Surry Hills: Once the centre of New South Wales’ ‘rag trade’

Sydney has awoken to the smouldering ruins of its largest city fire in 55 years. The “abandoned building” in Randle Street, Surry Hills, adjacent to Central Station was once the R.C. Henderson Ladies Hat factory, a six-storey brick structure built in 1912.

Peter McNeil, University of Technology Sydney

Sydney has awoken to the smouldering ruins of its largest city fire in 55 years. The “abandoned building” in Randle Street, Surry Hills, adjacent to Central Station was once the R.C. Henderson Ladies Hat factory, a six-storey brick structure built in 1912.

Empty for some time, the space was slated to become a boutique hotel. Full of wooden trusses and likely old machinery oil, the building collapsed in a spectacular bonfire.

How did Surry Hills come to be the centre of the fashion manufacturing industry, or “rag trade”, for New South Wales?

Dressing in New South Wales

Ready-made clothing developed in 1860s Australia with the uptake of Isaac Singer’s sewing machine. As the population became more prosperous, it needed better clothes.

The New South Wales fashion industry was one of the most locally concentrated in Australia. Apart from some large men’s suiting and shirt factories, most men’s, women’s and children’s clothes and hats were made in or near Surry Hills.

Electric-powered machines that sped up production were introduced from 1914.

David Jones assembled its garments in a modern purpose-built factory in Marlborough Street, Surry Hills in 1915.

Until the 1980s, most Australians wore Australian-made clothes. High import duties meant there was enormous impetus for local production. Although many women made their own clothes, they rarely made men’s outer clothes.

As more women worked, they had less time and needed to buy store-bought clothes.

From 1928-68, the clothing and footwear sector was marked by small plants, low levels of capital investment, a rate of profit nearly 65% above the average for all industries, high risk, uncertainty and, of course, regularly changing fashions.

As a result, the industry favoured those with fashion and style knowledge: skilled owner-managers who understood craft skills and production. In 1939, 94% of establishments were operated by working proprietors.

Personal interactions between boss and worker were close. The shop floor was often set up as a “family”, with all the tensions that entails.

The large CBD retailers enjoyed close relationships with the manufacturers. Buyers made frequent visits, sometimes daily.

In the 1940s, half of the women working in manufacturing in Sydney were working in the rag trade.

The look and feel of Surry Hills

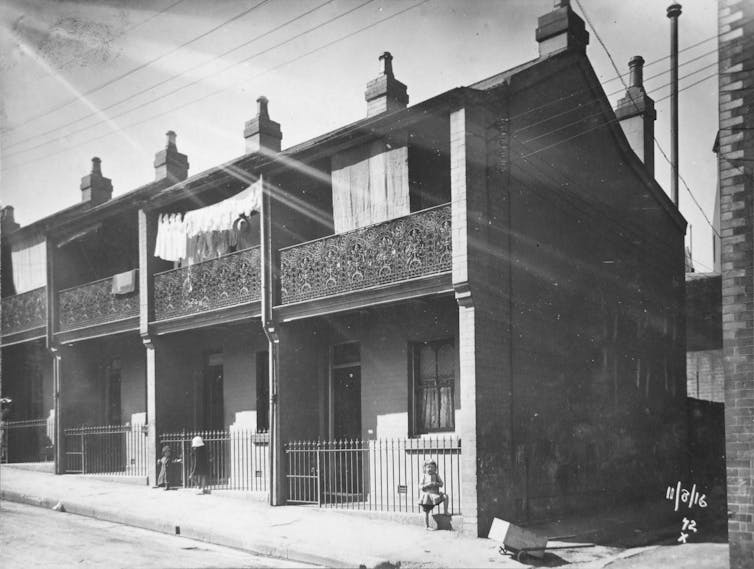

Surry Hills was covered in cheap terrace houses built as worker’s rentals from the 1850s. The new Central Station opened in 1906 on the site of a former cemetery.

As the terraces deteriorated, the area was widely considered a “slum”, finely captured in Ruth Park’s novel The Harp in the South (1948).

Multi-storey factories allowing for multiple occupancies were the norm.

Women’s fashion was made in small batches with frequent variation. The goods were light and compact, meaning lifts and staircases could be used for deliveries. Equipment used in the industry was also light and easily installed on floors above ground level.

Surry Hills was the main buying centre for fashion; department store, suburban and country buyers would walk from factory to factory to inspect the goods.

Labour for the Surry Hills industry was drawn from the entire metropolitan area. Women immigrants made up 70% of employees.

Labour became less skilled as detailed hand-tailoring and dressmaking were superseded by machines in the 1950s.

Post-war Surry Hills

Between 1947 and 1966, 1.8 million migrants arrived in Australia.

Many worked in factories. A large proportion of the Jewish Europeans who arrived in the 1930s and 1940s worked in the clothing industry; in turn they employed many southern-European migrant women who arrived with little or no English.

Fashion and clothing knowledge enabled many Jewish migrants to re-establish their livelihoods and identities across the globe. Between 1938 and 1961, Sydney’s Jewish population doubled.

Low rents due to deteriorating building stock and the lack of demand for office space in Surry Hills meant clothing manufacturing continued. Factory buildings replaced some terrace houses from 1958, when Surry Hills was zoned for “B class” industry.

European Jews, mainly from Poland and Czechoslovakia, acquired old properties and redeveloped them as two-storey factories. The owners occupied only a portion of the building and rented out the remaining space to fellow countrymen. The capital required to enter the industry was small; machines could be hired and floor space rented on a weekly basis. The average Sydney clothing factory employed 15 workers.

The number of married women working in Australia rose to around 30% by 1966. Fewer had time to do home sewing. This created opportunities for cheaper ready-to-wear lines that could keep pace with rapid fashion changes.

The household spend on clothing, footwear and drapery climbed dramatically, tripling from 1946 to 1960.

The shift to this ready-to-wear trade was amplified by Jewish entrepreneurship and retailing. Jewish migrants introduced new and brighter colours into everyday clothing. They helped to create the demand for lighter clothes, such as finely knitted garments of contemporary European fashion, modern lines in coats, and the Swiss machine-lace that adorned the short mod-dresses of the 1960s.

End of the rag trade

The Whitlam Government cut tariffs by 25% in 1973 to reduce inflation and as a new approach to national industry planning. At the time, fashion amounted to 10% of Australia’s total manufacturing employment.

The reduction of tariffs and subsidies, price gouging, discounting and off-shore production decimated the industry. Employment fell by nearly one third in two years after 1973. The market share of imports doubled. Business people moved their capital from manufacturing into property.

Clothing production moved to areas such as Marrickville, with Vietnamese entrepreneurs and workers replacing the Greeks who had once worked in the trade there. By 1985, one third of workers in the local clothing industry were Asian.

If we time travelled back to 1950 in Randle Street, the scene would be very different from today.

Rather than urban professionals and baristas, we would see rag trade seamstresses, finishers, designers, managers, retailers, salespeople and promoters.

We might see bundles of the new synthetic corded fabrics, satin lastex miracle yarn, sanforised shrunk fabrics and fiesta nylons. Or reps showing the new Goldner Triflex zipper, Perkal brothers shoes, Rain'N Shine coats, or Hestia bras.

We would see many of Sydney’s 9,000 workers in clothing and tailoring, 4,300 in dress and hat-making, and 8,000 in shirt-making who spent their working lives in Surry Hills. With this fire, another piece of Sydney’s rag trade and workers’ history is lost.![]()

Peter McNeil, Distinguished Professor of Design History, UTS, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles