We revisited Parramatta’s archaeological past to reveal the deep-time history of the heart of Sydney

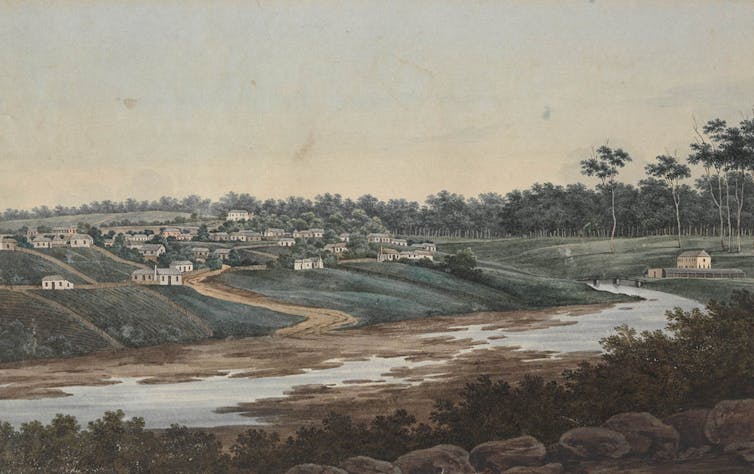

We know quite a lot about the past 200 years of history in Parramatta. Located in Sydney’s geographical centre, on the Parramatta River, it was the first township to be established outside Sydney Cove’s penal colony after the First Fleet arrived at Port Jackson in 1788.

We know quite a lot about the past 200 years of history in Parramatta. Located in Sydney’s geographical centre, on the Parramatta River, it was the first township to be established outside Sydney Cove’s penal colony after the First Fleet arrived at Port Jackson in 1788.

Parramatta became the breadbasket of the early European colony, with land clearing and farming dispossessing the Darug people of the Cumberland Plain. This formed the focus of Aboriginal resistance, culminating in the 1797 Battle of Parramatta led by the great freedom fighter Pemulwuy.

Parramatta’s European history is evident to those who wander through it today — with the remains of old buildings and signs of historical events on almost every corner.

But what about before 1788?

Parramatta has seen intensified development in recent years. High-rise buildings, light rail, road upgrades and landscaping have all impacted the remaining archaeological record of both its deep history and more recent colonial past.

New South Wales’s current state planning laws require each new development to have an archaeological investigation conducted before it proceeds. The aim is to identify archaeological evidence before development starts, and make sure it is managed appropriately.

Where sites are of high cultural or scientific significance, there is an emphasis on protection. Otherwise, the evidence is recorded and recovered before development proceeds. There have been more than 40 such studies in the past 15 or so years.

In our article published today we review these studies to provide a definitive understanding of their results, and reiterate the importance of Parramatta’s culturally significant deep-time history.

14,000 years of Indigenous history

Paramatta’s urban centre has grown upon a more than 3-metre-thick layer of sand. This sand began to be deposited by the Parramatta River 50,000-60,000 years ago as a result of massive floods and other extreme environmental conditions. It continued to be deposited sporadically until about 5,000 years ago.

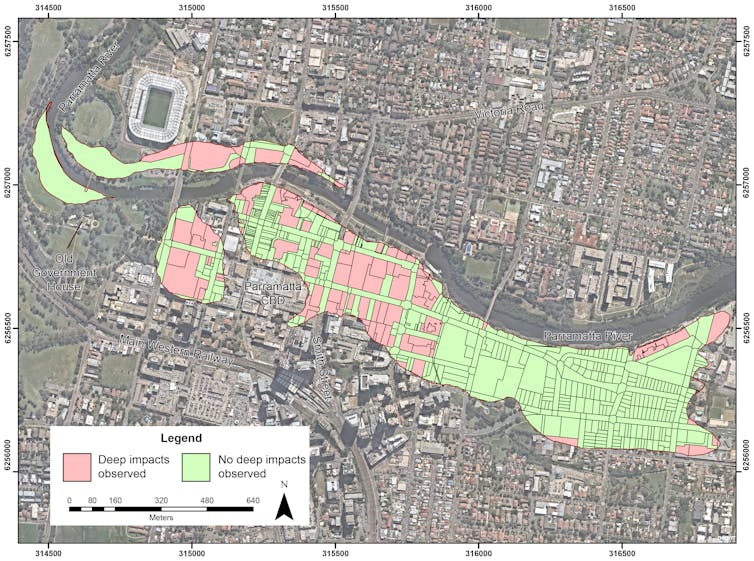

It’s estimated about 800,000 tonnes of sand were deposited across two kilometres of the CBD, where it is still found today. This is all the more impressive when you consider the Parramatta River is fed by only a relatively small catchment upstream.

This sand was blown around during the last Ice Age (or the “Last Glacial Maximum”) between 20,000 and 30,000 years ago. Ultimately this reworking resulted in a sand sheet of about 70 hectares, or roughly 100 football fields. Unfortunately, our study found some 29% of these deposits have been destroyed through development over the past 15 years or so.

This sand body has been in place since the First Nations people arrived on the continent 50,000 (or more) years ago. It retains an amazing archive of evidence that reveals their use of the landscape in deep time, and also records major climatic changes.

Read more: When did Aboriginal people first arrive in Australia?

So far, our earliest evidence for Aboriginal people in the Sydney region is from along the Hawkesbury-Nepean River around 36,000 years ago.

While the Parramatta sand sheet does provide glimmers of evidence for people using it back then, our analyses show they mostly visited this part of the Parramatta River after the Ice Age, which is supported by layers of artefacts in the area dated to this time.

Moving with the tide

Specifically, our paper explores three archaeological projects on the sand sheet at George Street, Hassall and Wigram Streets, and in the grounds of the Bayanami School. All of these sites show increased human use at a time of significant sea-level change.

About 14,000 years ago, the large ice sheets that characterised the glacial period began to melt rapidly. By 9,000 years ago, the sea level in Australia went from 125 metres below current levels to current levels.

This inundation of more than 2 million square kilometres drove people off the continental shelf all around Australia, including from the Sydney Basin. We find fewer sites in Sydney, or indeed the entire southeast corner of Australia, that date to before this sea-level rise.

Read more: Australia's coastal living is at risk from sea level rise, but it's happened before

A previous study of one of these key archaeological sites showed people were highly mobile as a result of this sea-level rise beginning 14,000 years ago. One stone artefact dated to 14,000 years ago was sourced from the Megalong Valley, west of the Blue Mountains, 70km from Parramatta. Most earlier artefacts were sourced from the Hawkesbury River gravels, about 40km away.

Then, over the past 10,000 years, we see a massive increase in local site use and visitation. People used a different stone material for artefacts sourced widely from across the Cumberland Plain (western Sydney), reflecting greater local knowledge of stone resources, longer occupations and likely different trade and exchange networks.

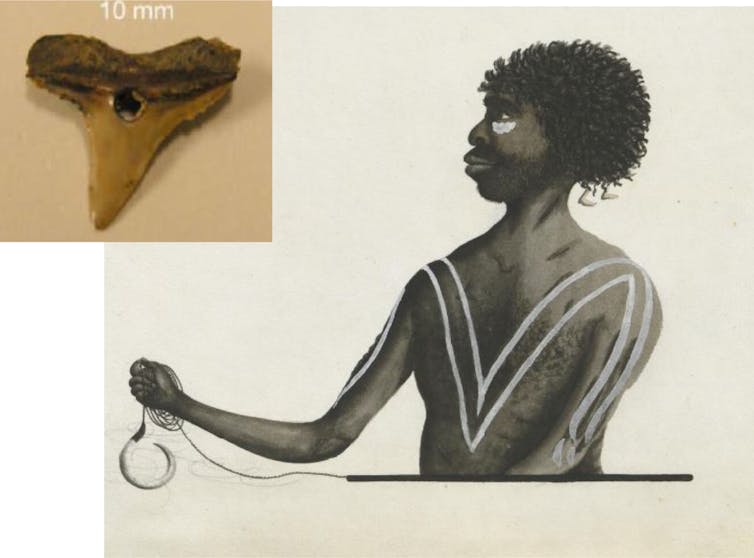

A range of tools have also been found, including grindstones, axe-heads, backed artefacts (such as spear barbs), hearths with heat retainers and heat-treated raw materials — all of which indicate repeated residence over long periods.

Similarly, parts of the sand body with more artefacts also show evidence of camping sites which have retained their structure, demonstrating repeated use. One rare finding at the corner of Charles and George Streets was a pierced shark tooth that was probably used as a hair decoration.

Our analysis fills an important gap in the Indigenous past of one of the oldest townships in Australia. It reinforces the importance of undertaking heritage assessments in areas which are thought to already be “disturbed”.

It also provides a timely reminder these archaeological and cultural landscapes are finite, and are being lost at an unprecedented rate.

Read more: The last ice age tells us why we need to care about a 2℃ change in temperature ![]()

Alan N Williams, Associate Investigator, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, UNSW and Jo McDonald, Director, Centre for Rock Art Research + Management, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles