Renters in Victoria soon won't have to deal with dodgy heaters and insulation. Now other states must get energy-efficient

Renters will no longer have to contend with poorly insulated homes and Victoria will move closer towards 7-star home efficiency standards under a A$797 million plan announced this week. It’s purportedly the biggest energy efficiency scheme in any Australian state’s history.

Renters will no longer have to contend with poorly insulated homes and Victoria will move closer towards 7-star home efficiency standards under a A$797 million plan announced this week. It’s purportedly the biggest energy efficiency scheme in any Australian state’s history.

Energy efficiency essentially means using less energy to perform the same job. It’s often the quickest and cheapest way to reduce emissions from energy use, yet state and federal governments in Australia have traditionally done little to seize the opportunity.

Australia’s national energy productivity plan, agreed by the nation’s energy ministers in 2015, has stalled. It aims for a 40% improvement in energy productivity by 2030, but has so far achieved only a fraction of that.

It’s clearly time to kickstart the energy efficiency revolution in Australia – to reduce energy bills, make homes more comfortable and meet our climate goals. So let’s examine Victoria’s plan, and how other states might follow.

Better homes, lower bills

The Victorian package is strongly focused on helping renters and low-income households in existing homes, and forms part of the state’s 2020-21 budget.

The measures include:

-

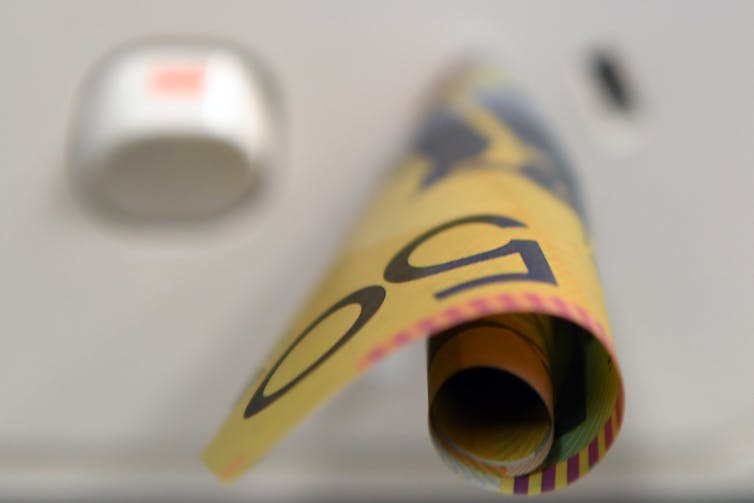

A$335 million to replace old wood, electric or gas-fired heaters with more efficient systems. The program will be open to low-income earners

-

A$112 million to seal windows and doors, and upgrade heating, cooling and hot water in 35,000 social housing properties

-

minimum efficiency standards for rental properties, expected to benefit renters living in around 320,000 homes with poor heating and insulation

-

funding to help Victoria move to 7-star efficiency standards for new homes

-

a A$250 payment for those struggle to pay their bills

-

A$14 million to expand the Victorian Energy Upgrades program, including rebates for “smart” appliances.

The package follows a A$5.3 billion announcement earlier this month to build 12,000 new social and community housing units over four years. These new homes will meet a 7-star energy rating, rather than the mandatory 6 stars.

A new approach

To date, energy efficiency policies and programs in Australia have mostly focused on new and owner-occupied homes. These homes are easy targets, because they’re on separate titles and don’t involve negotiations with owners’ corporations or landlords.

So Victoria’s program helps to fill a big gap. Currently, the average Victorian home has a 3-star energy rating, so there is plenty of room for improvement in existing homes. The approach will ensure renters, and those in homes already built, see the benefits of energy efficiency. And it means emissions reductions are realised across the residential sector.

In the past, policy in this area has largely been debated on narrow economic assessments of “cost effectiveness”. And in my experience, powerful industry groups and political agendas seek to slow progress behind closed doors, while consumers often lack a voice in decision-making.

Both the Victorian government announcement, and progress at the COAG level, follow advocacy from social justice groups and Energy Consumers Australia (ECA) building on academic research (eg https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/338 ). These groups have helped highlight how poor housing affects vulnerable people, causing high energy bills and health problems.

Read more: Australia has failed miserably on energy efficiency – and government figures hide the truth

In February 2019, COAG agreed to a national plan towards zero-net-energy new buildings for Australia. In November that year it resolved to extend the plan to existing homes. Proposed measures include national frameworks for use by states and territories, covering energy disclosure at the time of a home’s sale or lease, and minimum energy efficiency requirements for rental properties.

Victoria’s commitment this week to introduce minimum energy standards for rental properties puts it at the forefront of this process.

The Victorian government had earlier developed a Residential Efficiency Scorecard suitable for rating homes under an energy disclosure scheme assessment tool. So far it’s been rolled out as a voluntary scheme and been trialled in other states.

In Melbourne, a 7 star building would require around 25% less heating and cooling energy than a 6 star home.

Of course, the devil is in the detail. When will energy disclosure and rental energy standards be introduced? How stringent will the standards be? Will there be sufficient focus on improving summer performance to cope with climate change? Will old gas appliances be replaced by alternatives that use renewable electricity? How much of the package will be implemented before Victoria’s next election in late 2022? Time will tell.

Time to get on board

Other Australian states and territories, including NSW, the ACT and South Australia, have introduced impressive energy efficiency measures. The ACT, in particular, has had a mandatory energy disclosure scheme at time of sale for many years. And NSW is introducing a scheme to encourage a reduction in peak electricity demand.

Action by individual states and territories may encourage other jurisdictions to follow. However different energy efficiency approaches across states may dilute benefits while increasing confusion among households and complicating life for industry. This must be guarded against.

In June, the International Energy Agency released a global “green recovery” plan to help economies recover from the pandemic. Many of the millions of new jobs created through the plan would be in retrofitting buildings to improve energy efficiency. Increasing energy efficiency would also improve electricity security, lowering the risk of outages.

But globally, improvements in energy efficiency have slowed in recent years, making it harder to curb climate changes. The federal government, so far fixated on a “gas-led” path out of recession, must also get on board the energy efficiency wagon.

Alan Pears, Senior Industry Fellow, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles