More than ever, it’s time to upgrade the Sydney–Melbourne railway

Is a new, dedicated, high-speed rail link the answer? The Labor government thinks so: among the plans flagged last week when Governor-General David Hurley opened parliament was a pledge to begin work on “nation-building projects like high-speed rail”.It’s 14 years since former NSW rail chief Len Harper the rail link between Australia’s two largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne, as “inadequate for current and future needs”. And it’s 31 years since former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam put the problem more bluntly during a TV interview:

there are no cities in the world as close to each other with such large population as Sydney and Melbourne which are linked by so bad a railway.

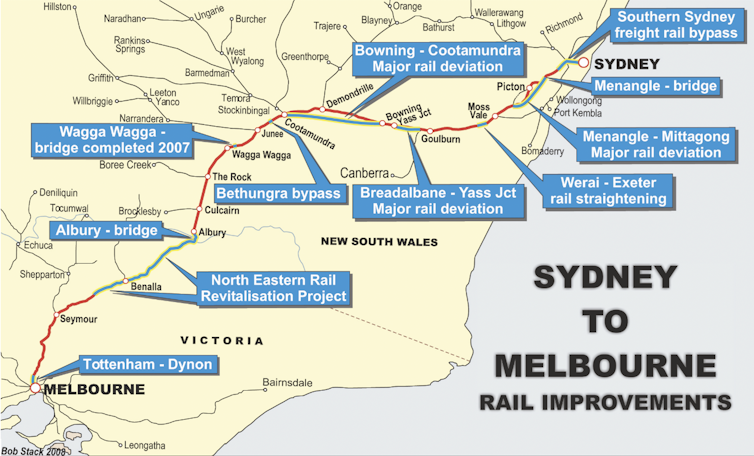

Despite remedial work by the Australian Rail Track Corporation since it leased the NSW section of track, the rail link’s most serious problem – its “steam age” alignment – remains.

Is a new, dedicated, high-speed rail link the answer? The Labor government thinks so: among the plans flagged last week when Governor-General David Hurley opened parliament was a pledge to begin work on “nation-building projects like high-speed rail”.

That vision isn’t new. A high-speed rail link between Sydney and Melbourne – with trains operating at speeds of 250 kilometres per hour or more on their own track – was first proposed in 1984 by CSIRO. Since then, it has been examined in depth no fewer than three times, most recently in a report released by the Gillard government in 2013.

After it lost government, Labor promoted the idea of a High Speed Rail Planning Authority. Infrastructure Australia added its voice in 2016 with a call for governments to start reserving land for a future high-speed rail link between Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane.

The Coalition government preferred a less ambitious option. Its National Faster Rail Agency part-funded numerous studies assessing the viability of lifting speeds on the existing route to between 160 and 250 km per hour.

That approach could prove to be the best way forward, at least in the short to medium term. A high-speed link between Sydney and Melbourne might still be built, but it could take 20 years or more to begin operating. In the meantime, faster freight and passenger services are needed between Australia’s two largest cities if we are to meet our commitment to reducing carbon emissions from transport.

On average, according to Rail Futures calculations, rail freight is three times more energy efficient than road, and significantly more energy efficient than cars or planes in moving people.

Limitations of the existing line

Why has rail been losing ground to roads? The mainline track between Sydney and Melbourne – about 640 km of it in New South Wales and 320 km in Victoria – has many defects, some of which became more widely known after the fatal derailment of an XPT in Victoria in February 2020.

Much of the track within New South Wales has a “steam age” alignment to ease grades, adding an extra 60 km to the journey. Far too many tight-radius curves slow down freight and passenger trains.

On the same TV program as Whitlam made that earlier remark, another former state rail chief, Ross Sayers, argued that a tilt train – a train designed to negotiate curves more quickly – could travel at more than 200 km per hour between Sydney and Melbourne on an upgraded alignment. “We could set the passenger transit time at five, or perhaps five and a half hours,” he said. This is still a good, viable option.

Five and a half hours would be half the time the current XPT services take. And the gain isn’t purely speculative: when Queensland straightened much of its track between Brisbane and Rockhampton for faster and heavier freight trains – and then, in 1998, introduced a new tilt train – passenger transit time halved from 14 to seven hours.

One major improvement to the Sydney–Melbourne line in recent decades was the installation in 2008 of centralised traffic control signalling, which allows for the remote control of points and signals along the track. Why the track between Australia’s two largest cities had to wait so long even for that upgrade, which was essential for efficient train operations, is a good question. New Zealand’s two largest cities, Auckland and Wellington, were linked by such signalling 42 years earlier, in 1966.

The impact on freight and passengers…

Fifty years ago, rail and road held roughly equal shares of the land freight moving between Sydney and Melbourne. Trucks took about 15 hours to traverse a two-lane Hume Highway that was poorly aligned in many places.

Mainly with funds from the federal government, the entire Hume Highway was subsequently rebuilt to modern engineering standards at a cost of about $20 billion in today’s terms. Much larger trucks can now move freight between Sydney and Melbourne in ten hours.

The pro-road policies don’t end there. Low road-access road pricing for trucks – an estimated hidden subsidy of more than $8 per tonne – has combined with the substandard nature of the Sydney–Melbourne rail track to reduce rail’s share of palletised and containerised freight to about 1%, according to rail freight operator Pacific National.

The consequences include an increased risk of fatalroad crashes, higher highway maintenance costs, pressure for more road upgrades, and increased emissions.

A detailed 2001 track audit how 197 kilometres of new track built to modern engineering standards – including three major deviations from the existing alignment – could bypass 257 km of substandard track. Freight train transit times would then be reduced by nearly two hours.

I estimate that if rail were to regain a 50% share of the freight between our two largest cities, emissions would fall by over 300,000 tonnes per annum. In Australia, this is the equivalent of taking about 100,000 cars off the road.

As for freight, so for passengers. By 2019, more than nine million passengers were flying each year between Sydney and Melbourne, making this the second-busiest air corridor in the world. Tilt trains on upgraded track would speed the passenger journey appreciably while providing long-overdue improvements to rail services between Sydney and regional New South Wales and from Melbourne and Sydney to Canberra.

… and on climate

Along with improving resilience of the track to the impacts of climate change, if Australia is serious about decarbonisation, the effort must extend to transport. A significant portion of road freight and passengers will need to shift to rail. As the International Energy Agency noted last year, “Rail transport is the most energy‐efficient and least carbon‐intensive way to move people and second only to shipping for carrying goods.”

The agency also stressed that “aviation growth will need to be constrained by comprehensive government policies that promote a shift towards rail” in order to achieve net-zero emissions.

If Australia fails to bring the Sydney–Melbourne track into the 21st century, we can expect not only excessive greenhouse gas emissions but also growing costs from many more trucks on the Hume Highway. Congestion at Melbourne and Sydney airports will worsen, and Australia will be left increasingly out of step with other countries in Europe, North America and Asia.![]()

Philip Laird, Honorary Principal Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles