Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Matthew Selinske, RMIT University

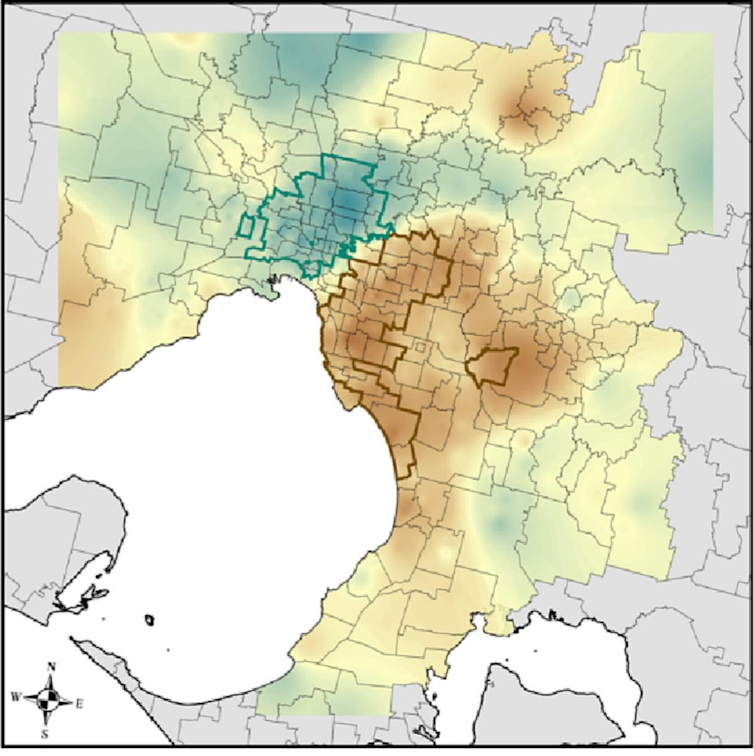

When we were asked to survey people in Melbourne about their relationship with nature, little did we know our findings would reinforce a well-known cultural divide between those living north and south of the Yarra River. Residents of neighbourhoods to the south were overall less connected to nature.

But perhaps a more important finding was that people in Melbourne overwhelmingly supported the creation of more space for nature in the city.

The City of Melbourne commissioned the study and is already applying its findings in programs that aim to foster residents’ connection with nature.

The differences in connection to nature north and south of the Yarra River, with green areas being neighbourhoods with higher average connection to nature and yellow areas having lower average connection. Selinske et al 2023, CC BY

The differences in connection to nature north and south of the Yarra River, with green areas being neighbourhoods with higher average connection to nature and yellow areas having lower average connection. Selinske et al 2023, CC BY

What did the study find?

In our survey of nearly 1,600 residents, commuters and visitors to Melbourne, 86% wanted the city to create more space for nature. Their reasons included:

- to promote mental and physical wellbeing

- to conserve native plants and wildlife in the city

- civic pride

- a belief that if Melbourne could create more nature it would help attract more visitors and help the city’s post-pandemic recovery.

Nearly 75% of respondents had a high connection to nature. More than 75% said they were concerned about climate change and the destruction of nature.

These figures should give heart to anyone promoting greening or conservation actions in the city – the public has your back.

Retirees and university students who had lived most of their lives within the greater Melbourne area had the lowest connection to nature. Despite there generally being more tree cover and beach access south of the Yarra, residents of those areas tend to have a lower connection to nature than those to the north.

City parks with high biodiversity help strengthen people’s connection with nature. Shutterstock

City parks with high biodiversity help strengthen people’s connection with nature. Shutterstock

Why promote people’s connection with nature?

The City of Melbourne commissioned the study as part of its Nature in the City Strategy. Its aim, in part, is to “create a more diverse, connected and resilient natural environment” and “connect people to nature”.

The strategy set this target: “By 2027, more residents, workers and visitors encounter, value and understand nature in the city more than they did in 2017.”

Connection to nature is the extent to which an individual identifies with nature. It stems from a belief that we all have a natural affinity for nature, known as biophilia.

Nature anywhere can offer respite from stresses and be a source of inspiration, creativity and spiritual connection. But individuals have varying levels of connection to nature, which may change during their lifetime.

If you have high level of connection you may feel a real kinship with nature. It’s an important part of your life. People with high connection to nature are more likely to support environmental policies, take part in conservation activities and have higher wellbeing.

Those who feel less connected are less likely to engage with nature. Their wellbeing can suffer as a result.

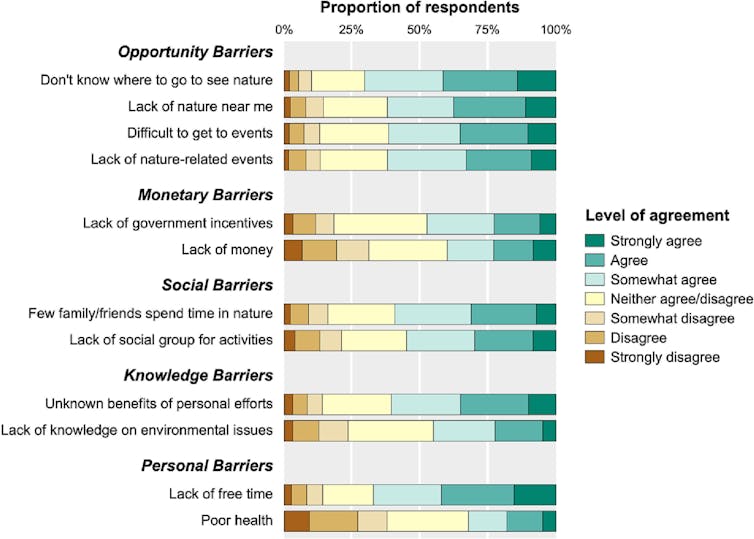

Barriers to engaging with nature as identified from responses to the survey. Selinske et al 2023, CC BY

Barriers to engaging with nature as identified from responses to the survey. Selinske et al 2023, CC BY

Exposure to and engagement with nature are important for our physical and mental health. Studies have shown exposure to natural environments reduces blood pressure and stress levels, and improves cardiovascular health.

Nature also fosters emotional wellbeing. Research has consistently shown spending time in nature reduces anxiety, depression and mental fatigue.

This is especially important for stressed city residents. As well as its health benefits, urban nature has positive impacts on our mood, crime rates, social cohesion and quality of life.

So how do we bring people closer to nature?

The reasons for the north-south divide in residents’ connections to nature aren’t clear and require more research. However, the other findings are already being applied to strategies to help people engage with nature and enjoy the benefits.

Research has shown young people’s connection to nature tends to decline when they reached their mid-teens. While there might be a spike in connection as they reach their 20s, it can plateau by later adulthood.

Young people go through many changes in their lives before adulthood. For many, other activities take priority over spending time in nature. Re-engagement strategies could include more nature-based social events for teens and young adults, to help sustain their connection to nature through to adulthood.

While some retirees had strong knowledge of Australian biodiversity, their low connection to nature could be due to lack of mobility and social connection. One possible way to re-engage this group is to bring nature to them. We could set up more community gardens near them, creating social opportunities as well, or make nature part of their homes.

In response to our findings, the City of Melbourne ran online workshops to identify where retirees engage in nature, how connections with nature are formed, and possible barriers and strategies to strengthen these connections.

New residents of Australia are a really engaged, environmentally conscious group. Finding ways to increase their local biodiversity knowledge may create stronger ties to the Melbourne area and foster emerging conservation allies. The City of Melbourne is planning programs to increase learning opportunities for these residents who identified awareness as a barrier to taking part in conservation activities.

The city council can also make structural changes to increase the time people spend in nature. Biodiverse streetscapes and green buildings can enhance exposure and connection to nature for residents and visitors.

For starters, the council could green streets while reducing traffic by converting parking spaces into gardens and passing Amendment C376 for Sustainable Building Design. This change to the planning scheme will increase green roofs and walls and the number of trees in the city.

Some residents were concerned that development is reducing the amount of nature in Melbourne. Kon Karampelas/Unsplash

Some residents were concerned that development is reducing the amount of nature in Melbourne. Kon Karampelas/Unsplash

Scaling up voluntary programs, such as the City of Melbourne Urban Forest Fund’s Habitat Grants and Gardens for Wildlife Program, will expand community efforts to create places for nature.

As Melbourne recovers from pandemic lockdowns and becomes the most populated urban area in Australia, making more space for nature is vital to maintain and increase the city’s liveability. Most Melburnians would agree.

We all benefit from spending time in nature whether that takes place north or south of the Yarra.

The author acknowledges and thanks Blake Alexander Simmons, Environmental Social Scientist at Tampa Bay Estuary Program, and Lee Harrison, Senior Ecologist at City of Melbourne, co-authors of the peer-reviewed study published in Biological Conservation.

Matthew Selinske, Senior Research Fellow, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.