Getty Images

Getty Images

Alex Lo, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington and Faith Chan, University of Nottingham

Two extreme and deadly weather events within the first two months of 2023 have brought the consequences of climate change into sharp focus.

Auckland’s January 27 flood is the most expensive weather event in New Zealand insurance history. Cyclone Gabrielle prompted a national state of emergency, only the third time one has been declared.

Auckland and the upper North Island also face an increasing risk of extreme heatwaves. These floods, storms and heatwaves are becoming more frequent and intense in a changing climate. Our cities, including Auckland, are poorly prepared for what is coming.

Perhaps not surprisingly, there is now a lot more talk about the need for “sponge cities”, with Auckland being a prime candidate. The basic principle is to manage urban flood risks by utilising more natural drainage and flood-resilient systems and material.

The concept is well understood and undoubtedly an appropriate response to current and future conditions – but it is not cheap. Overseas experience, especially in China, suggests building and adapting a city like Auckland to be more “spongey” would require serious financial commitment.

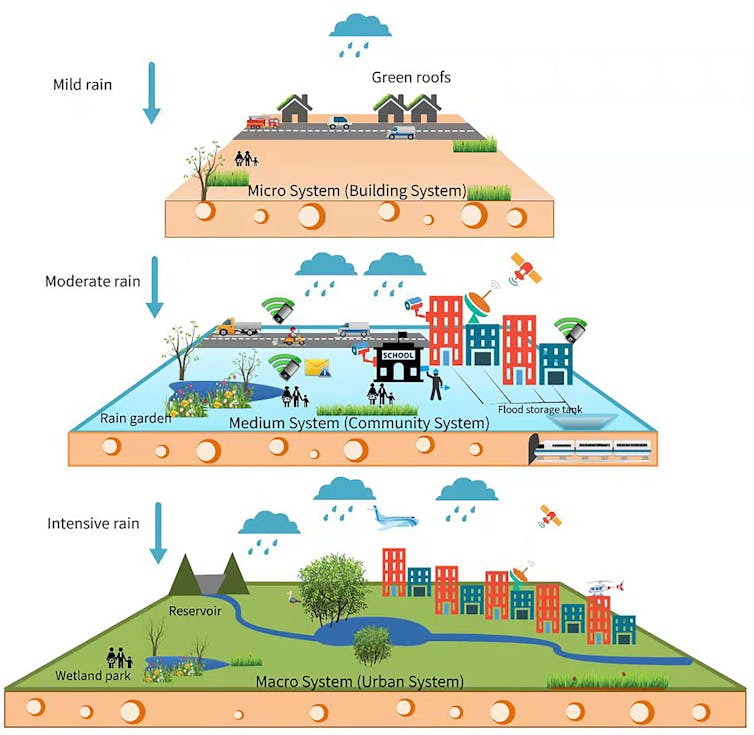

The sponge city operates on a number of levels, each feeding into the next. Author provided

The sponge city operates on a number of levels, each feeding into the next. Author provided

Mimicking nature

The sponge city requires a holistic approach that differs considerably from the way we currently build infrastructure. It involves integrating flood-resilient elements such as bio-swales, pervious pavements, underground water-storage tanks, rain gardens, wetlands and green roofs.

These features can mimic natural hydrological responses and absorb urban stormwater. Increased vegetation and water bodies can also lower ambient temperatures and help people cope with extreme heat.

This type of development is already underway in various places: Australia’s water-sensitive urban design schemes, for example, and the sustainable urban drainage systems and Blue-Green Cities approach in Britain.

Auckland Council has also implemented similar principles, with a good example being the Long Bay residential development, where land use and catchment management planning have been developed simultaneously. Streets are designed to form an integrated “treatment train” for stormwater, involving swales, rain gardens and a wetland at the bottom of the catchment.

In fact, Auckland was recently ranked the “spongiest” of nine global cities, mainly due to its lower urban density and lots of green areas. But this sponginess is clearly still not adequate, as demonstrated by the January floods.

Xinsanjiangkou Park in Ningbo City: sponge city principles in action. Author provided

Xinsanjiangkou Park in Ningbo City: sponge city principles in action. Author provided

Lessons from China

If the sponge city is our goal, we need to see what has been achieved in China, which has been running a large-scale programme for nearly ten years under a nationally coordinated policy. A total of 30 cities participated and provided financial and technical support.

The targets were to increase the area of urban land able to absorb surface water discharges by approximately 20%; to retain or reuse approximately 70% of urban stormwater by 2020; and to reuse up to 80% of stormwater by the 2030s. As well as mitigating flood risk, the programme is about the collection, purification and reuse of urban stormwater to address future climatic extremes (floods and droughts).

The concept requires more than eco-friendly measures for urban water management. A holistic urban development strategy is crucial. Planting more trees, using less impervious surface, and building more green roofs are key elements.

But China’s ultimate goal is to modernise the urban system by creating and reorganising resilient blue-green spaces (rivers, wetlands and trees), with a target of up to 80% coverage in major districts across the selected cities by the 2030s. The estimated construction area in the first 16 pilot sponge cities is more than 450 square kilometres.

Costs and returns

This all requires substantial public investment. The average cost lies between US$14 million and $21 million (about NZ$23 to $35 million) per square kilometre over the first three years of construction and operation. This may be higher in New Zealand due to price differences and inflation.

The Chinese government allocated 400 to 600 million yuan (around NZ$92–$140 million) to each pilot city for the first three years. This was just startup investment – many pilot cities struggled to finance the implementation of their original plans.

An alternative to taxpayer funding might be to encourage public-private partnerships. But private investors in China have shown little interest in financing sponge city initiatives, which are often located in high-risk areas like floodplains. It’s hard to estimate investment returns or guarantee performance in the long time-frame of climate change.

The fact that 19 of the 30 pilot cities have experienced flooding since 2014 is not an encouraging signal, either. In Zhengzhou, one of the pilot cities, nearly 300 people were killed in a catastrophic flooding event in 2021.

There are financial instruments for reducing risk, such as green bonds, green loans and insurance. But a high return is required to cover the risks and costs. Apartments and buildings with green elements are more likely to generate those returns than public parks and underground water-storage systems.

Local solutions

There are other challenges, too. Creating greener, more desirable neighbourhoods can also displace people who can’t afford the price of gentrification.

Auckland has a smaller population and lower urban density than most of the Chinese sponge cities. This means the new infrastructure and developments required would be more spread out across the city.

And Auckland is not like Hong Kong, for example, where a huge underground stormwater storage tank (with a 60,000 cubic metre capacity) has been built. The potential for developing such large and concentrated drainage infrastructure is comparatively limited in a city like Auckland.

New Zealand’s sponge city initiatives would be of smaller scale and more diffuse – as will be the potential benefits. We will need locally adapted solutions and systems – but the lessons and examples from elsewhere can be central to that process.

Alex Lo, Senior Lecturer in Climate Change, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington and Faith Chan, Associate Professor of Environmental Sciences, University of Nottingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.