Shutterstock

Shutterstock

As more and more Australians are forced into private renting, including Australians who once would have owned homes or lived in social housing, more are living in poverty, suffering financial stress and becoming homeless.

Social housing – where rents are typically capped at 25% of tenants’ incomes – used to make a big difference to the lives of many vulnerable Australians.

Infrastructure Victoria has found that it makes a big difference to homelessness. Only 7% of renters in social housing subsequently become homeless, compared to 20% of private renters.

But the stock of social housing – currently around 430,000 dwellings – has barely grown in 20 years, during a time Australia’s population has grown 33%.

Given that most social housing tenants stay for more than five years, the stagnating stock of such housing means there are few openings available for people whose lives take a turn for the worse.

We not only have fewer social houses per person, we also have vastly fewer openings for anyone looking.

The fund would leverage cheap money

Social housing is expensive. The capital cost per unit over and above what is recouped in rent amounts to about A$300,000.

A new Grattan Institute paper released on Monday makes the case for a $20 billion federal government Social Housing Future Fund, which would make regular capital grants to state governments and community housing providers.

Future funds are not unusual. The Future Fund Board of Guardians, chaired by former Commonwealth Treasurer Peter Costello already manages $247.8 billion in assets across six funds addressing problems ranging from covering federal public servants’ superannuation entitlements to drought to disability care to medical research.

Peter Costello chairs the Future Fune Board of Guardians. Dean Lewins/AAP

Peter Costello chairs the Future Fune Board of Guardians. Dean Lewins/AAP

The endowment for the Social Housing Future Fund could be established by borrowing at today’s ultra-low interest rates. Some states, including Victoria, NSW, and Queensland already operate social housing investment funds, some financed by privatisations, others financed by government borrowing.

The funds would be managed by the existing Future Fund Board of Guardians with only the returns above inflation used to provide capital grants for housing, maintaining the real value of the fund over time.

Capital grants for new social housing units would be allocated by the existing National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation via competitive tenders after specifying dwelling size, location and subsidies for tenants.

As is the case with the existing Future Fund, the funding would be off budget, with only each year’s profits or losses affecting the budget balance.

The extra $20 billion in gross government debt would be small compared to the nearly $1 trillion currently on issue, supported by about $500 billion a year in federal government revenues.

How much could a $20 billion fund support?

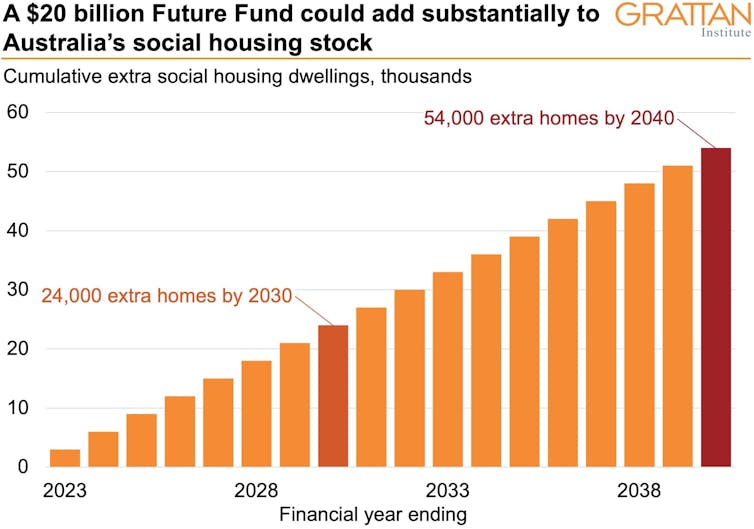

A $20 billion fund that achieved after-inflation returns of 4-5%, could over time provide $900 million each year – enough to deliver 3,000 extra social housing units a year in perpetuity, assuming capital grants of $300,000 per dwelling.

Starting in 2022-23, the fund could build 24,000 social housing dwellings by 2030, and 54,000 by 2040. Future governments would be at liberty to top up the fund, helping expand the social housing share of the national housing stock.

Assuming $300,000 capital grant per dwelling, indexed to inflation. Source: Grattan analysis

Assuming $300,000 capital grant per dwelling, indexed to inflation. Source: Grattan analysis

The Labor Party has proposed something similar, in which funds are used for annual service payments to community housing providers rather than via upfront capital grants.

The on-budget cost of our proposal would be modest: about $400 million a year, or less than 0.1% of federal government spending in the form of interest costs.

Alternatively, part of the above-inflation return from the fund each year could be used to cover these costs, leaving $500 million available to fund the construction of nearly 1,700 new social housing units per year with no hit to the budget.

The Commonwealth should require state governments to match its contributions.

States could double the money

Any state that did not agree to provide matching contributions would be ineligible for capital grants for social housing in that year, with the savings reinvested in the Future Fund and distributed across all states the following year.

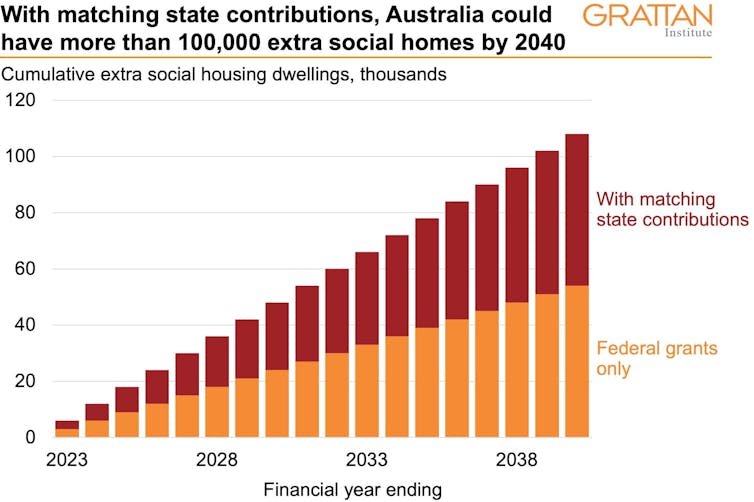

If matched state funding was forthcoming, the fund could provide 6,000 social homes a year – enough to stop social housing shrinking as a share of the total housing stock.

This would double the build to 48,000 new homes by 2030, and 108,000 by 2040, boosting the current stock by one quarter.

Assuming $300,000 capital grant per dwelling, indexed to inflation. Source: Grattan analysis

Assuming $300,000 capital grant per dwelling, indexed to inflation. Source: Grattan analysis

By itself, a Social Housing Future Fund wouldn’t solve the housing crisis for low-income Australians. We would still need to boost rent assistance for people on income support and do more to boost housing supply to bring rents down.

But it would give a much-needed helping hand to some of our most vulnerable, and keep social housing there for future generations should they need it.

Brendan Coates, Program Director, Economic Policy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.