South Australian Home Builders’ Club members at work. SAHBC collection S284, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

Julie Collins, University of South Australia and Lyrian Daniel, University of South Australia

South Australian Home Builders’ Club members at work. SAHBC collection S284, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

Julie Collins, University of South Australia and Lyrian Daniel, University of South Australia

Australians are no strangers to housing crises. Some will even remember the crisis that followed the second world war. As well as producing the popular mid-century modern style of architecture, these post-war decades were a time of struggle.

As the population grew quickly after the war, Australia faced an estimated shortage of 300,000 dwellings. Government intervention was needed. A 1944 report by the Commonwealth Housing Commission stated that “a dwelling of good standard and equipment is not only the need but the right of every citizen”.

A key recommendation was that the Australian government should encourage the building of more climate-responsive and healthy homes.

So, what happened? Why are so many homes today still not well-designed for the local climate?

Australian Architectural Convention Exhibition display pavilion, 1956. Neighbour collection S294, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

Australian Architectural Convention Exhibition display pavilion, 1956. Neighbour collection S294, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

Building small and for a sunny climate

The postwar period was a time of shortages and rationing. As well as meat, sugar, clothing and fuel, building materials were in short supply.

Government restrictions limited house sizes in general to around 110 square metres. That’s less than half the average size of new houses today. Building activity and the prices of materials were also regulated.

While people waited for building permits, many had to arrange temporary housing. Some lived in sleepouts or rented spare rooms from strangers. Others camped in tents or lived in caravans or temporary buildings erected on land bought before the war.

Looking at the published advice on housing design in the 1940s and 1950s, it’s clear passive solar design, small home sizes and climate-responsive architecture were topics of interest. A passive solar design works with the local climate to maintain a comfortable temperature in the home.

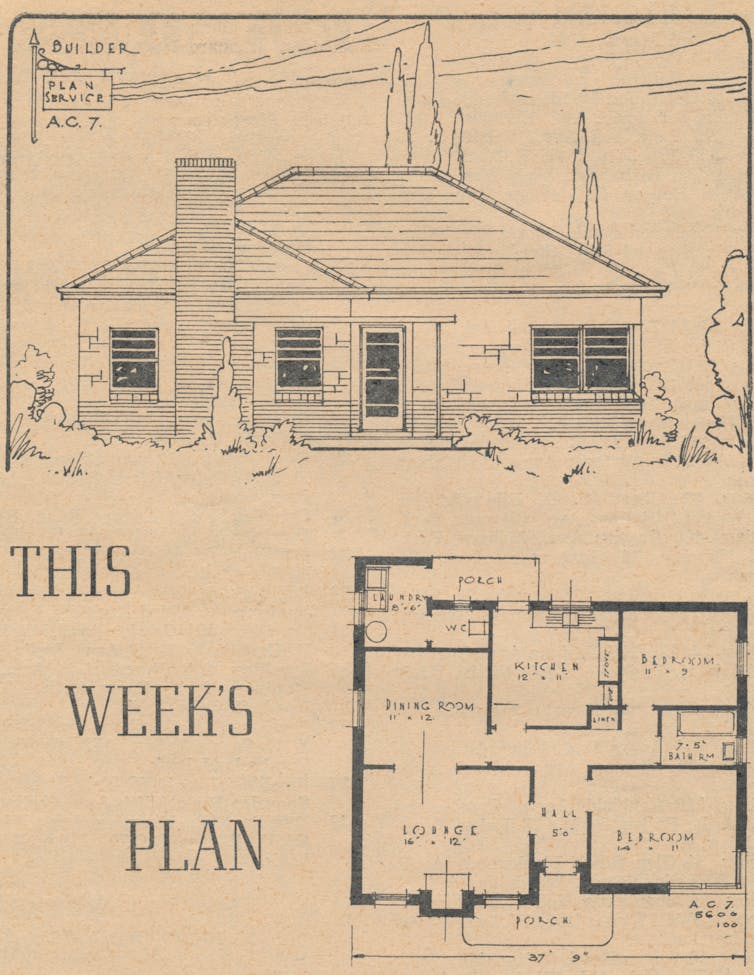

A typical builder’s house plan of the post-war period, ‘This Week’s Plan’ from The Builder, March 20 1953. Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

A typical builder’s house plan of the post-war period, ‘This Week’s Plan’ from The Builder, March 20 1953. Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

This preference was not driven by concerns about climate change or carbon footprints. Rather, the Commonwealth Housing Commission called for solar planning “for health and comfort”.

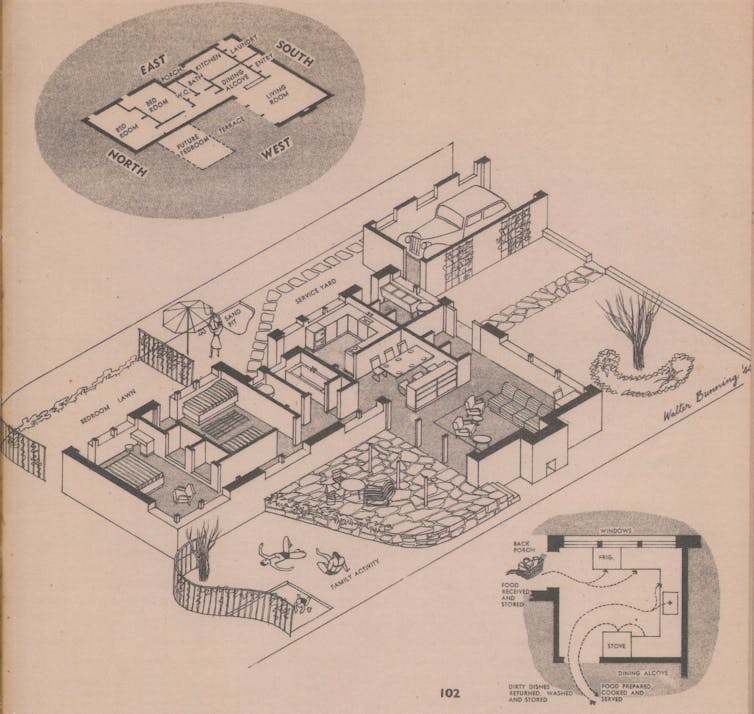

The commission’s executive officer, architect Walter Bunning, demonstrated how to go about this in his book Homes in the Sun. He translated government recommendations into a format appealing to home builders.

This was a time before most home owners could afford air conditioning. It was advised that homes be sited to capture prevailing breezes, have insulated walls and roofs, use window shading and overhanging eaves, and plantings of shade trees and deciduous creepers. External spaces, such as patios, and north-facing living spaces oriented to the sun, were also promoted.

Among the designs were plans for the “Sun Trap House”. This design applied passive solar design principles to a modest freestanding home.

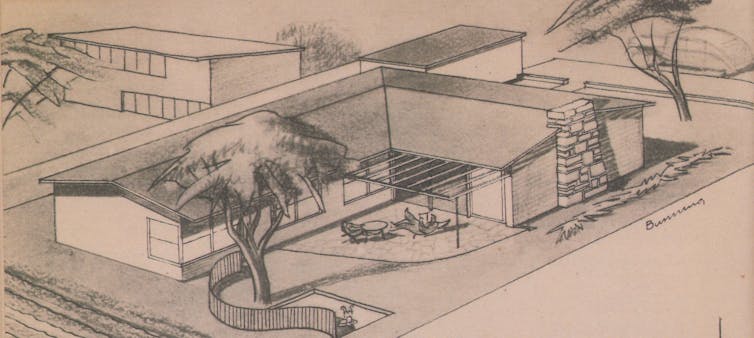

An illustrated view (above) and plans (below) for the Sun Trap House. From Walter Bunning, Homes in the Sun (1945, W.J. Nesbit, Sydney)

An illustrated view (above) and plans (below) for the Sun Trap House. From Walter Bunning, Homes in the Sun (1945, W.J. Nesbit, Sydney)

‘New approach’ didn’t eventuate

Eventually, the housing crisis eased. However, this was not a result of Bunning’s hoped for “new approach to house planning”. Most of the new housing was traditionally designed and built suburban homes.

These came in the form of stock plans by builders and construction companies, with owner builders making up 40% of the homes constructed in 1953-54. Sponsored housing provision programs, including the War Service Homes Scheme and Soldier Settlement Scheme, were rolled out across the country.

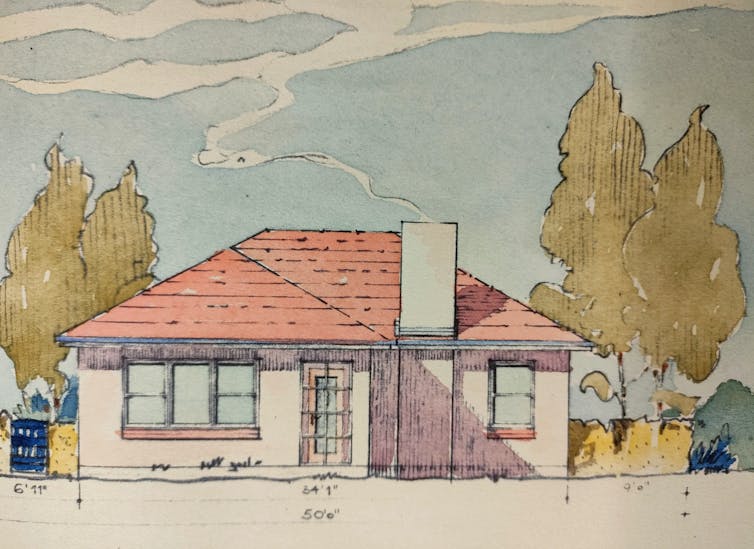

An illustration of a house built under the War Service Homes Scheme. Viney collection S278, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

An illustration of a house built under the War Service Homes Scheme. Viney collection S278, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

At a state level, arms of government such as the South Australian Housing Trust and the Victorian Housing Commission provided not only houses for the rental market but also for purchase. These houses included imported prefabricated dwellings.

Homebuilders Handbook from the Small Homes Service of South Australia, 1953. Cheesman collection S361, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

Homebuilders Handbook from the Small Homes Service of South Australia, 1953. Cheesman collection S361, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

As a result, many homes built in the postwar housing crisis suffer from much the same problems as their predecessors. It led to a situation today where 70% of Australian houses have an energy rating of three stars or lower. That’s well short of the current seven-star standard for new homes.

It wasn’t for lack of architectural advice

In a time of shortage, most people were happy to have a roof over their heads no matter what the design. To architects, this seemed a wasted opportunity.

As a result, the Royal Australian Institute of Architects promoted architect-designed plans that people could buy for a nominal fee. In South Australia, these were available through the Small Homes Service.

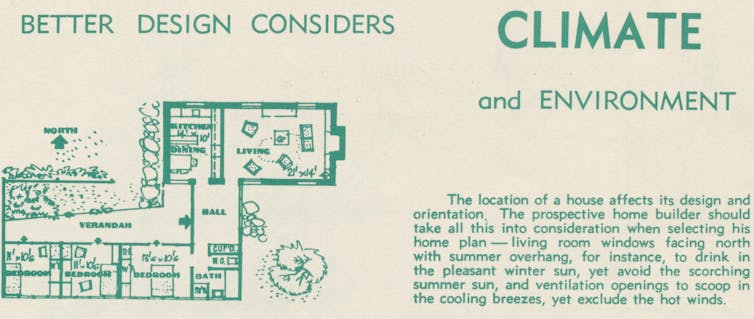

House advice and plans for sale were featured in newspapers and magazines such as the Australian Home Beautiful. The institute also published brochures that promoted the idea that “better design considers climate and environment” and followed recommendations by the Commonwealth Experimental Building Station for maximum comfort.

Architect’s plan from Small Homes Service of South Australia brochure. Cheesman collection S209, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

Architect’s plan from Small Homes Service of South Australia brochure. Cheesman collection S209, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

Passive solar solutions are timeless

The energy-hungry mechanical heating and cooling of today’s houses often neglects passive solar and simple solutions such as insulation, eaves, window awnings, curtains and draught stoppers. These were common solutions in the post-war period.

The principles of passive solar design haven’t changed since then. The ideas advocated both in 1945 and today in design advice such as the Australian government’s Your Home guide to environmentally sustainable homes remain the same.

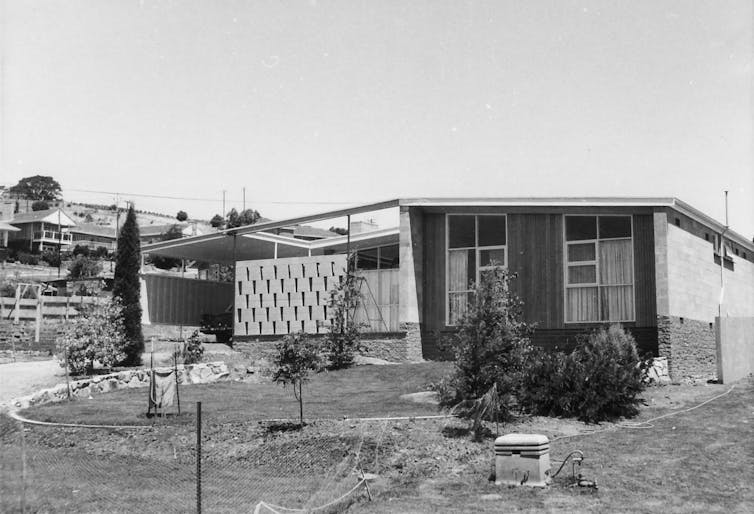

A house built from Plan AC 301 by the Small Homes Service of South Australia, 1959. Tideman collection S307, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

A house built from Plan AC 301 by the Small Homes Service of South Australia, 1959. Tideman collection S307, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia

While our world today faces many crises affecting health, climate resilience, housing affordability and inequality, we have a chance to shape the solutions.

The federal government is developing a National Housing and Homeless Plan and has committed A$10 billion to its housing fund. The target is to build 1.2 million homes over the next five years. What better opportunity to learn from the past and build a brighter, more sustainable future?

Julie Collins, Research Fellow and Curator, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia and Lyrian Daniel, Associate Professor in Architecture, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.