Thousands of city trees have been lost to development, when we need them more than ever

Climate change is on everyone’s lips this summer. We’ve had bushfires, smoke haze, heatwaves, flooding, mass protests and a National Climate Emergency Summit, all within a few months. The search is on for solutions. Trees often feature prominently when talking about solutions, but our research shows trees are being lost to big developments – about 2,000 within a decade in inner Melbourne.Climate change is on everyone’s lips this summer. We’ve had bushfires, smoke haze, heatwaves, flooding, mass protests and a National Climate Emergency Summit, all within a few months. The search is on for solutions. Trees often feature prominently when talking about solutions, but our research shows trees are being lost to big developments – about 2,000 within a decade in inner Melbourne.

Big development isn’t the only challenge for urban tree cover. During the period covered by our newly published study, the inner city lost a further 8,000 street trees to a variety of causes – vandals, establishment failures of young trees, drought, smaller developments and vehicle damage.

Still, thanks to a program that plants 3,000 trees a year, canopy growth has kept just ahead of losses in the City of Melbourne.

Read more: Our cities need more trees, but some commonly planted ones won't survive climate change

Canopy cover is crucial for keeping urban areas liveable, shading our streets to help us cope with hot weather and to counter the powerful urban heat island effect. Trees can also be a flood-proofing tool.

Trees add beauty and character to our streets, and (so far) they’re not a political wedge issue in the ongoing culture war that is Australian climate policy. In short, they’re a very good idea, at just the right time.

Counting the trees lost to development

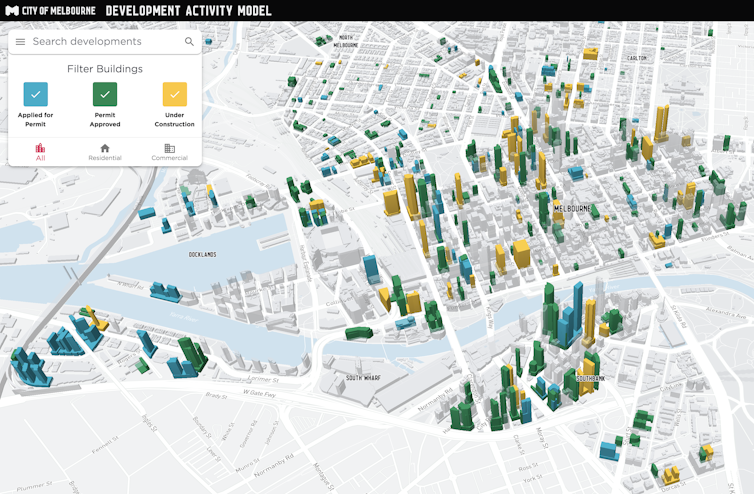

The thing is, this good idea happens in the midst of a construction boom. In Melbourne alone, this includes thousands of new dwellings and billions of dollars of new infrastructure. Many of the new buildings are very large – there’s a handy open database that shows these developments.

Next time you’re walking past a large construction site, look for empty tree pits – the square holes in footpaths where trees have been removed. Maybe you’ve already seen these and wondered what all the construction means for our trees. Well, now we know.

Our study puts a number on the impact of major development on city trees. In the City of Melbourne – that’s just the innermost suburbs and the CBD – major developments cost our streets about 2,000 trees from 2008-2017.

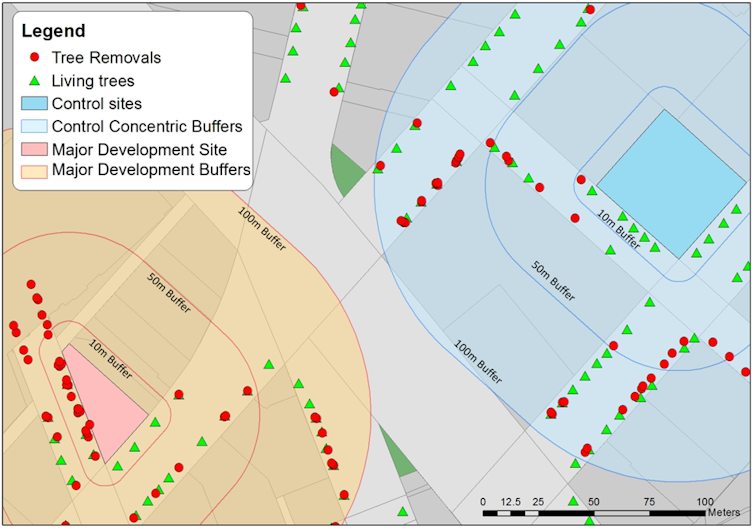

Using council databases and a mapping tool, we tracked removals of trees within ten metres of hundreds of major developments. We found much higher rates of tree removal around major development sites than in control sites that weren’t developed.

Even with the City of Melbourne’s robust tree-protection rules, trees can be removed or damaged due to site access needs, scaffolding, compacted soil, root conflicts with services access, and even the occasional poisoning.

Read more: We're investing heavily in urban greening, so how are our cities doing?

Tree protection limits losses

The silver lining in this story is that the city council’s tree-protection policy seems to be quite effective at saving our bigger trees. The vast majority of removals we saw were of trees with trunks less than 30cm thick. Only one in 20 of the trees lost was a large mature tree over 60cm thick.

This may partly reflect the fact that the council charges developers for not only tree replacement but also the dollar equivalent of lost amenity and ecological values. It gets very expensive to remove a large tree once you factor in all the valuable services it provides. When a tree is a metre thick, costs can exceed $100,000 – and that’s if there are no alternatives to removal.

The protection of bigger trees means Melbourne retained canopy fairly well, despite losing over 2,000 trees. Only 8% of city-wide canopy losses during our study period happened near major development sites. This modest loss is still serious, as removals are having more of an impact on future canopy growth than current cover.

Read more: How tree bonds can help preserve the urban forest

Lessons for our cities

While Melbourne-centric, there are lessons in this study for cities everywhere. Robust policies to protect and retain trees backed up by clear financial incentives are valuable, as even well-resourced councils with strong policy face an uphill battle when development gets intense.

Our findings highlight that retaining and establishing young trees is especially difficult. This is troubling given these are the trees that must deliver the canopy that will in future shelter the streets in which we live and work.

Read more: Keeping the city cool isn't just about tree cover – it calls for a commons-based climate response

Improved investments in how young trees are planted and how long we look after them can help. For example, in a promising local study, researchers showed that trees planted in a way that catches rainwater run-off from roads grow twice as fast, provided planting design avoids waterlogging.

Finally, in the context of rapid development, buildings themselves can play a positive role. Green roofs, green walls and rain gardens are just a few of the ways developments can help our cities deal with both heat and flooding.

There are plenty of precedents overseas. In Berlin, laws requiring building greening have resulted in 4 million square metres of green roof area – three times the area of Melbourne’s Hoddle Grid. In Singapore, developments must include vegetation with leaf area up to four times the development’s site area, using green roofs and walls. Tokyo has required green roofs on new buildings for nearly 20 years.

The solutions are out there, and urban greening is rising in profile. Recent commitments in Melbourne, Canberra and Adelaide are promising. Our study findings are a reminder that, even for the willing, we’ll have to take two steps forward, because there’s inevitably going to be one step back.

Read more: For green cities to become mainstream, we need to learn from local success stories and scale up ![]()

Thami Croeser, Research Officer, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University; Camilo Ordóñez, Research Fellow, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, University of Melbourne, and Rodney van der Ree, Adjunct Associate Professor, School of BioSciences. National Technical Executive - Ecology, WSP Pty Ltd, University of Melbourne

Image: University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles