Victoria's $5.4bn Big Housing Build: it is big, but the social housing challenge is even bigger

The Victorian government has announced the big social housing investment for which housing advocates, industry groups, academics and social service providers have been clamouring for decades.

The Victorian government has announced the big social housing investment for which housing advocates, industry groups, academics and social service providers have been clamouring for decades.

The A$5.4 billion “Big Housing Build” aims to create over 12,000 homes in four years. Of these, 9,300 will be social housing. The rest will be affordable or market-rate housing. The program will replace 1,100 old public housing units.

Read more: Why the focus of stimulus plans has to be construction that puts social housing first

The headline programs include:

-

$532 million to build on public land, including six “fast start” sites, resulting in 500 social housing homes and 540 affordable and market homes

-

$948 million to spot-purchase homes, projects in progress or ready-to-build dwellings from the private sector, adding 1,600 social housing and 200 affordable homes

-

$1.38 billion for community housing projects to build up to 4,200 homes

-

$2.14 billion for “new opportunities” with private sector and community housing providers, producing up to 5,200 homes.

Up to $1.25 billion will go into regional Victoria, which is welcome.

In addition, $498 million was announced in May to refurbish and build public housing.

Just how big is the Big Housing Build?

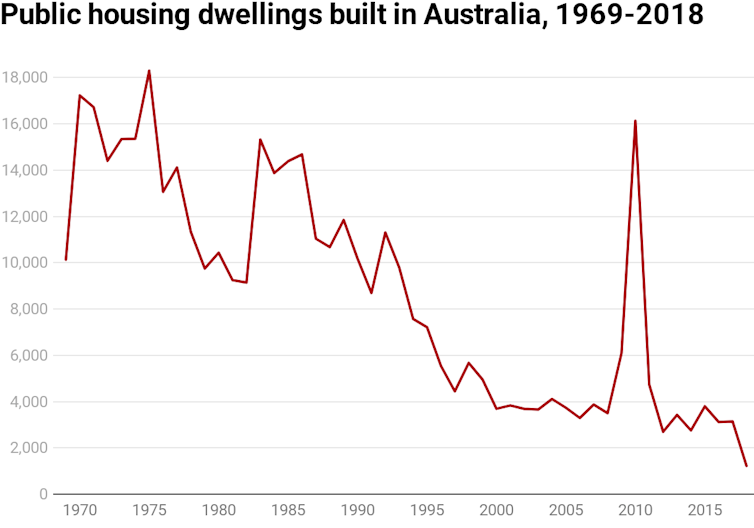

A target of 9,300 new social housing units over four years is definitely “big” by recent Victorian standards. The state’s social housing stock grew by just 12,500 dwellings over the past 15 years – about 830 dwellings a year.

The only comparable investment in Australia in the past two decades was the Commonwealth’s $5.6 billion Social Housing Initiative in 2009. This post-GFC stimulus program built around 19,700 social housing dwellings and repaired 12,000.

Is it enough?

No. It will take a long time and continued commitments of a similar scale to overcome the massive shortages in Victoria and Australia.

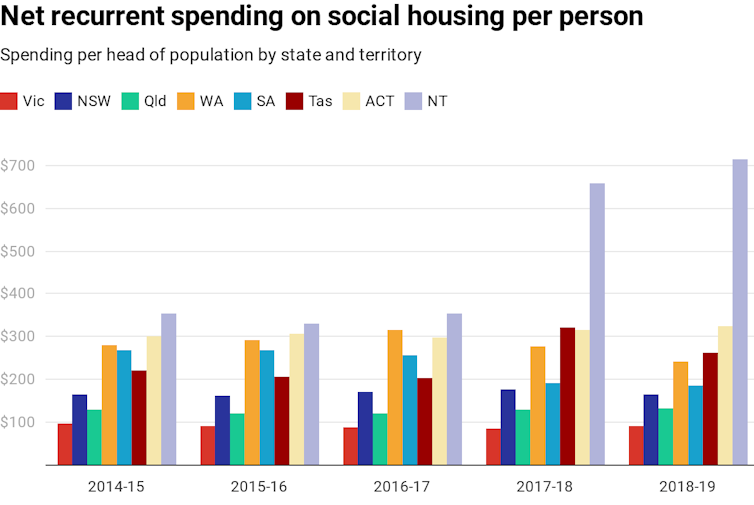

Victoria has a history of spending less on social housing per person than the rest of Australia.

University of Melbourne research estimated a 164,000 shortfall in social and affordable housing in Victoria in 2018. The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute estimated an extra 166,000 social units would be needed by 2036.

Read more: Australia needs to triple its social housing by 2036. This is the best way to do it

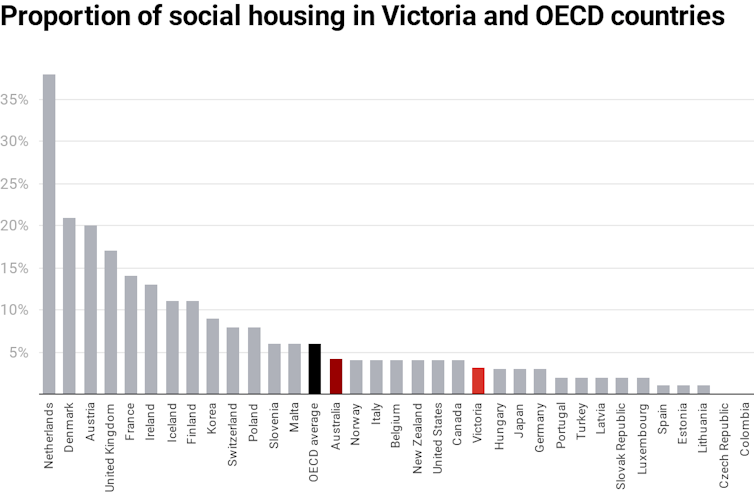

The Big Housing Build aims to increase social housing dwellings in Victoria from 80,500 to about 89,000 – about 3.5% of all housing. That’s still less than the Australian average of 4.2% and the OECD average of 6%.

What the scheme gets right

This program leans heavily on the use of state and local land to reduce the cost of the new housing. My colleagues and I have previously pointed out the large swathes of “lazy” government land across Victoria that could be used for this.

Read more: Put unused and 'lazy' land to work to ease the affordable housing crisis

Offering $1.38 billion in competitive capital grants for community housing providers is also substantially more cost-effective for government than models that rely on private finance and provide an operating subsidy to providers. It appears the entire amount will be spent on supporting construction, rather than on creating a seed fund that drip-feeds investment returns into the not-for-profit sector like the Social Housing Growth Fund does.

Victoria is also joining Canada and the state of California in spot-purchasing homes from the private sector in response to COVID-19. This will deliver social housing quickly. It will also support developers in a depressed market while capitalising on lower prices.

The focus on victim-survivors of domestic violence, Indigenous Australians and people living with mental health conditions is welcome too.

Read more: Why more housing stimulus will be needed to sustain recovery

Remaining concerns

Privatisation of social housing

This announcement continues trends across Australia to shift social housing provision from a state responsibility (public housing) to a more partnership-based model led by community housing providers (community housing).

This approach can leverage substantial contributions from other sectors in the form of land, capital, skills and ideas, producing exemplary outcomes. An example is the Education First Youth Foyer partnership, which is changing how “at risk” young people access housing, education and other services.

However, complex arrangements between multiple partners, especially when using private finance, can be inefficient and costly. Such partnerships are often opportunistic rather than strategic, with priority given to commercial over social outcomes. Community housing residents have less tenancy rights than those in public housing and sometimes pay more of their income on rent.

An emphasis on mixed-tenure developments can lead to cherry-picking of “acceptable” tenants and destroy tightly knit communities. Previous public housing renewal programs based on private sector involvement left a legacy of poorly integrated communities and loss of public land for negligible gains in social housing. We cannot afford to make those mistakes again.

Read more: Social mix in housing? One size doesn't fit all, as new projects show

Lack of a strategic plan

The program comes with a new government agency, Homes Victoria, and the promise of a ten-year policy and funding framework. This level of strategic leadership has been lacking in Victoria and will require bipartisan support. Strong partnerships with local councils will also be needed.

Good policy depends on many elements, including:

- research

- housing targets with geographical and population-group breakdowns

- transparent decision-making

- clearly identified funding streams and responsible agencies

- shared definitions

- monitoring and evaluation mechanisms

- clear time frames

- integration with other policy areas and levels of government.

These elements appear to still be a work in progress for the Big Housing Build. The risk is that this announcement will follow Australia’s pattern of “lumpy” funding and inconsistent policy on social and affordable housing.

Without long-term funding streams, providers find it hard to to scale up, make strategic decisions, invest in internal capacity and plan development pipelines. Without overarching strategy and monitoring, Victoria’s lacklustre history of social housing provision may continue.

Read more: Ten lessons from cities that have risen to the affordable housing challenge

Reduced community engagement

Planning approvals for larger social housing developments will be streamlined. In many cases, the state will take over final decision-making from local government. This will reduce opportunities for community consultation and the state government will need to work hard to ensure high-quality design is integrated into developments.

Where to from here?

As COVID-19 has made clear, everyone needs a home and society benefits from caring for those in need. The speed with which governments moved to house rough sleepers, a seemingly intractable problem before COVID, shows homelessness and severe housing stress can be overcome.

Read more: The need to house everyone has never been clearer. Here's a 2-step strategy to get it done

The Big Housing Build is not perfect and will not solve Victoria’s huge housing challenges on its own. It must be the start of regular cycles of funding to sustain social housing in Victoria. It should also be tied to longitudinal evaluation of outputs and an aligned research agenda to shape best-practice outcomes.

And powers-that-be in Canberra, the list of partners in this program has a large federal-government-shaped gap. When are you going to come to the party?![]()

Katrina Raynor, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Hallmark Research Initiative for Affordable Housing, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles