Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Bruce Bradbury, UNSW Sydney

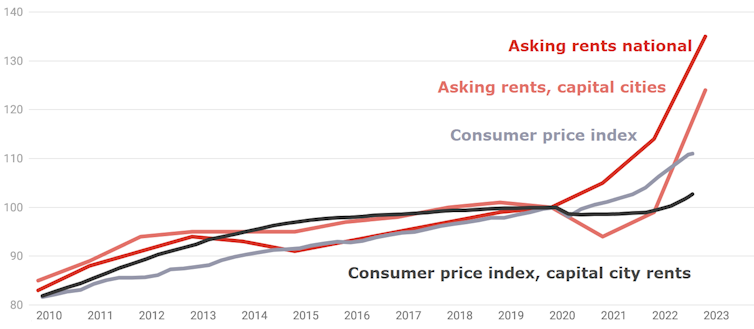

For many Australians, the rent crisis is just starting. Advertised rents have been soaring, but mainly for new rentals – so called “asking rents”.

The broadest measure of rents actually paid – the rents on the 480,000 or so capital city properties the Bureau of Statistics uses to calculate the consumer price index – has climbed only modestly, increasing 3.5% in the year to October.

Rent cuts during the first year of COVID mean the Bureau’s measure of capital city rents is just 2.2% above where it was in February 2020, ahead of the COVID lockdowns.

But advertised rents are climbing steeply. According to property consultants SQM Research, they are an extraordinary 35% higher than in February 2020.

Asking rents versus consumer price index rents

Jan/Feb 2020 = 100. Calculated from SQM Research and ABS CPI

Jan/Feb 2020 = 100. Calculated from SQM Research and ABS CPI

Part of the reason for the difference in the two measures is that rents have been climbing most strongly away from the cities, and the Bureau’s consumer price index only incorporates capital city prices.

But probably more important is that newly-advertised rents are only paid by a small proportion of renters.

Most renters are likely to be paying rents set some time ago when the property was last advertised, or regular increases in accordance with a schedule they have become used to. Landlords tend to save the big increases for new tenants.

Average rents so far slow to move

For capital city tenants in total, real rents (which are rents adjusted for the rate of inflation) remain lower than they were in 2020, and also lower than they were in 2010, because other prices have increased faster.

But the changes in advertised rents suggest substantial increases in overall rents are coming.

When this happens it will place severe pressure on the living standards of the most vulnerable. What can we do about this?

In the long run, the best solution is to provide more dwellings. A wide gamut of policies come into play, from public investment in housing to land use controls to improvements in transport. But they take a long while to work.

More immediately it might help to restrict foreign arrivals, at least for while, but this would hurt Australia’s education and tourism industries.

The simplest short-term response is to financially support renters.

Rent Assistance is in place, but too low

Commonwealth Rent Assistance is already available to Australians on pensions and benefits including JobSeeker, the Family Tax Benefit and Parenting Payment.

But it is only modest. It amounts to 75% of the rent paid between two thresholds, both of which are low compared to actual rents.

For people living alone, the upper threshold is A$169 per week, for a couple with two dependent children it is $250 per week.

The maximum available to a person living alone is $75.80 per week, or about $10 a day. The maximum available to a couple with two dependent children is $89.20 per week – about $13 per day.

The 2021 Census provides an indication of how far the rent thresholds have fallen below rents paid. It found the median rent for a one-bedroom home in Sydney was $451 per week. Only one quarter of such dwellings rented for $379 or less.

In other regions the rents were lower, but still well above assistance thresholds.

Research I conducted with Trish Hill for the Australian Council of Social Service found the $10 per day and $13 per day available to singles and families does go a little way towards closing the large gap between JobSeeker and the poverty line, but there’s ample scope to lift it to something nearer the rents actually paid.

The 2009 Henry Tax Review recommended linking the upper rent threshold to the 25th percentile of actual rents for one and two-bedroom dwellings in capital cities (the rent level that 75% of rentals exceeded).

Rent assistance could double

My calculations suggest the threshold proposed by the Henry Review would now be $354 per week – more than twice the current upper threshold for singles.

If the rest of the payment formula remained unchanged, this would boost the maximum payment 2.8 times to around $215 per week for singles – enough to make a big dent in rent payments. And it would automatically adjust in line with subsequent rent increases.

Would such an increase be simply redirected into landlords’ pockets?

The Henry Review argued that wouldn’t happen much, and to the extent it did, it would encourage more investment.

More assistance shouldn’t push up rents

For people who are at the maximum payment threshold, an increase in rent assistance would be just the same as any other increase in income – it would give them more to spend on a wide array of things rather than only housing.

One way to minimise upward pressure on rents and help those in the highest-rent locations more would be to vary the threshold by region. The Henry review didn’t recommend this, arguing that its recommended maximum rate of payment would be high enough in all locations.

But if any increase offered is not as generous as that proposed by Henry, varying the amount by region could distribute what is offered more fairly.

In time, we will need to offer rent assistance more widely

What I have proposed isn’t perfect. Rent Assistance is generally paid only to Australians on benefits, meaning many vulnerable renters could miss out.

Even though it is available to some families receiving Family Tax Benefit A, the tight rules governing that benefit mean only about 154,000 families on it get rent assistance.

The likely rent increases in the pipeline will create pressure to expand rent assistance to a wider range of families in financial stress.

Bruce Bradbury, Associate Professor, Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney

Image: Getty Images

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.