Why do we have 1 million empty homes?

The recent 2021 Census revealed “one million homes were unoccupied”.Emma Baker, University of Adelaide; Andrew Beer, University of South Australia, and Marcus Blake, University of Canberra

The recent 2021 Census revealed “one million homes were unoccupied”.

This statistic sent housing commentators, government agencies and policymakers into a spin. At a time of significant housing shortages, this extra million homes would surely make a big difference. They could provide housing for some homeless, ease the rental affordability crisis, and get first-home owners into their first home.

There has been a great deal of speculation about how this has happened. Has it been caused by overseas millionaires buying up housing and leaving it as an empty investment? Is it Airbnb taking up homes that could be used for families? Or are cashed-up Gen-Xers double-consuming by living in one house while renovating another?

So, why were 1,043,776 dwellings empty on census night?

In fact, we’ve got a pretty good idea of what’s going on. First, it’s not a new phenomenon. When we compare 2021 with previous censuses, a slightly smaller percentage of our private dwelling stock was classified as unoccupied – just under 10%, compared with nearly 11% at the previous census in 2016.

Since the release of the data, many journalists have pointed to this startling number of empty homes, portraying them as abandoned or left empty. There is almost certainly a much more ordinary and less startling story to tell. We suspect there are three main explanations.

A big part of the story is how the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) determines whether a dwelling is occupied or not. In short, it does its best by using a variety of methods, but, for the majority of dwellings, occupancy “is determined by the returned census form”. If a form was not returned, and the ABS had no further information, the dwelling was often deemed to be unoccupied.

This is important to our interpretation of the empty homes story. At any one time, lots of things are going on in the housing market, and most of it is a long way from abandoned or empty.

For example, 647,000 dwellings were sold in 2021. This means many thousands of dwellings were unoccupied on census night because they were up for sale or awaiting transfer.

The second and perhaps most important contributor to the empty homes story is holiday homes. Estimates vary, but we know 2 million Australians own one or more properties other than their own home. It’s estimated up to 346,581 of these properties may be listed on just one rental platform, Airbnb.

It’s part of the census design to pick a night of the year when the most Australians are at home. If you think back to Tuesday, August 10 2021, it was a Tuesday night in mid-winter, so many of Australia’s holiday homes would have been empty – and counted as unoccupied.

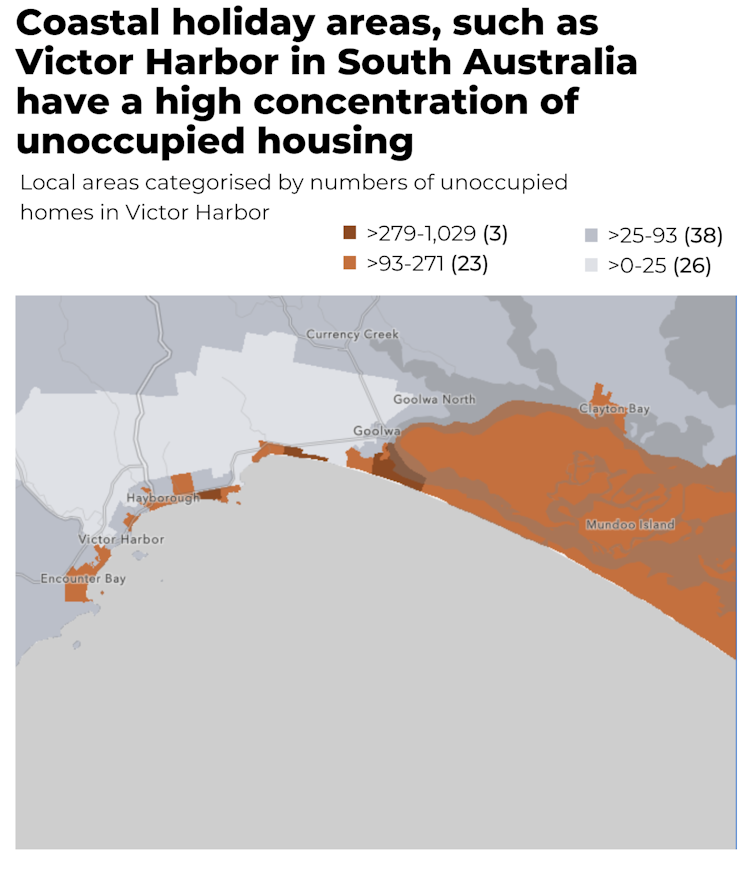

Where are these unoccupied dwellings located?

If we map the distribution of unoccupied dwellings across Australia, two things stand out.

Firstly, unoccupied dwellings tend to be concentrated in sea-change and inner-city holiday spots, such as Victor Harbor in South Australia (as the map below shows) , Lorne in Victoria and Batemans Bay in New South Wales. This reinforces the holiday homes explanation.

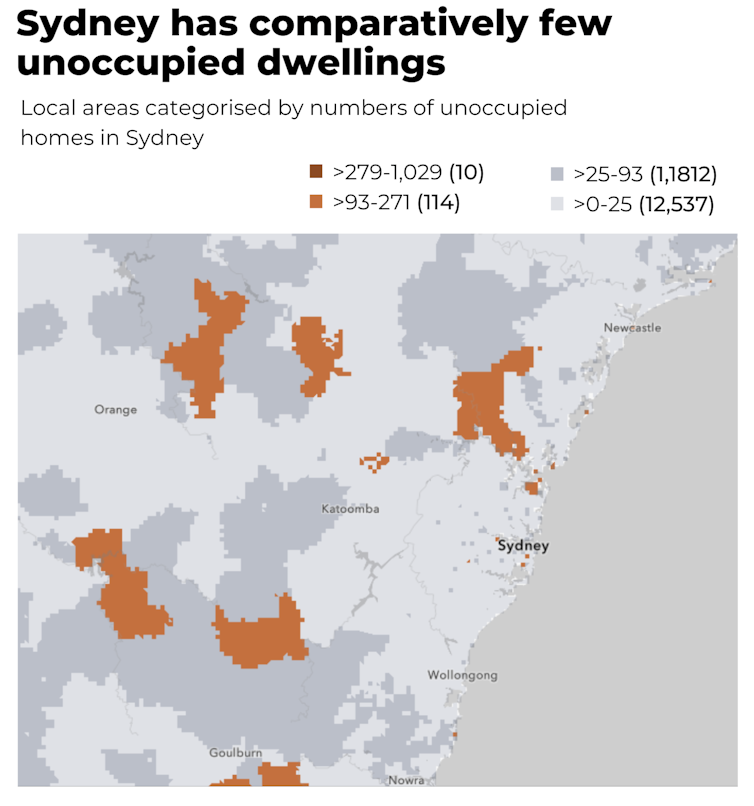

It’s also striking how few unoccupied homes are in our major cities. Sydney is a great example. The map below shows a very uniform absence of unused housing across the whole metropolitan area.

You can use the interactive map below to see how many homes were classified as unoccupied in your local area (click and drag map to your area).

So should we worry about the ‘million unoccupied homes’?

Yes and no. An unknown proportion in that million are not empty, just assumed to be vacant because a census form wasn’t returned. We should regard this as a systematic error in the counting process. No doubt the ABS will be aiming to reduce this in future censuses.

Some of that million are genuinely vacant due to the way the housing market works. This includes, for example, the sales process and the need for vacant possession.

Yet, even if there are substantially fewer than a million vacant dwellings, the reality is that there are too many ways homes in Australia can be left unoccupied for weeks, months, years – and it’s costing all of us. Those who are homeless are paying the highest price. But the rest of us feel the pain through higher rents, increased rates to pay for infrastructure constructed for housing that isn’t occupied, and greater difficulties in getting into the housing market.

We need to find ways to ensure houses are full of people, not left empty as owners wait for investment opportunities to mature, or for absentee owners to go on holiday. We know there are solutions out there. Removing caps on council rates and treating short-term rentals as commercial properties essential to the tourism industry are just two ways we can get better occupancy of our stock. We just need to find the will to implement them.![]()

Emma Baker, Professor of Housing Research, University of Adelaide; Andrew Beer, Executive Dean, UniSA Business, University of South Australia, and Marcus Blake, Senior Data Scientist and Manager, Australian Geospatial Health Laboratory, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: https://www.intelligentinsurance.co.uk/property-usage/unoccupied-home-insurance/

- Popular Articles