Vertical schools are increasingly common. This is what students want in ‘high’ school design

The traditional idea of a one-or-two-storey school, spread over a vast campus is no longer an option for some new schools. Population growth and a lack of land in urban areas mean some schools have to go up.

The traditional idea of a one-or-two-storey school, spread over a vast campus is no longer an option for some new schools. Population growth and a lack of land in urban areas mean some schools have to go up.

This has seen vertical schools become increasingly common. These are schools that tend to have more than four storeys.

Some academics argue vertical schools are not well suited to children’s need for space and learning. But what do children want?

I asked students for their opinion

My study published this week surveyed students at three vertical schools. The schools had between five and ten storeys and were in Brisbane and Melbourne. They enrol students from the first year of schooling to Year 12.

I interviewed 38 students in years 3 to 7 through walking tours. They led me around their school, telling me what they liked and didn’t like about their environment.

Children still want space to play

Students told me they wanted access to outside and inside play spaces, even when the weather was bad. They said covered terraces, rooftop gardens and wide hallways allowed students to play in rainy weather.

This is where vertical schools can have an advantage over regular schools. Regular schools often have limited indoor play spaces or their covered outdoor learning areas are easily flooded. As one 9-year-old student said:

We play out here [on the terrace] a lot […] when there’s a wet day […] It’s very good to get fresh air when you’re stuck inside.

While vertical schools generally have limited space on school grounds, they are usually built in central urban locations with parks or green spaces close by. These provided children with access to a variety of outdoor environments within walking distance, an opportunity which is not necessarily available in a suburban school.

They don’t want to spend breaks climbing stairs

Children had to travel via the stairs multiple times a day, for recess or lunch breaks or to change classes.

Students said having to line up to walk up or down the stairs during the peak recess or lunch time wasted their breaks. This was particularly a concern for the primary school participants in years 3 to 5 who found climbing the stairs “tiring” and said it “hurt [their] legs”.

Children tried to limit their use of stairs by using learning and recreational facilities close to their home rooms, if permitted.

Some common facilities in one of the schools were located on intervening floors, a design feature that children described as “really convenient”. As one 12-year-old student said:

You just need to walk up one or two levels […] and you are at where you want to be.

They don’t want too much noise

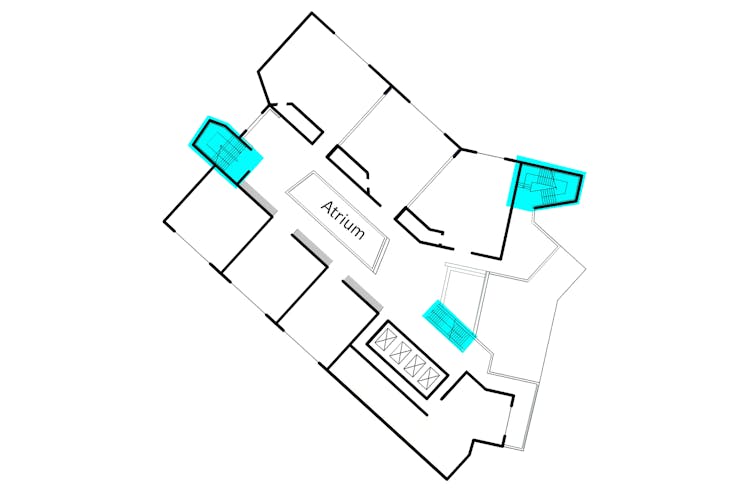

Open-plan classrooms and atrium stairways, where the stairs hug the edges of an atrium, are common features in vertical schools.

Students said they were major sources of noise pollution. They complained “the stomping [on the stairs] could be really loud” and “could interfere with [their] learning”. As one 9-year-old student told me:

if someone drops something on level one, you can hear it from level four.

This particularly happens when the learning areas are open to the atrium and the main staircase and therefore the noise travels between the levels.

Research suggests building stairs in the corners of the building and separating them from the atrium can minimise noise. This way vertical movement won’t interrupt any central learning spaces.

But they want to be able to bump into each other

Children said they wanted ways to meet their friends informally. They did not want to feel closed off in their class groups.

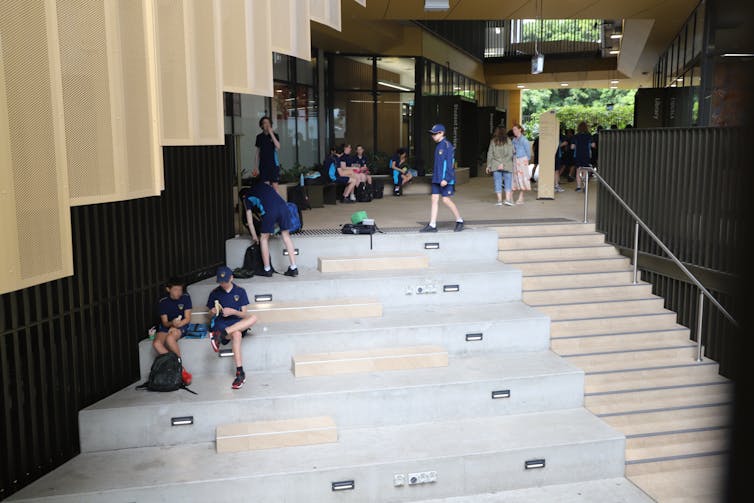

Atriums, wide stairs, and expansive views both inward and outward can promote a sense of community at school. As a 9-year-old student described:

[Kids] can see what’s going on down there and if they see someone, they can knock on the glass and wave. And sometimes kids can watch their friends go to choir on those steps down there and they wave to them.

This type of interaction is important as research shows a sense of community increases children’s emotional attachment to school, resilience and overall sense of wellbeing.

They also want a choice over the use of outdoor spaces

Children would like to choose their preferred outdoor space during breaks, whether they are terraces close to the learning spaces, school grounds or neighbourhood parks. As one 13-year-old student said:

I wish we could sit on [the terraces of] all of the levels […] You’re not allowed to go past level one in your lunch breaks because there is no supervision up here.

While all these opportunities might be present in a vertical school, using them all at the same time poses a challenge to the adult supervision.

Schools struggling with staff shortages may not be able to supervise students in multiple floors and the neighbourhood park during breaks. But this can make spaces overcrowded.

Additionally, vertical movement is strictly programmed in primary schools. Children rely on the teachers taking them upstairs or downstairs before and after the break.

Despite attractive architectural concepts anticipating stair landings for informal interactions, children were unable to pause at their leisure and connect with their environment or each other.

Keep talking to students

Vertical schools provide new opportunities and new challenges for the way students play and learn.

My research shows the importance of including children’s perspectives in the initial stages of school design. While architects may offer innovative visions, they will not be the ones eventually using the spaces they create.![]()

Fatemeh Aminpour, Associate Lecturer, School of Built Environment, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles