State Library NSW

State Library NSW

Between the first and second world wars, Australia’s high-end architecture was strongly influenced by exotic scenery from Hollywood’s rapidly accelerating movie industry.

Southern California’s style of seductive glamour and decadent hedonism – recalling the sun-blessed heydays of Roman emperors and Mughal sultans – especially inspired developers and designers of lavish cinemas, mansions, blocks of flats and leisure gardens with swimming pools.

The best of Hollywood

Sydney’s Potts Point peninsula was a crucible of this trend, especially after music publishing mogul Frank Albert hired English architect Neville Hampson to create his splendid residence Boomerang, facing Elizabeth Bay.

In 1924, Hampson and Albert visited Los Angeles to find ideas from “the best of Hollywood”. The pinnacle then was La Cuesta Encantada, a vast hilltop estate that media magnate William Randolph Hearst was developing, in Spanish, Italian and French neo-classical styles, with architect-engineer Julia Morgan.

Their own version of Hearst’s castle included the Baroque cathedral-inspired Casa Grande, three large guest houses and “the most sumptuous swimming pool on Earth”.

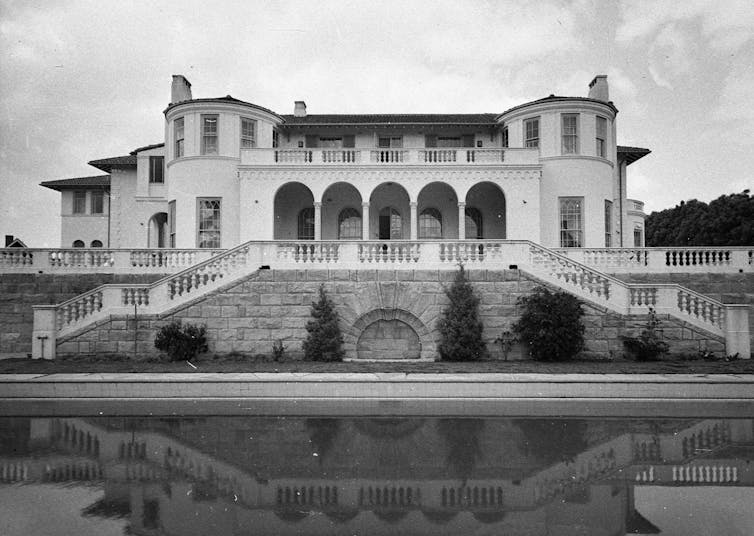

Boomerang, Elizabeth Bay, by architect Neville Hampson. Harold Cazneaux/NLA

Boomerang, Elizabeth Bay, by architect Neville Hampson. Harold Cazneaux/NLA

Hampson and Albert probably also visited Russian actress Alla Nazimova’s Garden of Alla estate in West Hollywood, which was notorious for risqué parties around her swimming pool and lush garden. Her terracotta-roofed mansion exemplified the Spanish-Italian vineyard-villa style that was also being promoted in Australia by architects William Hardy Wilson, Robin Dods, Walter Bagot, Harold Desbrowe-Annear, and Australia’s first dean of architecture, Professor Leslie Wilkinson.

When Wilkinson founded the University of Sydney’s Faculty of Architecture in 1919-20, he strongly criticised the ornamental features and complex roofs typical of the waning Arts and Crafts movement. Instead, he promoted a Mediterranean mode of relaxed, sun-responsive elegance; based on “the work of Spain, of southern Italy, of Provence, with, perhaps, a little of the Orientalism of Northern Africa.”

He also praised Los Angeles updates of west coast Spanish missions, with their adobe walls, arched arcades, timber beam ceilings and rounded terracotta roof tiles, as “a delightful and appropriate style of building”.

This aligned his 1920s Australian clique to the medley of Spanish-Mediterranean styles that were embraced by Hollywood property developers, architects and newly rich stars from the silent films industry.

The Bondi Pavilion by Robertson and Marks. Royal Australian Historical Society

The Bondi Pavilion by Robertson and Marks. Royal Australian Historical Society

The interwar decades

During the interwar decades, many mansions, villas, bungalows and blocks of flats were built in Spanish-Italian renaissance styles, often combined with flat roofs, low proportions and curved corners from the then-new Streamline Moderne movement. Typical features were centre-opening French doors, curved Juliet balconies and columned porticos, colonial-style (multi-pane) windows, loggias and arcades, piazza-inspired courtyards and ceremonial staircases rising around entry foyers.

Outstanding Sydney, examples included Wilkinson’s own villa, Greenway, in Vaucluse; Burnham Thorpe and many other palatial North Shore residences by Frederic Glynn Gilling (with Howard Joseland), and Craigend in Darling Point by Frank Ironstein l’Anson Bloomfield (with Roy Stuart McCulloch).

Two other Hollywood-Mediterranean standouts were The Lodge in Canberra, by Melbourne architects Percy Oakley and Stanley Parkes, and Pine Hill (Bruce Manor) at Frankston, Victoria, by Sydney architects Prevost, Synnot & Rewald (with Robert Bell Hamilton). Both of these cream-painted, terracotta-roofed mansions shared the same first occupants: Prime Minister Stanley Melbourne Bruce and his family.

The Lodge by Melbourne architects Oakley and Parkes. National Library of Australia

The Lodge by Melbourne architects Oakley and Parkes. National Library of Australia

As well as residences, Spanish-Mediterranean styles were adopted for various new types of buildings; especially blocks of flats, petrol stations, car showrooms, hotels and shopping centres, and beach pavilions for new surf lifesaving clubs; notably the Bondi Pavilion by Robertson & Marks.

Spanish aesthetics also suited Catholic schools and churches, such as St Columba’s in South Perth, and crematoria for modern funerals. Two superb cremation complexes were designed by Frank Bloomfield at Sydney’s Rookwood and Northern Suburbs Memorial Gardens.

Cinemas, theatres and opera houses

Australia’s most spectacular interpretations of Mediterranean architecture were the “atmospheric” cinemas designed by Henry Eli White and other antipodean acolytes of John Eberson, America’s leading interwar architect of theatres and opera houses.

Atmospheric interiors tended to feature extravagant ornamentation, scenic trompe l’oeil paintwork and dramatic lighting effects that lent audiences the fantasy of spending a starry night watching performances in the courtyard of Granada’s Alhambra Palace. His over-the-top décor influenced Hollywood scenery styles that seemed sophisticated and exotic in the mid-20th century, but today are often described as “camp” and “kitsch”.

White, a New Zealander, set up his practice in Sydney in 1913 and expanded his career on both sides of the Tasman during the 1920s. Historian Ross Thorne revealed that White worked with Eberson on Sydney’s Capitol and State theatres. He also designed the Palais, Athenaeum and new Princess theatres in Melbourne, the Civic in Newcastle, and Wintergardens at Ipswich, Rockhampton and Townsville.

Foyer of State Theatre, Sydney, by Henry Eli White with John Eberson. State Library of Victoria

Foyer of State Theatre, Sydney, by Henry Eli White with John Eberson. State Library of Victoria

Sydney architects Bohringer, Taylor & Johnson also completed some notable atmospheric cinemas in the late 1920s, including the State (today’s Forum) in Melbourne and the Ambassadors in Perth.

Spanish-Mediterranean architecture was well suited to Australia’s post-Federation culture because it gave a more exotic flavour than the Colonial Georgian revival that accompanied the reigns of kings George V and George VI from 1910 to 1952. And it connected Australia to the exhilarating, glamorous spirit of Hollywood in the roaring twenties.

Now that Australia’s own Hollywood-aligned film culture is prospering, these vintage architectural icons remain alluring.

This is an edited extract from Australian Architecture: A History, by Davina Jackson, published by Allen & Unwin.

Davina Jackson, Honorary Academic, School of Architecture and Planning, University of Kent

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.