Authors supplied

Authors supplied

The design and construction of new homes in Australia may leave residents vulnerable to heatwaves and local councils can do little to fix the situation, our new research has found.

Our study focused on the Jordan Springs development at Penrith in Western Sydney. We found the estate may not be fit to withstand future heatwaves, potentially putting residents at risk and leaving them dependent on increasingly expensive air conditioning.

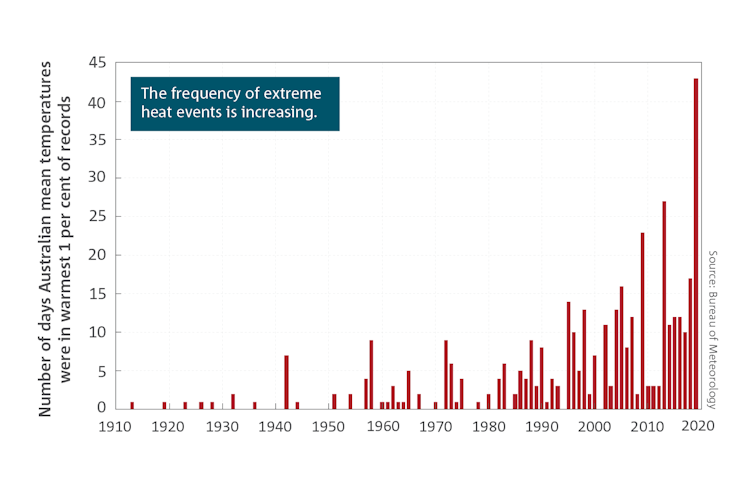

Australians are already experiencing significant heatwaves. And the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change this month warned heatwaves will become even more frequent, intense and longer.

Rising house prices in Australia’s major cities are driving many people to more affordable housing estates on the city fringe. But without interventions from state governments and local councils, such estates may be unsustainable as heatwaves intensify.

Exacerbating hot temperatures

Jordan Springs is a ten-year-old planned housing estate located 7km from Penrith. As of the 2016 Census, the estate was home to 5,156 residents. It currently consists of 1,819 homes and it is forecast to grow to about 13,000 residents in 4,800 homes.

Our research involved:

- collecting secondary information about the area, including climate forecasts, regional growth forecasts and planning law

- conducting surveys and interviews with residents, government and council officials and scientific experts

- examining the estate’s physical exposure to heat through aerial imagery and ground cover analyses.

Inland suburbs are significantly hotter than those on the coast, due to the lack of cooling coastal breezes. That is true of Penrith, which lies 60km west of Sydney’s central business district. On average, Penrith experiences three times more days above 30℃ than the CBD.

Jordan Springs is compliant with building regulations and individual homes are compliant with NSW’s Building Sustainability Index (BASIX). However, we found the estate’s built environment exacerbates the region’s hot temperatures and exposes residents to higher indoor temperatures. This points to a need for better planning regulations and building design.

We suspect our findings may be true for other planned estate developments across New South Wales and Australia, but more research is needed to confirm this.

Read more: Houses for a warmer future are currently restricted by Australia's building code

The study focused on the Jordan Springs housing estate in Western Sydney. Source: Lend Lease

The study focused on the Jordan Springs housing estate in Western Sydney. Source: Lend Lease

What we discovered

Homes in the estate are built close together, with minimum side and rear distances from adjoining properties of 1.8m and 6m respectively. This can prevent air flow and allow heat to accumulate during the day. The close proximity also reduces space for vegetation.

The estate’s streets are wide and buildings are low. This reduces shade and maximises exposure to the sun of roofs, roads and other hard surfaces.

Almost 59% of Jordan Springs is heat-trapping hard surface cover such as concrete and asphalt. This compares to just 10% combined tree and shrub cover. A lack of greenery can contribute to the accumulation of heat.

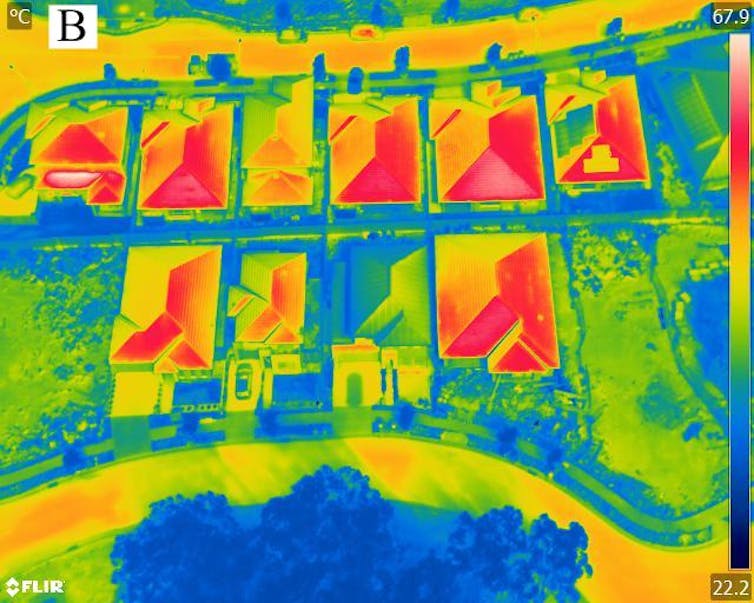

Houses, roofs, and surrounding surfaces (such as roads, walls and fences) are generally dark-coloured, which increases heat absorption. For example, dark roofs have been recorded as 20-30℃ hotter than light coloured roofs (see images below).

A variety of dark and light coloured roofs. Sebastian Pfautsch

A variety of dark and light coloured roofs. Sebastian Pfautsch

Thermal imagery shows the dark roofs are significantly hotter than light ones. Sebastian Pfautsch

Thermal imagery shows the dark roofs are significantly hotter than light ones. Sebastian Pfautsch

The NSW government last week recognised the problem dark roofs pose in hot weather, announcing light-coloured roofs will be mandatory in new homes in parts of southwest Sydney.

At Jordan Springs, we found some houses were poorly insulated and draughty. Yet many of these homes still attained a high BASIX star rating for energy efficiency.

The Conversation sought a response from the developer, Lend Lease. A company spokesperson said given the technical nature of the findings, it could not provide an adequate comment by deadline.

Read more: Buildings produce 25% of Australia's emissions. What will it take to make them 'green' – and who'll pay?

A persistent problem

During heatwaves, the built environment can exacerbate already dangerous conditions for humans. Many people turn on their air conditioners to beat the heat, increasing energy use and leading to higher electricity bills.

So why does this situation persist?

One councillor believes the profit imperative of developers is a factor, telling us:

the developers are only thinking about their shareholders and directors … I don’t believe that the developer is eco-friendly.

Meanwhile, a scientific expert said:

Today people don’t build double brick because of the cost […] they are about building fast and moving on and building more because of the profit they make […] everything must be cheap or else you can’t be fast.

In recent years there have been media reports of private certifiers signing off on buildings which do not meet planning guidelines. One local councillor told us this can result in homes that don’t perform well in hot weather.

And even if councils could enforce stricter rules, they risk losing interest from developers – and associated financial benefits. A frustrated council official said if one council had strict rules around housing developments and heat, and the neighbouring council did not, then:

developers are more likely to go there to build housing … It’s a tricky balance. We still want growth, and we want to work with developers, but we want to improve how we are doing things.

Councils wanting to impose stricter planning rules fear loosing developments to neighbouring councils. Shutterstock

Councils wanting to impose stricter planning rules fear loosing developments to neighbouring councils. Shutterstock

So where to now?

Clearly, many planned housing estates are not fit-for-purpose in our changing climate. But residents can take action to help their homes and estates stay cooler in hot weather.

Where possible, install heat-resistant features such as blinds, shades and awnings to increase passive cooling and reduce air conditioning dependence. Plant trees and shrubs in home gardens and encourage communities to engage in estate-wide greening initiatives.

Councils and developers should ensure prospective residents understand the benefits of light-coloured materials, passive design and urban green space. This will encourage them to make more informed decisions during the construction process.

But ultimately, the responsibility to ensure the heat-resilience of current and future housing rests with state governments and developers. While building new homes and returning profits is important, the well-being of citizens in a warmer world must be the paramount concern.

Read more: The world endured 2 extra heatwave days per decade since 1950 – but the worst is yet to come

Victoria Haynes, Research Officer, University of Sydney; Dale Dominey-Howes, Professor of Hazards and Disaster Risk Sciences, University of Sydney, and Emma Calgaro, Research Associate, Sydney Policy Lab, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.