Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Rachel Goldlust, La Trobe University

Earlier this month, regulators flagged power price rises in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. Like many people, you’re probably wondering how you can minimise the financial pain.

Getting rid of gas and electrifying everything in your home can save you money. Modelling by not-for-profit organisation Renew showed annual bills last year for a seven-star all-electric home with solar power were between 69% (Western Sydney) and 83% (Hobart) cheaper than bills for a three-star home with gas appliances and no solar.

There are other reasons to kick the gas habit, too. As renewables form an ever-growing part of Australia’s energy mix, electrifying the home increasingly helps tackle climate change. What’s more, there are sound health reasons to get rid of gas appliances.

But where do you start? And how do you get the best bang for your buck? Here, I offer a few tips.

Getting rid of gas and electrifying everything in your home can save you money. Shutterstock

Getting rid of gas and electrifying everything in your home can save you money. Shutterstock

A quick guide to home energy use

Australian home energy use can be separated into a few categories:

- space heating and cooling

- water heating

- cooking

- vehicles

- other appliances (many of which are largely already electric).

Of the appliances that typically depend on gas, the largest component (37%) is space heating, followed by hot water (24%) and cooking (6%).

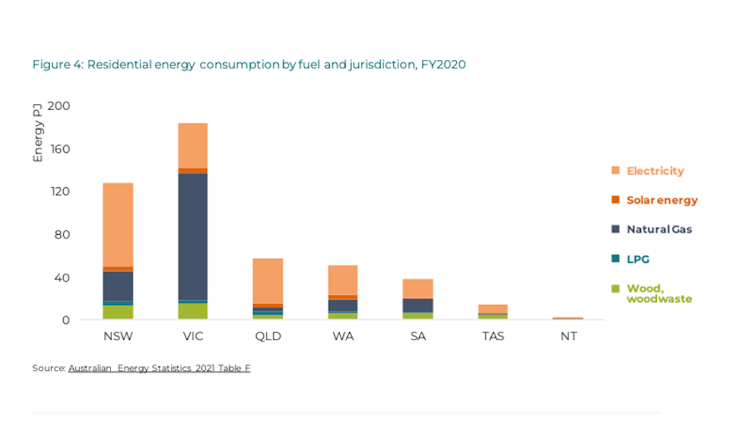

This varies between states. Victoria, for example, is particularly dependent on gas.

But the breakdown above gives some insight into the largest contributors to energy costs in the average Australian home – particularly in the cooler southern regions.

Graph of residential energy consumption by fuel and jurisdiction across Australia 2020. Unlocking the pathway: Why electrification is the key to net zero buildings (December 2022) Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council

Graph of residential energy consumption by fuel and jurisdiction across Australia 2020. Unlocking the pathway: Why electrification is the key to net zero buildings (December 2022) Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council

While both gas and electricity costs are rising, as they are now in most states, all-electric homes can expect lower overall increases. Analysis by Renew has shown ditching the old gas heater in favour of a split system/reverse cycle air-conditioner (without solar panels) can lead to average savings of A$546 each year in Canberra, $440 in Adelaide, $409 in Melbourne and $256 in Perth.

Heating a space with a reverse-cycle air conditioner is about four times more efficient than using natural gas. And when the electricity is generated by renewables, it can be done with zero greenhouse gas emissions.

And what about heating water? Using the existing electricity grid, the cost of using an electric heat pump is around half that of using a natural gas water heater.

The costs fall even lower if a household shifts to solar panels subsidised or financed by government, backed by a home battery providing the energy. In this case, heating costs are around a third of using gas.

Using an electric heat pump is almost half the cost of using a natural gas water heater. Shutterstock

Using an electric heat pump is almost half the cost of using a natural gas water heater. Shutterstock

So what’s the payback?

Buying new appliances costs money. So it’s important to examine the “payback” period - in other words, the length of time it takes for energy bill savings to equal the cost of the initial investment in a new appliance.

The payback period can vary depending on:

- cost and quality of the appliance

- an appliance’s energy rating

- size of the system

- for space heating, whether a split system is replacing an existing ducted system or being added on externally.

A report last year by the Climate Council calculated the approximate cost differences between higher and lower-end electric appliances. Lower-end hot water heat pumps, reverse-cycle air conditioner and induction stoves were priced around $7,818 all together, while higher-end appliances cost around $14,936 together.

Both scenarios included installation costs and $3,000 for electrical upgrades and other costs.

The payback period for low-priced appliances ranged from five years in Hobart and Canberra to 15 years in Perth and Sydney. Higher-priced appliances were in the order of eight to ten years for most cities and 12, 16 and 19 years for Melbourne, Perth and Sydney respectively.

The cost of electrifying the home partly depends on the cost of the appliances you choose. Shutterstock

The cost of electrifying the home partly depends on the cost of the appliances you choose. Shutterstock

Rolled out at scale, household electrification is also a feasible way to reduce gas demand. It may be the only practical option available to decarbonise residential energy.

As research recently suggested, so-called “green” hydrogen – made by using low-carbon electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen – is unlikely to emerge as a cheap replacement for gas boilers. And why look for a technological solution to a problem we already know how to solve?

Modelling by Environment Victoria has shown installing heat pumps for heating and cooling would reduce statewide gas use by 48 petajoules a year, compared to the relatively minimal 0.5 petajoules saved by installing induction cooktops.

At the same scale – and using a similar technology – replacing gas hot water with heat pump hot water reduces household gas use by 10 petajoules each year. That’s an enormous saving of gas.

The bigger picture for all-electric homes

Existing homes can benefit from a combination of electrification, rooftop solar and batteries. They can also benefit from energy efficiency measures such as installing insulation, stopping draughts, closing off rooms and wearing the right clothing for the season.

We can work together to speed up the transition to renewable energy and reduce the demand for gas.

Rachel Goldlust is developing a “Getting Off Gas Toolkit” for Renew. It aims to provide clear, accessible and practical advice to households on replacing gas with renewables. The public is invited to complete a survey to help design the guide.

Rachel Goldlust, Adjunct Research Fellow, School of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.