existing buildings offer opportunities ripe for adaptation.

Read more: What sort of housing do older Australians want and where do they want to live?

Samantha Donnelly, Lecturer, School of Architecture, University of Technology Sydney and Hugo Chan, Sessional Academic, UNSW Built Environment, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.