Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Australia’s population is projected to grow to over 50 million people by 2101. This will have enormous implications for the country’s long-term infrastructure planning and prized livability, particularly in the capital cities where most growth is occurring.

Our recently published research examined ways we can start planning for this doubling of our population now, while we still have time to address it. Our survey asked more than 1,000 people where they think these new Australians should live, to gauge their support for different settlement patterns.

We presumed a net-increase of 28 million people over the next 80 years, with half of those people dispersing across existing Australian cities and towns. We then asked our respondents where would they support the other 14 million people living.

The study is the first of its kind to gauge community opinion on these questions at a national scale.

The Plan My Australia survey.

The Plan My Australia survey.

Not surprisingly, our survey found strong opposition to continued growth of the state capital cities. Instead, our participants showed a strong preference for encouraging people to move to new and expanded satellite cities and rail hubs in regional areas. This finding aligns with the general urban-to-regional migration that was kindled by the pandemic.

Our aim was to understand people’s preferences for managing population growth at the national scale, with the hope it will inform a national urban policy to prepare for the coming population surge.

Where do we want to live?

We devised our settlement pattern scenarios based on possibilities that have been proposed by academics and policy-makers. Here’s how they ranked in order of popularity with our respondents:

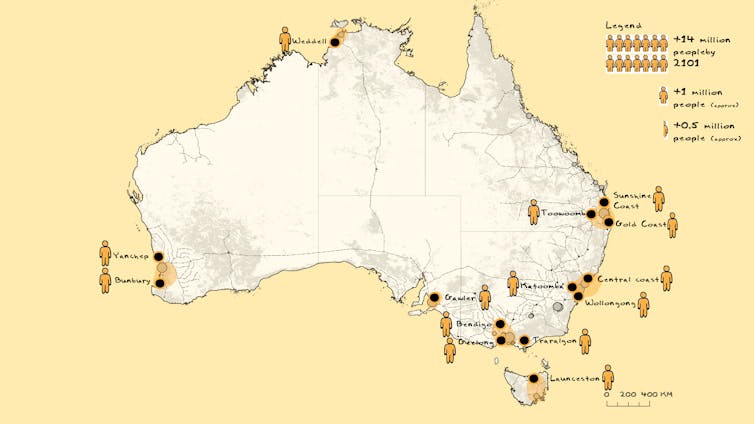

1. Satellite Cities: Due to the affordability and livability issues confronting the state capitals, this scenario siphons long-term population growth to 14 satellite cities like Gold Coast, Geelong and Wollongong. Respondents considered this scenario to be the most sustainable and feasible, while also ensuring livability.

Satellite Cities.

Satellite Cities.

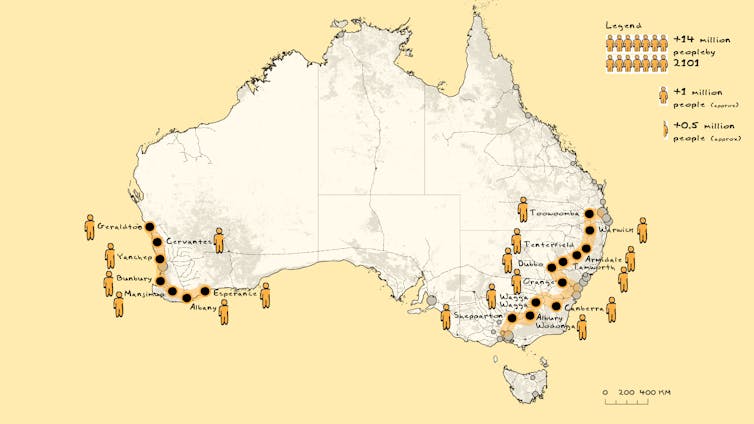

2. Rail Cities: Inspired by rail hubs in other countries, this second placed scenario funnels population growth to 18 regional cities connected to the state and federal capitals by major high-speed rail links (yet to be built).

Rail Cities.

Rail Cities.

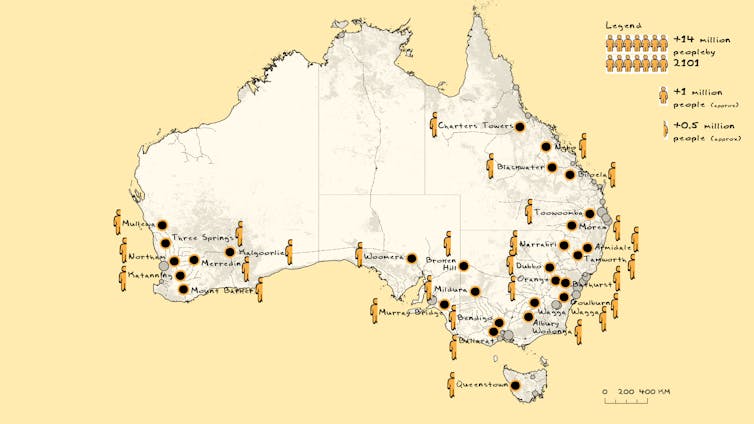

3. Inland Cities: This scenario distributes population growth to 29 key inland centres, many with at least hypothetical capacity to take on more people.

Inland Cities.

Inland Cities.

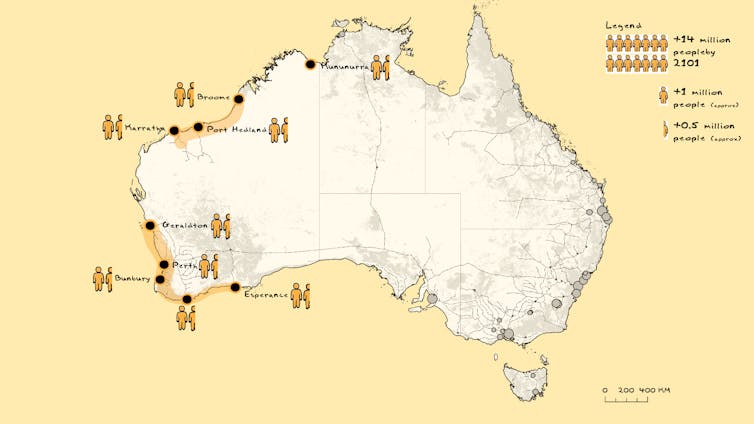

4. Western Cities: Western Australia comprises one-third of the continent but houses just over one-tenth of the population. Accordingly, this scenario boosts the populations of nine cities and towns along the west coast.

Western Cities.

Western Cities.

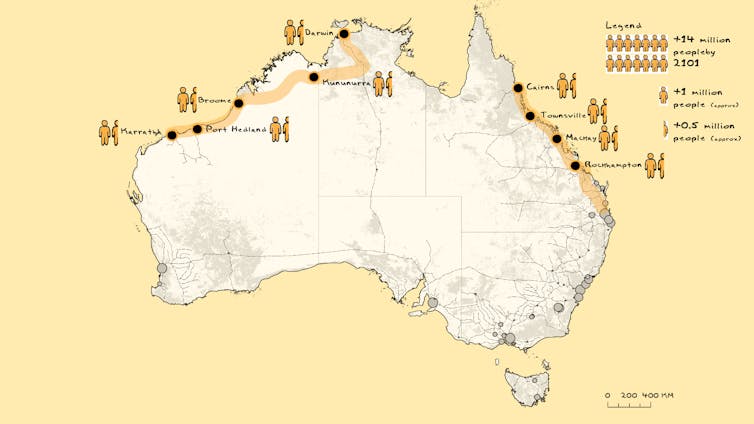

5. Northern Cities: Given northern Australia’s considerable economic output and proximity to Asia, this scenario envisions an increase of the population of the nine largest northern cities.

Northern Cities.

Northern Cities.

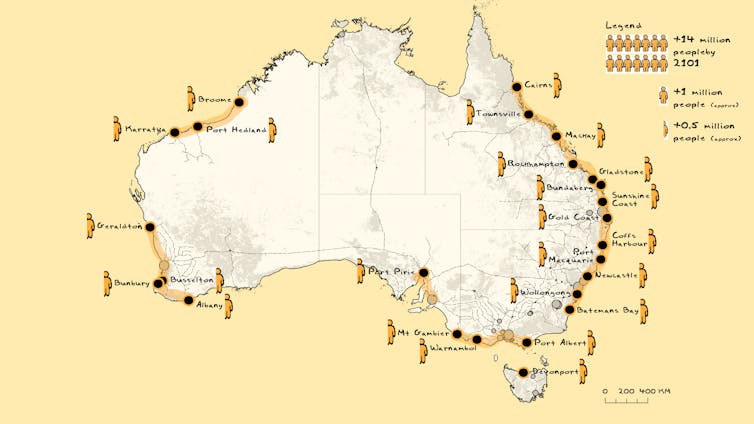

6. Sea Change Cities: Given the ever-escalating costs of coastal real estate in the capitals, this scenario channels population growth to 25 alternative sea-change cities.

Sea Change Cities.

Sea Change Cities.

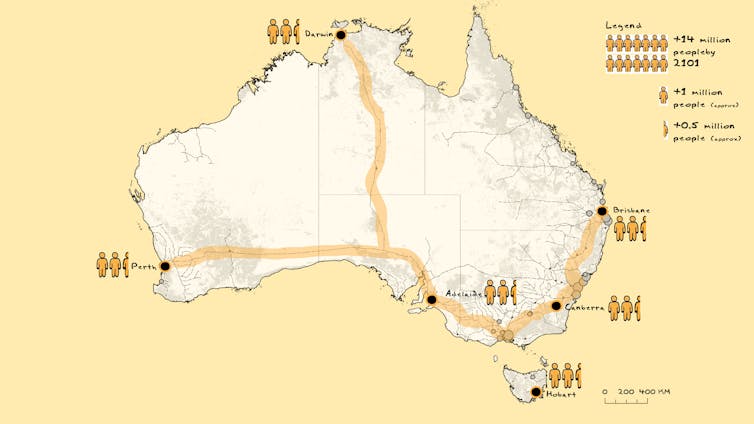

7. Secondary Capital Cities: Given the livability and affordability issues in Sydney and Melbourne, this scenario sees more people moving to the smaller state and territory capital cities.

Secondary Capital Cities.

Secondary Capital Cities.

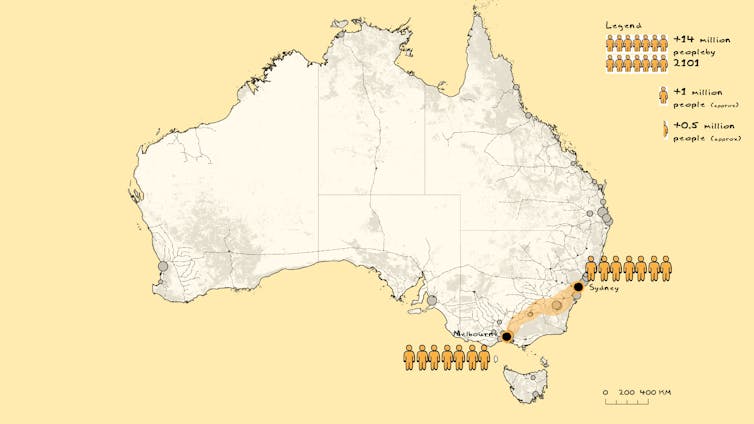

8. Megacities: Melbourne and Sydney generate the bulk of Australia’s GDP and historically have attracted the most migrants. This lowest-ranked scenario would see this trend continue with concentrated population growth in two future Australian megacities. Respondents universally loathed this scenario.

Megacities.

Megacities.

Why satellite and rail hubs are so appealing

As the rankings show, Australians generally support population decentralisation away from state capitals (in particular Melbourne and Sydney) with the expansion of satellite and rail cities.

Such sentiments could stem from a case of national-scale NIMBY-ism (“not in my backyard”). However, over a third of our respondents were from regional and remote areas, and most of these people supported population growth in their home towns.

We argue that expanding satellite and rail cities is a smart plan for the future because it can achieve equitable distribution of population growth and protect urban livability. Moreover, these schemes allow for better adaptation to climate change by generally avoiding coastal areas that are vulnerable to sea-level rise.

However, expanding regional centres into major cities comes with considerable challenges, such as attracting industries and jobs away from the capital cities, delivering the crucial enabling infrastructure of ports, airports, rail lines, schools, housing and medical centres, and overcoming environmental challenges like water security.

Why we need a national urban policy

This type of ambitious planning requires a national urban policy, which is currently lacking in Australia. Our current population planning is too fragmented and uncoordinated, with states, territories and local governments all having divergent views about our common future. It resembles a patchwork quilt.

As we emerge from the disruptive restrictions caused by the pandemic, which led many to embrace tree- and sea-change moves away from the capitals, there’s no better time to pursue such a coordinated national plan.

There’s already some semblance of political will. The Coalition has spruiked policies for “smart cities” and negotiating “city deals”, which unite local, state and federal governments on key projects. Labor, meanwhile, is fixated on building high-speed east coast rail.

With an election looming, will either party take a harder look at the bigger question here and announce plans for a national urban policy? We can’t pretend this population boom isn’t happening – and our cities need to be ready.

Julian Bolleter, Deputy Director, Australian Urban Design Research Centre, The University of Western Australia and Robert Freestone, Professor of Planning, School of Built Environment, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Linkedin