Social housing is part of the lives of a surprising number of Australians. On any one night in Australia, just over 4% of households rent social housing. Yet it has housed many more people than this for brief, and sometimes repeated, periods. We estimate up to 10% of Australians have called social housing home at some time in the past 20 years.

Throughout the postwar era, Australians have used social housing in various ways. Social housing can be:

-

a place to raise a working family

-

a “springboard” to owning a home

-

a brief “safety net” to escape domestic violence

-

a stable home following homelessness.

Read more: As simple as finding a job? Getting people out of social housing is much more complex than that

Today the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) releases a major commissioned study tracking the pathways of people into and out of social housing from 2000 to 2015. Our analysis, using national data, provides many interesting insights into how Australians use social housing.

Try to picture a “typical” social housing tenant. You might imagine a single mother, or an elderly lady who has lived and raised family there. Or do you see a single man who has fallen out of the workforce? Regardless of whom we picture, most of us will probably see social housing as an end-point in their housing journey – a stable home.

The truth is Australians use social housing in several very different ways. A home for life is just one of those ways.

Who uses social housing?

When we look over time (in this case 15 years) at everyone who has lived in social housing, we find only about a third of people lived continuously in the tenure. Almost another third entered social housing in that time and remained there. But a surprisingly large proportion entered and left the sector either once or multiple times.

So social housing represents different things – a long-term home, a springboard, a safety net – to different people.

Read more: Is social housing essential infrastructure? How we think about it does matter

The likely role of social housing depends a lot on what else is going on in people’s lives. When we compared characteristics of all people who were “social renters” at some time in the 15 years, we found:

-

the group who lived continuously in social housing were generally older (average age 60) and more likely to be female than people on other housing pathways, with age pension and disability benefits the most common types of government assistance received

-

those who left social housing (and never returned) were the second-oldest group (average age 50), also predominantly female, with unemployment and disability support the most commonly received government assistance

-

the group who entered (and then remained in) social housing was distinct in its high proportion of refugees and other people born overseas, with unemployment and disability support again the most common government assistance

-

more than a quarter of all pathways could be described as more transitory, involving multiple entrances or exits. This group as a whole was younger, more likely to be Australian-born and more likely to be Indigenous than the other groups. It was also distinct in the dominance of unemployment benefits among the forms of government assistance received.

Social housing has broad benefits

The people who enter social housing, and their patterns of behaviour, are nowhere near as predictable as many of us thought. There are many pathways. Only about one-third are long-term tenancies.

Despite the shrinkage of this sector, and a relative lack of investment in it, social housing does much more than simply house the elderly, sick and most disadvantaged people in our society.

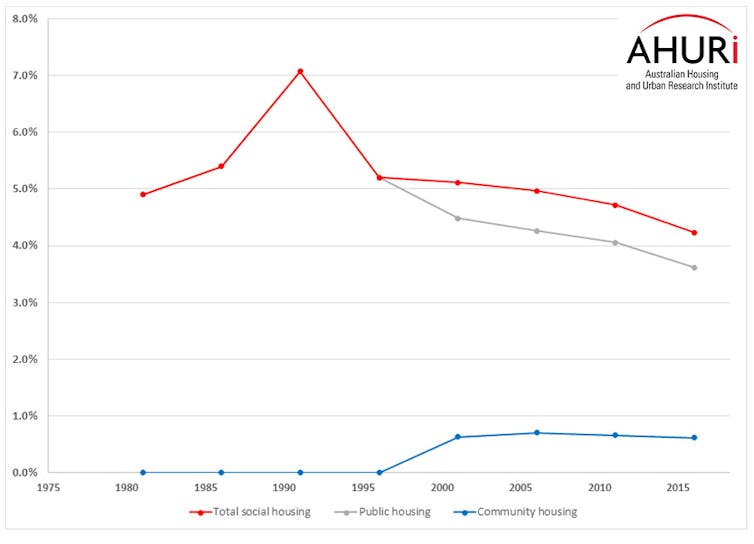

Social housing (public and community housing) as a proportion of all households in Australia. AHURI, using ABS Census data, 1981-2016, CC BY-NC-SA

Social housing (public and community housing) as a proportion of all households in Australia. AHURI, using ABS Census data, 1981-2016, CC BY-NC-SA

Read more: Australia's social housing policy needs stronger leadership and an investment overhaul

More than one in four people who enter social housing use it as a launchpad to more stable employment and market housing. Clearly, then, the sector plays a valuable role in stabilising lives and raising prosperity. These important functions should be safeguarded in the future as pressures on the sector continue to grow.

Overall, one of the things this new work gives us is a long view – hopefully a different view – of the social housing sector and its role over time in Australian lives. It reminds us the impact of social housing is felt well beyond the 4% of the population who may live in it at any one time.

Our social housing infrastructure has certainly been part of the housing experience of many Australians or their parents. We therefore underestimate the effectiveness of social housing as a springboard into home ownership, or a temporary safety net, when we only think of the 4% it currently houses.

Emma Baker, Professor of Housing Research, School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Adelaide; Chris Leishman, Professor of Housing Economics, University of Adelaide, and Rebecca Bentley, Professor of Social Epidemiology, Centre for Health Equity, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.