7NEWS.com.au

7NEWS.com.au

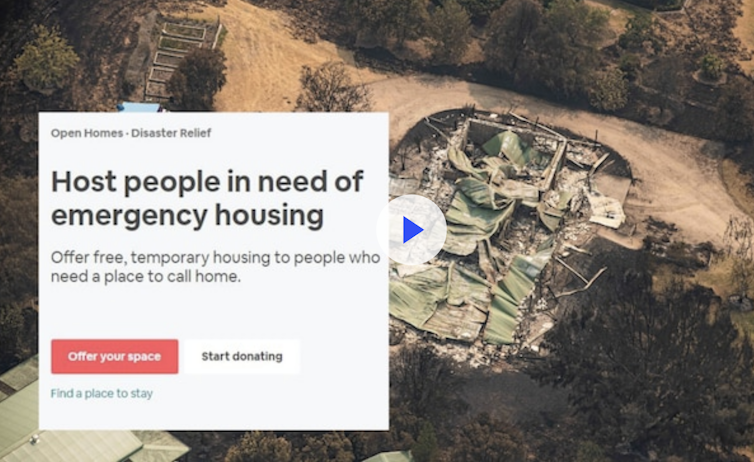

With more than 3,500 homes destroyed by disastrous bushfires, the willingness of government and community to work together to find ways to house people has been heartwarming.

Australians showed great concern for people who were unable to return home. Responses to help find housing while they rebuild their lives and homes, which might take years in some cases, have been fast and innovative.

But what about the many more people who were homeless before the bushfires? On the 2016 Census night, 116,427 were homeless. If the same government and community effort went into helping people who are homeless for reasons other than bushfires, some innovative solutions might be found.

Read more: Homelessness soars in our biggest cities, driven by rising inequality since 2001

The desire to help people who lost their homes to the fires was evident in the breadth of collaboration and range of housing options made available. These ranged from emergency accommodation and rental housing assistance to initiatives such as open homes, spare caravans and vacant holiday houses.

Planning can adapt rapidly in a crisis

Town planning processes, and changes to these processes, are generally slow. However, the acceptance of options outside “typical” planning practice to house bushfire-affected people was impressively fast.

The New South Wales government rapidly eased planning controls. These changes allowed people to stay in a caravan park or camping ground or install a movable dwelling, such as a caravan, on land for up to two years without requiring council approval.

Many councils made large public spaces – such as showgrounds – available as “primitive” camping grounds or emergency evacuation centres. The planning rule amendments gave councils flexibility to modify the usual conditions if necessary to house people who’d lost their homes.

These actions were not controversial or disputed by most because the urgent need to house displaced people was clear.

Government and community involvement in housing bushfire-affected people has been wide-ranging, led to innovative ideas and allowed for rapid changes to approval pathways and planning controls. This “helping people in a crisis” thinking has created an environment of seeking and accepting new housing options.

Read more: 'I didn’t want to be homeless with a baby': young women share their stories of homelessness

Room for innovation in housing the homeless

The number of dwellings available is only one aspect of homelessness. However, increasing affordable housing options would surely help a great many people. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, about 2.1 million adults were classified in 2010 as having been homeless at some time in their lives.

Of course, not all housing options for bushfire-affected people would suit or be relevant to Australians who are homeless. But we can certainly learn from the bushfire examples of innovation in planning to solve a crisis. This sort of thinking across government and community could have impacts on the supply of housing options and on overall rates and perceptions of homelessness.

Read more: Carelessly linking crime to being homeless adds to the harmful stigma

Previously proposed planning options to increase the supply of affordable housing include subsidies and planning bonuses for developments that include affordable housing, as well as mandated targets. However, to ensure success, planning approaches to housing need to be coupled with local community engagement.

Community plays a key role

Community involvement and acceptance are particularly important when we are talking about innovative housing options. Without community support such ideas would likely not be accepted and could lead to conflict.

The Planning Institute of Australia stresses the need for community consultation:

A surer bet would be affordable housing targets developed in consultation with the community … As well as boosting supply, housing targets backed by good design standards would improve the quality of our built environments and help alleviate the twin problems of diminished social capital and growing economic inequality.

Community involvement and local context have been identified as essential elements of successful innovation in planning. Canada provides one example of a successful community-led initiative to reduce homelessness through collaboration between community, agencies and government.

This article does not provide solutions; it highlights what can be achieved if we work together. Many people in need of housing have very limited means. They struggle to meet their housing needs by themselves, incrementally and often informally.

If governments, community members and academics work together to develop policies that match the realities of the crisis of homelessness, then significant innovation in planning is possible. If we accept homelessness and the overall need for affordable housing as a crisis, and are willing to adapt our collective thinking to solve urgent problems – as we have for bushfire-affected communities – then imagine what we could achieve.

Read more: 5,800 defence veterans homeless in Australia – that's more than we thought

Mark Maund, Research Affiliate, School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Newcastle; Kim Maund, Discipline Head – Construction Management, School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Newcastle; SueAnne Ware, Professor and Head of School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Newcastle, and Thayaparan Gajendran, Associate Professor, School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.