Burdun Iliya/Shutterstock

Burdun Iliya/Shutterstock

The World Health Organisation has always been interested in housing as one of the big “causes of the causes”, of the social determinants, of health. The WHO launched evidence-based guidelines for healthy housing policies in 2019.

Australia is behind the eight ball on healthy housing. Other governments, including in the United States, United Kingdom and New Zealand, acknowledge housing as an important contributor to the burden of disease. These countries have major policy initiatives focused on this agenda.

In Australia, however, we do housing and we do health, but they sit in different portfolios of government and aren’t together in the (policy) room often enough. Housing should be embedded in our National Preventive Health Strategy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to rethink how we approach health and protect our populations. It has amplified social and economic vulnerability. The pandemic has almost certainly brought housing and health together in our minds.

Housing – its ability to provide shelter, its quality, location, warmth – has proven to be a key factor in the pandemic’s “syndemic” nature. That is, as well as shaping exposure to the virus itself, housing contributes to the social patterning of chronic diseases that increase COVID-19 risks.

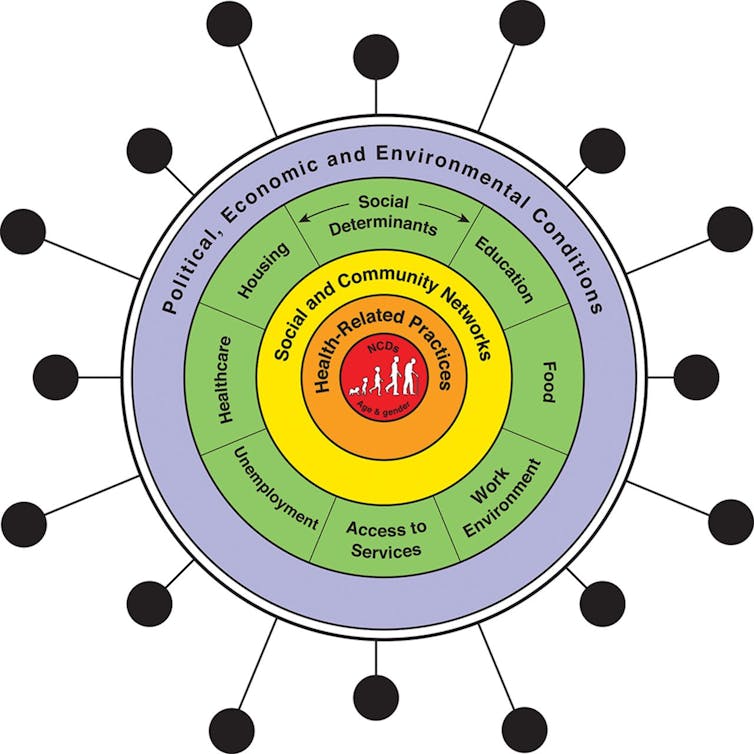

Interactions of COVID-19, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and the social determinants of health. Bambra et al, The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities (2020), Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health

Interactions of COVID-19, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and the social determinants of health. Bambra et al, The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities (2020), Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health

Read more: Overcrowding and affordability stress: Melbourne's COVID-19 hotspots are also housing crisis hotspots

Housing and health are intertwined

Housing affects health in many ways. At the broad scale, housing disadvantage, unaffordable housing and housing of poor quality have been the focus of much recent Australian research. More specific housing drivers of health, such as household mould, injury, overcrowding, noise, cold and damp, have received renewed global attention.

However, capturing the combined health effect of housing is difficult. It’s hard to measure and has many components, and everyone has slightly different housing (and health).

But epidemiologists can provide us with a useful way of estimating the “burden” of various risk factors for population health. Housing risk factors have rarely been examined in Australia, but our estimates flag that the increasing health burden of housing demands attention.

For example, we estimate the health cost (measured in disability-adjusted life years) due to respiratory and cardiovascular disease that can be attributed to mouldy or damp housing is about three times the cost attributable to sugary drinks in Australia. Damp, cold and mouldy housing generates a substantial health burden and could be an easy target for public health prevention strategies. These housing conditions stand alongside many of the classic risk factors such as diet, smoking and obesity.

This estimate of health burden does not even factor in the important role housing plays in mental health. Housing affordability, security, suitability, location and condition are all associated with good mental health.

With rates of eviction likely to increase once moratoriums are lifted across the country, the housing-related mental health burden will almost certainly increase too.

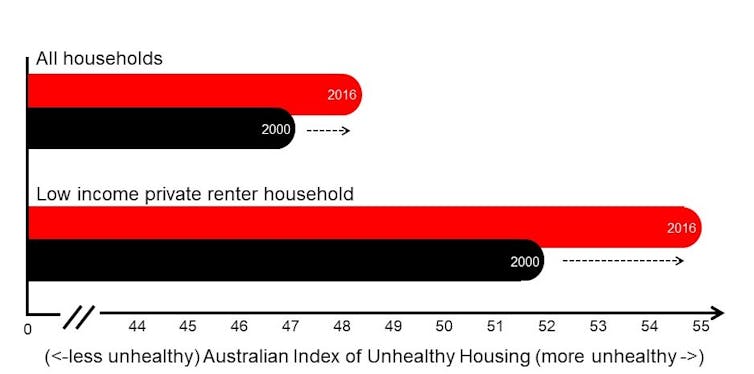

We have previously estimated more than 2.5 million Australians are living in unhealthy housing — and that this number is rising.

The Australian Index of Unhealthy Housing – a composite measure of housing affordability, security, quality, location and accessibility – shows increases in unhealthy housing from 2000 to 2016. Adapted from Baker et al (2019), An Australian geography of unhealthy housing

The Australian Index of Unhealthy Housing – a composite measure of housing affordability, security, quality, location and accessibility – shows increases in unhealthy housing from 2000 to 2016. Adapted from Baker et al (2019), An Australian geography of unhealthy housing

Read more: COVID spurred action on rough sleepers but greater homelessness challenges lie ahead

What housing actions will improve health?

Simple housing-focused interventions could reduce the sizeable health burden from housing-related problems. As the WHO advocates, this requires policy and research that have an eye on both health and housing.

In practical terms, a preventive health strategy would include:

-

minimum rental housing standards to protect occupants’ health, which would target structural factors related to damp and mould, ventilation, heating and cooling, injury hazards, maintenance and repair

-

good-quality public housing that is easy to access as a foundation for healthy lives

-

help with fixing problems, such as mould removal and servicing of heaters, for people in poor-quality housing

-

insulation to maintain indoor temperature and increase energy efficiency.

Poorly insulated housing is a serious health issue in Australia. fizkes/Shutterstock

Poorly insulated housing is a serious health issue in Australia. fizkes/Shutterstock

Read more: Chilly house? Mouldy rooms? Here's how to improve low-income renters’ access to decent housing

COVID adds urgency to rethinking our approach

COVID has caused us to rapidly rethink public housing, nursing homes, share houses and small inner-city apartments. When choosing our current housing, few of us would have factored in the potential for isolation and loneliness, the need for separate working and study spaces, access to private green space, or the infection risk of shared lifts.

The experience of many Australians during the pandemic has almost certainly changed our view of the housing that we need, and what we consider to be healthy. It is time to harness this knowledge and learn from our COVID-19 experience.

Read more: How might COVID-19 change what Australians want from their homes?

Many have lamented the missed opportunity to create economic stimulus in our nation’s COVID recovery plan by building more social housing. But social housing is only a small part of the story. Australia needs to embrace a future where good population health goes hand in hand with good-quality, affordable and secure housing – where health is at the forefront of housing policy and public preventive health strategies harness housing.

7 key questions for a healthy housing agenda

The time is right for Australia to put housing and health in the same room and develop a national healthy housing agenda. Our National Health and Medical Research Council-funded Centre for Research Excellence in Healthy Housing aims to lead and shape this agenda. In doing so, we pose the following questions to our governments, research community and stakeholders:

-

How can we respond in a nationally co-ordinated way to the emerging challenges that COVID-19 presents to healthy housing?

-

Who should be included in the conversation and in developing the agenda – and what is the role of the Commonwealth Department of Health?

-

Where does responsibility for providing healthy housing lie?

-

What is the “minimum standard” of housing that we want to provide to all Australians?

-

What are the healthy housing priorities? Warmth? Mould? Tenure security? Affordability?

-

What groups in our society demand immediate attention? Children? Renters? People with disabilities?

-

How will an Australian healthy housing agenda fit within a national housing agenda (when one exists)?

Read more: Coronavirus lays bare 5 big housing system flaws to be fixed

Rebecca Bentley, Professor of Social Epidemiology, Principal Research Fellow in Social Epidemiology and Director of the Centre for Research Excellence in Healthy Housing in Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne and Emma Baker, Professor of Housing Research and Deputy Director of the NHMRC Centre of Excellence for Healthy Housing

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.